After all, serious moral argument takes more than hand-waving; it requires articulating a guiding principle and showing why it applies to the situation at hand. If the Yes camp has such a guiding principle, it has never articulated it clearly. There can, however, be no doubt about the moral principle that underpins liberal democracy: it is the principle of political equality. And far from supporting the case for the voice, it contradicts it directly.

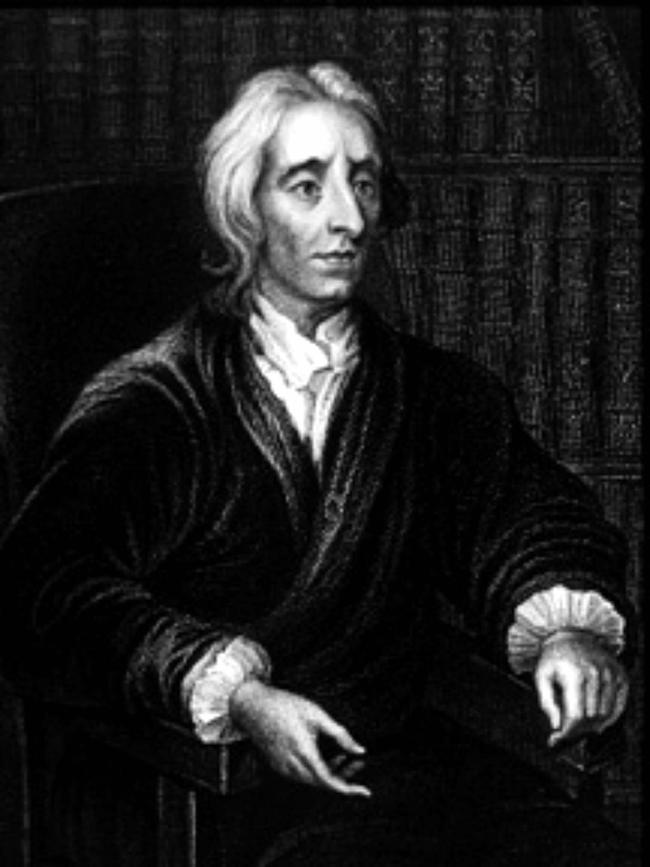

To say that is not to deny that when John Locke asserted, late in the 17th century, that God created human beings in a strict “state of equality”, so that “all power and jurisdiction (must be) reciprocal, no one having more than another”, the moral principle he set out was just an aspiration. But that aspiration has served as the lodestar of Western political development, allowing those who were once excluded to be encompassed within democracy’s ever-broader embrace.

Democracy has, in other words, always had a compelling response to past political inequality: political equality. It does not make the last first; it makes them every bit as good as their fellow citizens.

That is because democracy is an exercise in shaping a shared present and a better future, not in relitigating an unchangeable past. It heeds Thomas Hobbes’ observation, based on the successive invasions that had crashed on England’s shores, that “there is scarcely a commonwealth in the world whose beginnings can in conscience be justified”.

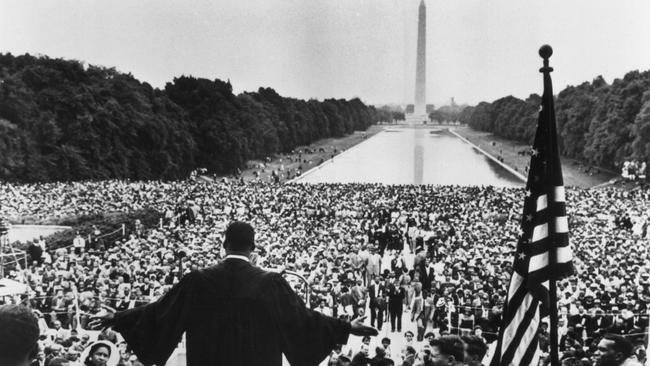

And instead of imprisoning itself in the shadowy world of perpetual victims and perpetual perpetrators, it accepts Martin Luther King’s reminder that “we may all have come in different ships, but we’re in the same boat now”– with our duty being to decide together on its next destination.

There can consequently be no “dictatorship of the proletariat” in democracies: unlike Marxism, we do not pretend to cure past suffering by vesting those whose distant ancestors were wronged with political rights over others. Nor are there, in a liberal democracy, any special citizens who are constitutionally entitled to bellow, any more than there are half or quarter citizens whose voices the Constitution reduces to a whisper.

Indeed, the very idea of differential citizenship is a contradiction in terms, as democratic citizenship has, at least since Aristotle, always meant “the right to the full privileges and burdens of governing the city”, with “every secondary distinction – such as wealth or poverty, beauty or ugliness, wisdom or folly – erased”.

That is not only the essence of equal rights; it is also integral to liberal democracy’s capacity to absorb its inherent tensions.

No system of government creates greater room for diversity; yet it requires enough unity to keep differences within bounds. It wants us to be strongly committed to our goals and values; yet also to accept those the democratic process determines, even when they conflict with our own. And it relies on what the ancients called “civic friendship” – the fellow feeling that makes us willing to help each other out – despite giving rise to enduring, passionately felt conflicts.

Political equality is a crucial part of the glue that makes those contradictions tolerable, assuring this round’s losers they will have a fair chance next time around. In contrast, if there are super-citizens on one side, who are guaranteed a privileged voice in the competition for costly benefits, and mere denizens – who believe they are always footing the bill – on the other, “civic friendship” metastasises into Trump-like fury.

That is why it is impossible to assess the voice without asking what sort of society it entails. The answer is straightforward: it entails a return to ascriptive rights; that is, to political distinctions based on descent.

Ascriptive rights were at the heart of pre-modern societies. In ancient Siam, every person received “dignity marks” – ranging from five for a slave to 100,000 for the heir apparent – by virtue of birth; to know a person’s marks was to know precisely how loud their voice would sound in public affairs.

Liberal democracy was revolutionary because it swept ascription away, recognising every citizen’s equal dignity, regardless of parentage. But if the Yes camp prevails, we will have marks again, with only those who are born into the right category benefiting from a constitutionally enshrined right to be consulted. And to make things worse, the voice founds that distinction on race.

Unpalatable as that is, it might have been acceptable if it genuinely opened the path to reconciliation. But instead of making race less salient, the voice will elevate it into a constitutional divide, reinforcing the impression that Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are fundamentally distinct, biologically separated, permanently opposing camps. It should, in a liberal democracy, be no small thing for the Constitution to effectively require the authorities to register individuals’ race so as to determine their eligibility for public office; to believe that will build bridges, rather than raise walls, is frankly astonishing.

Moreover, the voice’s very design erodes the incentives for the compromise and moderation needed to advance mutual understanding. Thus, the Indigenous professional and managerial class who are likely to dominate it will capture all the benefits of ever-escalating demands without bearing any of their costs; and the louder they shout, the harder they will be to ignore.

At least its predecessors, when they did the cause of reconciliation more harm than good, could be abolished; the voice can’t.

As a result, the most probable outcome, should the Yes camp prevail, is that we will move further along the divisive path that, since the goal of integration was abandoned, has inflicted such dreadful harm.

Describing that path as “different but not separate”, as the voice’s prominent supporters have, is mere cant: it disguises the reality it purports to illuminate.

The fact is that the Indigenous elite is neither separate nor different: it has all the accoutrements of its non-Indigenous counterparts, with the self-righteousness of victimhood to boot. But those whose lives have been blighted by the policies that elite has promoted are both different and separate: separated from the rest of us by poverty, ill-health, violence and early death.

We, as a nation, are responsible for that tragedy – it occurred under our watch, it is a sin of this generation, not of those who came before. And correcting it by ending the separatist policies that have caused it is our foremost moral responsibility.

That is the sole benefit this ill-conceived referendum has wrought. It has forced into the open the question that should have been asked long ago: Are we one country or two? With that question now starkly posed, it won’t be buried again.

The voice, we have repeatedly been told, is a moral question. But throughout this excruciating campaign, the Yes camp has struggled to explain what the moral question is, or why the answer to that question is the voice.