That’s limited to the politicians because it’s the elected government that’s ultimately responsible for decision-making, as public servants sometimes need reminding.

Of course, Abbott hardly needed to be told. And his public servants were never in any doubt that he was prepared to take tough decisions. Operation Sovereign Borders, for instance, went ahead despite the scepticism of senior officials within the NSC, including a warning from one that it could cause conflict with Indonesia.

Whether it was flying air force planes through Beijing’s spurious air defence identification zones, mobilising air and sea assets to search for Malaysia Airlines flight MH370, air-dropping supplies to besieged Yazidis on Mt Sinjar, running guns into Erbil, sending special forces to Iraq, bombing Islamic State or preparedness to deploy troops into Ukraine to recover our dead from Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 when the Russians were uncooperative, there was no doubt who was in charge of national security in those days and that the country was in safe and secure hands.

But who is in charge now? The heads of domestic spy agency ASIO and foreign spy agency the Australian Secret Intelligence Servicehave been routine attendees at the national security committee of the cabinet since it was first formed in the Howard era. Not members, because only cabinet ministers (normally the Prime Minister, Treasurer, defence and foreign affairs ministers, Attorney-General plus the Deputy Prime Minister) are formally part of cabinet committees; but the spy chiefs were routine participants, encouraged to add their expertise to everything under consideration and, critically, add to the contestability and frank debate in this most important of rooms.

But no longer.

Instead the Prime Minister reportedly has added the Climate Change Minister as a permanent member and the secretary of that department as a permanent participant, as if it’s temperature rise that constitutes our greatest national security threat.

The exclusion of the spy heads when the strategic outlook is more fraught than it has been in decades, coupled with the ASIO chief saying foreign interference is certain and the risk of an Islamist terror attack in Australia over the next 12 months is realistic, is an unsettling sign that the Albanese government is not entirely serious about national security. Indeed, it’s chilling, former deputy prime minister John Anderson said when I asked him for his reaction on Tuesday night.

But it would be a mistake to see the downgrading of our intelligence chiefs as an out-of-character aberration. There is no doubt the Albanese government started well, but lately there has been little to improve our national security and much to weaken it.

The government put off a decision on the navy’s surface fleet for well over a year, then decided to weaken it in the short term by prematurely retiring at least one of the existing Anzac-class frigates and to hold a further evaluation into additional light frigates with no timeline for acquisition.

When the US requested a frigate to protect shipping in the Red Sea, the government refused, citing responsibilities nearer home, even though the navy previously had kept a frigate or a destroyer almost continuously deployed in the Middle East for the past two decades. When the Ukrainians wanted the Hawkei light armoured car, the government also refused, citing a fault with the brake light, as if that would worry a country fighting for its life. When the Ukrainians wanted our retiring Taipan medium helicopters for use in med-evacuations, the government again refused, also citing safety issues, even though the same aircraft is still widely in use in Europe.

Before Christmas, the government even failed to meet a Ukrainian request for coal to sustain its electricity supply, presumably from climate concerns. (See what I mean about Chris Bowen sitting in NSC but ASIO outside it?)

It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that one reason for excluding the spy chiefs is that the intelligence community, to a man and a woman, is only too well aware we are in a new cold war with Beijing.

But it’s not just China policy that will suffer. Perhaps the government’s failure to anticipate recent boat arrivals and inability to secure third-country repatriation (hence the release of 149 foreign criminals) owes something to the spy chiefs’ absence, given their regional expertise. Although I concede that doesn’t explain the government’s ongoing border protection and detainee crisis, the origin of this calamity better explained by the sheer incompetence of ministers rather than the absence of officials in the NSC.

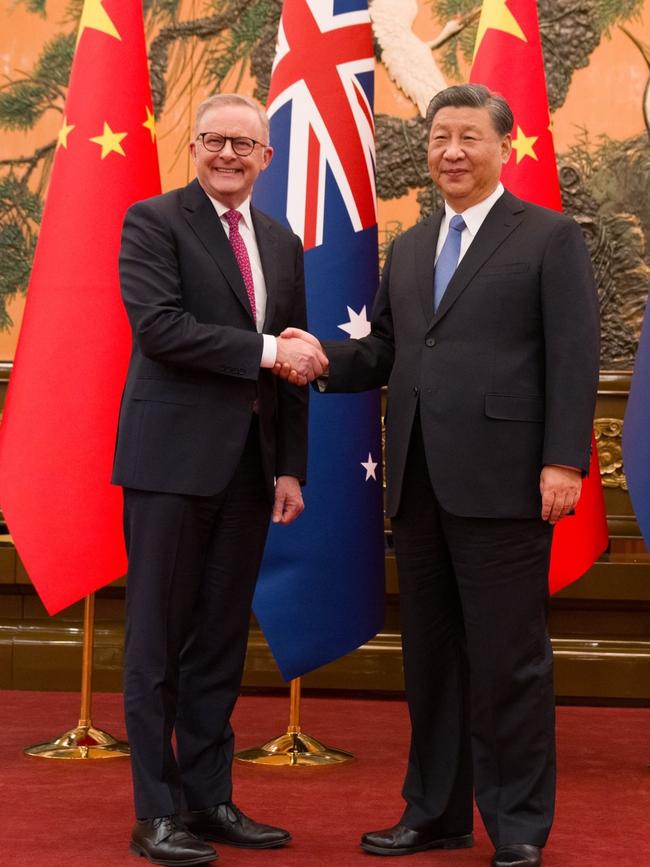

As has become clear in recent months, increasingly the government’s foreign policy is to kowtow to the red emperor. Shortly before the Prime Minister’s trip to Beijing last year, the government announced there’d be no action to take back ownership of the Port of Darwin from a Chinese company despite Anthony Albanese’s pre-election railing over it. And shortly before the Chinese Foreign Minister’s visit here, the government withdrew the anti-dumping action against Chinese wind turbines sold into our market at below cost, increasing our economic dependence.

Yet for all this latter-day appeasement, our wine and lobster exports are still largely blocked, a trumped-up death sentence was still pronounced against a Chinese-Australian citizen, and regime mouthpiece Global Times’ description of our Prime Minister as a “handsome boy” could hardly have been a more patronising put-down. Perhaps the most telling indication of our strategic grovel has been the muted protest against China’s use of sonar to harm our sailors and release of chaff to interfere with one of our planes.

One of the 14 demands publicly made of us by the Chinese ambassador in November 2020 – essentially to allow all Chinese migration and investment, to cease all criticism of the Chinese government, and to leave the US alliance – was to dismantle “anti-Chinese” think tanks.

The government’s review into the Australian Strategic Policy Institute looks like a prelude at least to its emasculation. Beijing would like us to be a strategically neutered, economic client state. For selfish or for ideological reasons, too many leading Australians – business and political elites – seem all to ready to sell out to the neighbourhood bully.

As the Ukraine war reminded us, tension can become hostilities very quickly. Especially if Vladimir Putin wins there, and the Middle East slides into ever great chaos, the likelihood grows of Chinese adventurism across the Taiwan Strait. Are we ready for it; are we even thinking about it; how would we even know when our intelligence chiefs are reduced to listening through keyholes?

The best public servant of his generation, former secretary of the departments of Defence and Foreign Affairs, former head of ASIO and ambassador to Washington, Dennis Richardson once gave Tony Abbott some salutary advice: every so often, he said, you need to kick the public servants out of the national security committee so the officials never forget they are only guests in the room, not members of the NSC.