IR, energy bungling puts brakes on growth

I don’t just mean the inflationary fallout from Covid, which the Treasurer has recently called the “defining challenge of our time”, but policies that have damaged our economy’s ability to cope with change, to be competitive and support economic growth.

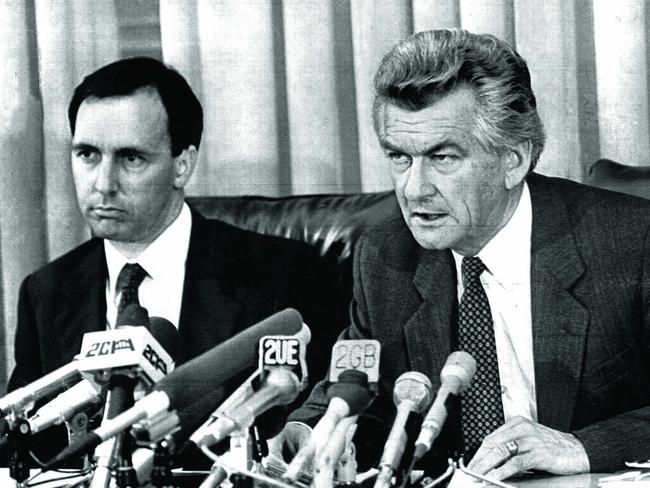

There are two standouts. One is the monumental bungling of the so-called energy transition, in which our governments have contrived to maximise the cost to the nation of reducing emissions. The other is the U-turn on workplace regulation, taking it back towards the sort of centralised regime of pre-Hawke/Keating days.

I cite those two areas because energy and the use of human capital (as economists call it) are so important to economic performance. Historically, this country’s low energy costs partly offset the high self-imposed burdens of our rigid labour market. That’s no longer the case. In fact we’ve brought about the opposite situation. On the one hand, we have been busily eliminating our comparative advantage in energy, while on the other we are reviving our traditional disadvantage with respect to labour. This has helped suppress investment and productivity growth, and taken a toll on real incomes.

If I sound a bit cranky about this it’s because I am. It did not need to happen like this. Governments knew better and in the past have done better.

Take energy. In 1990 the Industry Commission was asked by the Hawke government to conduct a study into the costs and benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as they were called in those days. This was to arm the government with facts and strategies for the Rio Earth Summit. The commission’s public inquiry was a world first, drawing on both scientific and economic expertise.

Its main findings were clear. As a tiny contributor to a global phenomenon, Australia should only act in concert with other countries. Without action by the big emitters such as China and America nothing could be gained. Second, to minimise damage to the economy we should make use of market-based instruments such as taxes and tradeable permits. That’s because in principle these enable emissions to be reduced where the costs of doing it are lowest. (The Greens take exception to this economic logic, as they do to most economic logic. They seem to believe that all businesses should reduce emissions by a comparable amount regardless of cost. Just stating this shows how daft it is.)

These and other findings went over pretty well with both sides of politics at the time, as I recall. So the policy outlook seemed hopeful. How on Earth then did we end up with the costly hotchpotch of measures we’ve got today? How did we get to a situation in which electricity will not only become a luxury but an unreliable one?

What’s worse, we are in a situation where it’s become impossible to openly discuss the best way forward. A policy topic that started in an evidence-based way has become a matter of simple-minded “belief”. Any attempt to use evidence or logic immediately brands you as a “denier”.

In the Ukraine, power stations are destroyed by Russian missiles. In Australia we blow them up ourselves. And we do this without having a way to replace the critical 24/7 service they provide. As Shemara Wikramanayake, chief executive of Macquarie Group, which is heavily invested in renewables, recently told a conference: “You can’t shut up what we have until we have the solutions.” But that’s exactly what’s happening. As if that’s not bad enough, our governments are making it hard for gas to step into the breach – and are dismissing nuclear out of hand.

As for industrial relations, this has been a policy disaster zone for as long as I can remember. The Hawke/Keating era was perhaps the only exception. But John Howard’s rush to take Paul Keating’s reforms to their logical conclusion was ill-prepared and gained little public support – and the reforms were soon reversed.

The truth that is no longer spoken out loud is that WorkChoices actually made economic sense. But of course in freeing up the system, it struck at the very source of union power, provoking a response that contributed to Labor’s election win. Every Coalition leader since then has been gun-shy about IR reform. Scott Morrison made a lame attempt to achieve it by mutual agreement, which failed. He then made a lame attempt to do it without agreement, which barely lasted a week (like his earlier GST reform push when treasurer).

The failures were, as usual, blamed on the Senate. But the real reason in my view was an inability or unwillingness to properly make the case and get the public on board.

Now we have another flurry of IR legislation designed to further boost union power, under the pretext of “getting wages moving” and “job security”. Most of these so-called reforms will only succeed in further undermining the market “dynamism” that Treasury sees as paramount to raising productivity growth.

In the fashion of the times, the legislation that was rushed through parliament was called “secure jobs, higher wages”. I thought at the time a more accurate title would have been “secure unions, fewer jobs”. And this has further to run.

It would be challenging enough if these were our only policy sore thumbs. But they’re not.

We have a tax system that is more about redistribution than growth and looks set to become even more so. Much infrastructure spending seems to be about short-term politics rather than long-term economic benefit. And regulatory obstacles to new projects are becoming almost prohibitive, especially in the resource sector.

We are seeing a return to subsidy programs for favoured industries. This started under the Coalition with a lazy couple of billion of taxpayers’ money, but has been greatly ramped up under this government. History is clear that the main beneficiaries of such public largesse are the private interests best able to curry favour with the government of the day.

While many private sector firms are under the pump, the public sector is flourishing. Employee numbers and salaries went up spectacularly during Covid. It would be great to mark this as a plus for the economy. But government services tend to have low measured productivity and many involve waste – either through poor design or rorting. This has not improved with extra funding. While education spending has gone up, student attainment has gone down. Health spending has continued its upward trajectory, but indicators of performance still languish. Then there’s the fiscal sinkhole called the NDIS, a painful lesson about the “unintended consequences” of policy on the run. Yet the government position seems to be that most public spending is untouchable.

We have entered a new phase in our democracy in which electorates can no longer trust what a political party says it will do or not do in office. This erodes public trust in government and in democracy itself. Moreover, when companies lose confidence in the rules, their propensity to invest, particularly in long-lived projects, is obviously impaired. I never thought the sovereign risk issues prevalent in certain Third World or socialist countries would one day afflict my own.

The Productivity Commission’s five-yearly productivity report is apparently being reviewed by the Treasury as we speak. I think it’s due to be released this month. The Treasurer said it could “kickstart a conversation” about reform with the public. This was good to hear. But it would need to be led by the Treasurer himself, as Keating and Peter Costello did so effectively in the past.

Clearly the government’s redistributive agenda is an ambitious one. But as has been said, a government cannot redistribute what its economy has not produced. Without adequate productivity growth and the income gains this makes possible, the ability to redistribute “other people’s money” must eventually falter.

This is an edited version of comments made by Gary Banks in an interview with Joe Kelly. Banks was chairman of the Productivity Commission from its inception in 1998 until 2013.

The issues that most concern me in thinking about Australia’s need for reform are not the external developments that seem to get most attention, like the prospect of global recession or resurgent protectionism, or even the “climate emergency”, as it is now called. The biggest challenges are ones we’ve created for ourselves.