It is consequently unsurprising that even on the budget’s optimistic projections, we will be well into the 2030s before the Commonwealth balances its books.

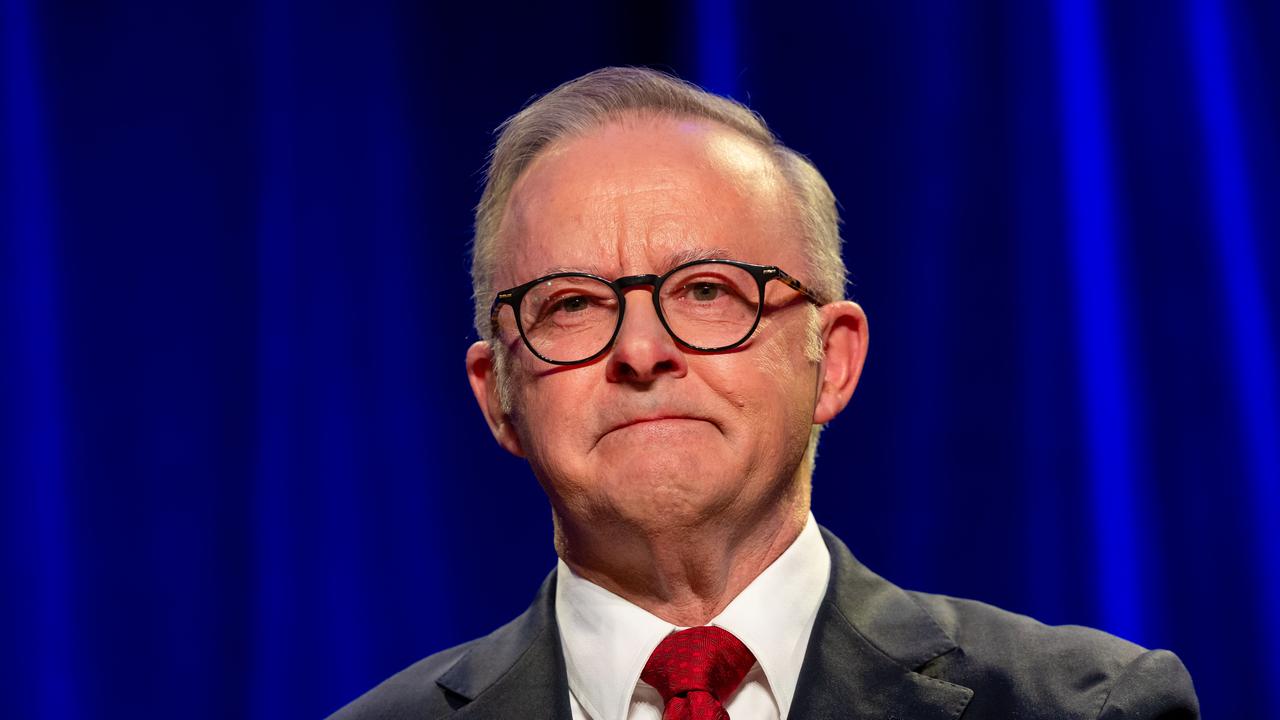

Yet whatever Labor’s anxieties about the forthcoming election, being penalised for fiscal recklessness isn’t among them; it plainly believes that throwing money around is the key to electoral success. The opposition is scarcely better, fearful that promising a speedy return to surplus will raise awkward questions about spending cuts.

Assuming our politicians, for all their shortcomings, can read the public mood, one can only conclude that budgetary restraint is well and truly passé.

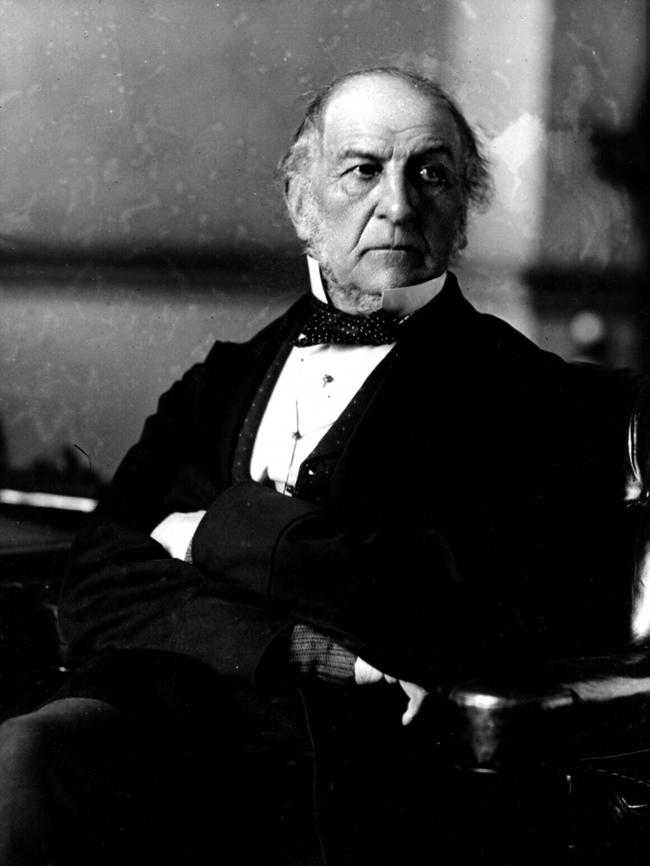

William Gladstone, whose successive periods as chancellor of the exchequer and then prime minister largely shaped modern notions of fiscal rectitude, must be rolling in his grave.

Having entered politics at a time of intense fiscal anxiety – by 1825, the Napoleonic Wars’ astronomic cost had propelled Britain’s public debt to 300 per cent of GDP – durably fixing the public finances was a defining goal of Gladstone’s extraordinarily lengthy career.

The outlook seemed dire. Already in the mid-18th century, when the public debt was barely one-eighth its 1825 level, David Hume predicted that it contained “the seeds of ruin”, as the taxes needed to finance interest payments would eviscerate the middle class, plunging Britain into a “grievous despotism”.

Adam Smith was not as gloomy. However, even he feared that the debt-fuelled “waste and extravagance of government” was displacing productive investment – and the lesson he drew from history was that extensive public borrowing “has gradually enfeebled every state that has adopted it”.

Meanwhile, radicals denounced deficit spending as the pillar of the “old corruption” that enriched the ruling oligarchy at workers’ expense.

Those pressures elicited the beginnings of a response. Particularly important was Edmund Burke’s “Economical Reform” legislation of 1782, which – by curtailing patronage and increasing the transparency of public accounts – started the process of reducing “that corrupt influence which takes away vigour from our arms, wisdom from our councils and every shadow of authority from the most vulnerable parts of our constitution”.

But Gladstone did not merely pursue Burke’s reforms; he elevated fiscal rectitude from being a matter of expediency into the touchstone of public morality.

In 1828, the Select Committee on Public Income and Expenditure had laid down the principle “that no government is justified in taking even the smallest sum of money from the people, unless a case can be clearly established that it will be productive of an essential advantage to them, and of one that cannot be obtained by a smaller sacrifice”.

Gladstone went even further. “All excess in the public expenditure beyond the legitimate wants of the country is not only a waste,” he declared, “but a great political, and above all, a great moral evil” – for it involved an abandonment of the chancellor’s “sacred obligation” as “the trusted steward of the public”, undermining confidence in the integrity of government.

The results of Gladstone’s incessant efforts at fiscal repair were momentous. Government expenditure fell from 15 per cent of GNP in 1830 to 9 per cent in 1880; in France, by contrast, it rose from 7 per cent to 18 per cent. By the period’s end, even GW Norman, a radical liberal, could conclude that the British got “a better return for their moderately just and equal taxes than any other European country”.

But Gladstone was still deeply concerned. “The mischiefs that arise from financial prodigality,” he warned, “creep onwards with a noiseless and stealthy step; they remain unseen and unfelt, until they have reached a magnitude absolutely overwhelming.”

Yet “with every increase of expenditure there grows up what may be termed ‘a spirit of expenditure’, a desire which, insensibly and unconsciously, affects the spirit of the people, of parliament, and perhaps even of those whose duty it is to submit the estimates to parliament”.

How was the “spirit of expenditure” to be exorcised? It was, in part, a question of leadership: of ensuring that no one became (or remained) chancellor who “makes popularity either his first consideration, or any consideration at all, in administering the public purse”.

Forgoing all self-promotion, the chancellor had to, by his “magisterial influence”, infuse the sense of economy into the entire public service, going from the mightiest “permanent officers that bear unobtrusive but effective sway in Whitehall” down to the lowliest “distributors of stamps”.

And it was also the chancellor’s task to constantly explain how and why the country’s finances, and the difficult choices they inevitably involved, were “at the root of English liberty”. Hence Gladstone’s magnificent speeches that, said a contemporary, “made thousands eager to follow the public balance-sheet, and the whole nation his audience”.

It is, however, questionable whether Gladstone could have been so successful, electorally and politically, had his values, shaped by evangelical Protestantism, not faithfully mirrored the broader population’s. At a time when, even in London, that den of sin and inequity, a third of adults were regular churchgoers, those values embodied the archetypal Victorian virtues: not least thrift, which was actively promoted by the ubiquitous Penny Banks that disseminated a culture of “making a choice” for “responsible saving”.

Little wonder then that Gladstone, who adamantly opposed tax concessions, made an exception for savings, which were taxed far more lightly than other forms of income.

And little wonder too that he regarded establishing the immensely popular Post Office Savings Bank, which Karl Marx denounced as “a golden chain on which the government holds a large part of the working class”, as one of his three most important legislative achievements.

The Victorian virtues on which Gladstonian fiscal rectitude so heavily rested are now a thing of the past, replaced by the “virtue signalling” that is nothing more than a form of narcissism. Our leaders may not be up to the task; but is it unfair to suggest that, in the end, each epoch gets the fiscal leadership its moral calibre deserves?

The great economist Joseph Schumpeter, who learned that lesson the hard way when he served as Austria’s finance minister immediately after the First World War, put it best.

“The spirit of a people,” he wrote, “its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare – all this and more is written in its fiscal history, stripped of all phrases. He who knows how to listen to its message here discerns the thunder of world history more clearly than anywhere else.”

It would be a pity if, on May 3, when Australians head to the polls, the only thunder was the catastrophic crash of a nation that has lost its way.

Since coming to office, the Albanese government has increased public spending by over $130bn dollars in a splurge rivalled only by the ill-fated government of Gough Whitlam. And the sheer scale of this pharaonic achievement is understated because it excludes both $45bn in “off budget” spending and the spending promises that will be made in the weeks ahead.