Enrolment levy will only hurt academics, students and society

The grisly truth, apparently, is that the “Gang of Eight” universities will just milk students dry. But there is not a skerrick of evidence to support these wild allegations.

This view has been spearheaded by a proposed tax on international student enrolments as a component of the Universities Accord. A panel, including academics with careers in smaller universities, has come up with this proposal. But it has a major problem: it tithes Australia’s most productive universities to cross-subsidise other universities. The baseline proposal is a self-serving wealth redistribution and is a tithe on academics’ labour.

The tithe has its proponents. Greg Craven – ever the fan of an evidence-free diatribe – has set his sights on high-performing universities, promulgating emotive discursions. But, as people such as Craven should know, emotional vitriol is not an argument.

In his pieces Craven employs the same style of insult as he and other supporters of the Indigenous voice used to disastrous effect during the referendum – elite universities are a combination of greed and stupidity, combining the attributes of Al Capone and Alan Bond.

In this case we have value-laden catchcries that the top universities are greedy or operate like a cattle market. But these emotionally manipulative assertions are hollow, vapid and disingenuous.

Craven is not alone. Bruce Chapman asserts that “social welfare and economics tell us that the case is incontestable”. Quite why it is incontestable is not clear. Usually when someone says their argument is incontestable without telling you why, it is important to start asking questions.

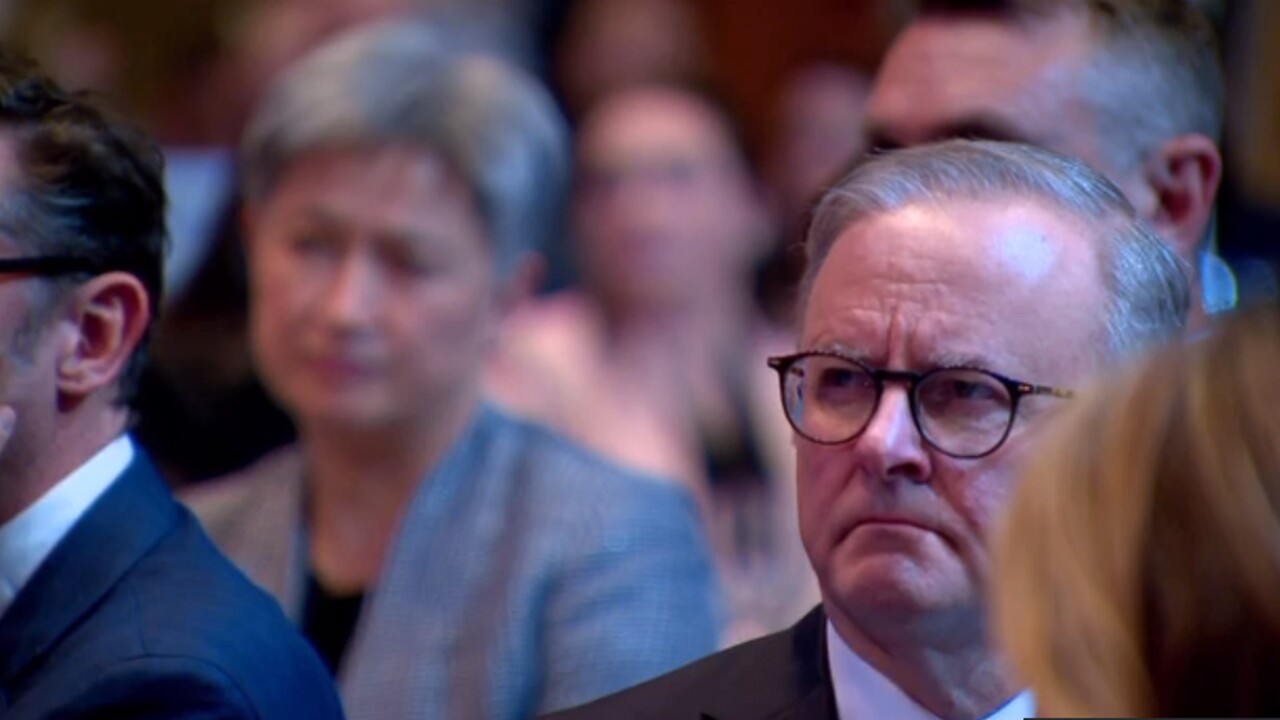

Chapman argues the tax would not deter international students because it will be moderate, at least initially, and students are not sensitive to price. This may be news to the students who are struggling with indexed HECS debt. As Anthony Albanese learned, simply saying something is modest doesn’t make it so.

It is not surprising that Craven – a former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University – would support such a levy: the ACU would benefit from it.

In addition to being a corrupt penalty for attracting students, the levy is based on several faulty premises. First, the most productive universities can afford such a levy. Second, that international students are harmful, especially to local students. And third, geography and history unfairly advantage well-located and older universities.

Let’s start with the first premise: can universities afford a levy? The clear answer is no. Universities are not-for-profit. They do not pay dividends to shareholders or distribute cash. They reinvest cash in education. Thus, the money productive universities obtain from international students directly subsidises local students as well as research.

We also must address the false claim that international students take places from local students. They do not. Academics teach both groups. If another class is necessary to teach international students, universities will run it. Indeed, international students enable universities to offer more resources, facilities and knowledge to local students.

The universities that attract international students do so because of their dedication and hard work across many years, not, as alleged, because of geography and history.

The levy amounts to a tax on having the business sense to choose a good location and the skill to enable a company to survive. It is also disingenuous.

The University of NSW was founded in 1949 but would be levied just as severely as the University of Sydney, which was founded 100 years earlier in 1850. By Chapman’s logic, the long-lived BHP should face a higher tax rate than the highly profitable upstart Google. The also-rans always have something else to blame.

The ultimate impact of such a levy is that it will harm both academics and society. Universities cannot raise fees in an internationally competitive market. Chapman is right on that matter: fees will not increase much. But then universities must internalise the cost of that levy.

Ultimately, given that universities do not generate a profit, this means academic salaries will fall, as will the competitiveness of Australia’s universities with a decline in international rankings and a concomitant fall in revenue from one of our most successful export earners.

In the tradition of the famous Magic Pudding, according to Chapman, a levy on Group of Eight universities will make all universities better off. Congratulations, Bruce, on establishing a new quite revolutionary taxation principle – the Go8 losers facing a billion-dollar tax are winners. Bruce, you have many supporters in the form of HECS liability “winners” out there.

The levy’s proponents must tell hardworking academics at Go8 universities why they should be penalised for the additional effort put into teaching and attracting students relative to where, say, Craven was vice-chancellor.

The net result of the levy is that it would harm productivity. How do we expect workers to respond when they are effectively demonised by people who tell already overworked employees to work ever more but for less money?

University funding is a challenging issue. But redistributing money from the elite top-performing universities is not the solution. It is a penalty for strong performance and harms competitiveness.

The baseline proposal of a levy on international students is an attack on exceptional effort and ought to be discarded along with all such shallow concoctions of insults masquerading as arguments.

Peter Swan AO is a professor and Mark Humphery-Jenner is an associate professor in the University of NSW business school.

University funding has become a vexed issue. There is a lot of noise in this space, with accusations that universities are greedy, anti-social rack renters.