Funding model for voice vote will affect result

The choice is important because it may have a major impact on the result. The government will no doubt weigh up the need for a fair poll while doing everything it can to make a majority Yes vote more likely.

Australia’s last referendum was in 1999 on a republic and new preamble to the Constitution. Prime minister John Howard broke with past practice by establishing taxpayer-funded campaigns. The Yes and No cases each received $7.5m and were prohibited from accepting donations or raising other funds. The government also provided oversight of the advertising materials produced by each side.

The 1999 referendum was also innovative because the government funded independent, non-partisan information for the community about the proposals and Australia’s system of government. The “neutral” campaign received $4.5m in public funding that was spent on information prepared by a panel of five eminent Australians, chaired by former governor-general and High Court judge Sir Ninian Stephen.

Some people assume Australia’s next referendum will be fought along the same lines. However, the default position is that there will not be official Yes and No cases. The rules laid down in 1999 were a temporary measure authorised by parliament only for that referendum. After the poll, the law reverted to provide that the commonwealth cannot spend money on the “presentation of the argument in favour of, or the argument against” a referendum proposal. There are a few exceptions, including that voters can be sent a hard-copy Yes and No case pamphlet.

The last time Labor contemplated a referendum was in 2013 on recognising local government in the Constitution. That experience demonstrates the perils of establishing unequal taxpayer-funded campaigns.

Parliament agreed to temporarily suspend limits on commonwealth expenditure, with the Gillard government allocating $10.5m for the contest. It divided this by giving $10m to the Australian Local Government Association and $500,000 to the opponents of change.

The government justified the uneven split on the basis that the allocation was in proportion to the votes cast in parliament. Hence, 95 per cent of the funding went to the Yes case because that was the percentage of members of parliament who supported the change. The government’s approach provoked an immediate outcry and galvanised opposition against its proposal. Even Coalition members who supported the reform described the funding as unfair and undemocratic. The government had succeeded in loading up financial support for the Yes case, but at the cost of the referendum itself, which was never put to the people.

Key members of the Albanese government will no doubt remember the 2013 experience. They will not repeat the same mistakes for the voice referendum. They will look for other ways to fund the referendum that will maintain community and cross-party support while providing the best chance of success for the Yes case.

A hard-headed assessment suggests the government will not adopt the same approach as Howard in 1999 by setting up taxpayer-funded campaigns. A free-for-all without government support will advantage whichever side has the greatest fundraising potential.

This is likely to be the Yes case with its more established, better organised presence and deep connections into corporate Australia and the broader community.

Equal government funding for each campaign may actually disadvantage the Yes case by providing the No case with money it would not otherwise be able to raise.

The recent federal budget made no provision for formal Yes and No cases. Instead, the Australian Electoral Commission was allocated $50.2m to prepare for the vote and a further $16.1m to increase enrolment by Indigenous Australians. The National Indigenous Australians Agency, which supports working groups that advise the government on the referendum (including a Constitutional Expert Group of which I am a member), received $6.5m.

Another significant measure was granting tax-deductible status to Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition, which will feature heavily in the Yes campaign.

This may be as far as the government will financially support the Yes case. It means the government can leave the funding rules as they are, while still putting in place support to develop a robust model informed by Indigenous leaders, the broader community and constitutional experts. This also provides for a referendum campaign that will naturally advantage the Yes case with its greater fundraising potential.

There are no guarantees this will lead to a successful referendum, but the government may have rightly calculated that this is the best ground on which to fight the campaign.

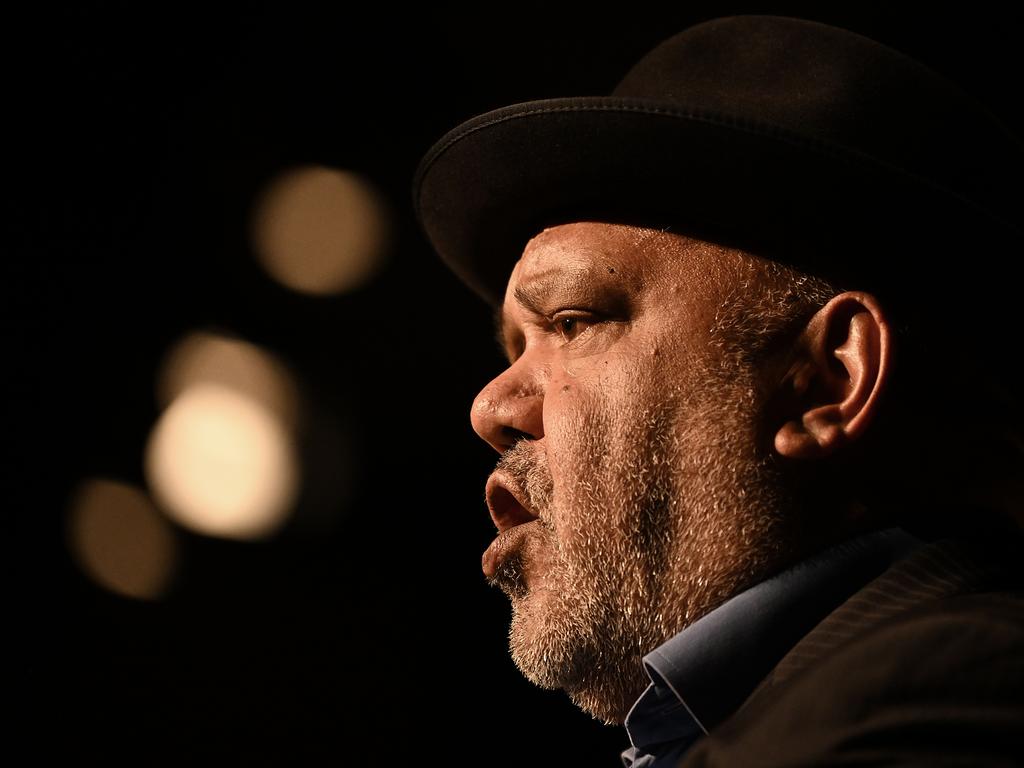

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.

The Albanese government must make an important strategic decision on how to fund the voice referendum. One option is to let the Yes and No cases pay their own way without government support. An alternative is to establish official Yes and No campaigns, along with funding for neutral community information.