Universities should pay levy on ‘foreign student industry’

The data on international students enrolled in Australian universities is startling. In 2023 there are more than 360,000, generating around $10bn a year – around 25 per cent of the sector’s total budget and, for the most established institutions, this proportion can be as high as 40 per cent. Without these funds the system would be in dire straits.

This topic requires modesty given that economics does not deal easily with the quixotic complexities associated with institutions that are both public and free-market. We will have a go at putting some basic economic thinking into this space, concluding that the levy has a strong basis.

As background we have to introduce two critical concepts: the extent and longevity of taxpayer assistance (subsidies) to our elite institutions; and the “price elasticity of demand” for the international student market.

On the first, here is some data: the age of the top five (in terms of numbers of international students) Australian public universities is 119 years, compared with the bottom five, which is 41 years. This means the former have enjoyed about 80 extra years on average of major taxpayer support. This results in something unsurprising: these universities have the best research reputations and thus the greatest potential to attract and charge high prices to international students.

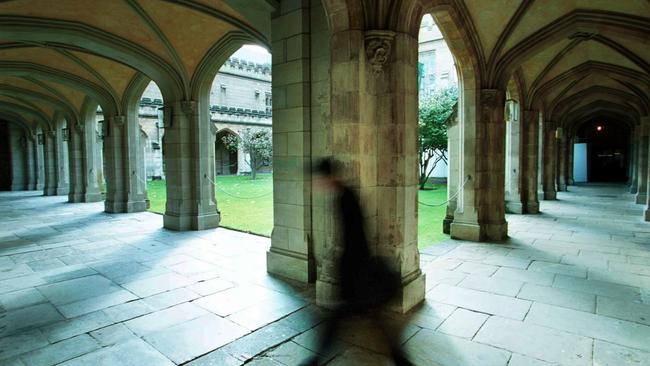

The other aspect of taxpayer subsidies to the most highly ranked universities, not immediately visible, is location. For example, the universities of Sydney, Melbourne, Queensland and Adelaide all benefit from not paying rent for some of the best-located properties in large, internationally famous cities. Through the major financial benefit of rent-free wonderful location, these universities are given a considerable advantage in the international student market.

So for reasons of both history and geography it has been, and remains, the case that Australian taxpayers are the important contributors to our top-ranking universities’ success internationally. Isn’t it then apposite that taxpayers should share some of this revenue via a small levy? Basic social welfare and economics tell us the case is incontestable.

The other major consideration is the price elasticity of demand for the international student market. What is this and why does it matter? The PED reflects the extent to which demand responds to price changes, and it matters for public policy.

In the international student fee revenue space the price elasticity of demand is a key issue because knowing the PED allows us to sort out what the implications would be for university revenues from a price increase resulting from a levy.

If the price elasticity of demand is very large, the international student fee revenue will significantly affect university revenue streams, but if it is very small this impact will be inconsequential at the same time a major revenue stream is generated for the government. So how big is it?

Our major contribution on the price elasticity of demand is to highlight that the international student fee revenue levy would apply to all Australian universities simultaneously, meaning the concept has to be understood at a national and not an individual university level.

We anticipate, with caution, that Australia, as a whole, has market power that mitigates against a high PED in this market.

One reason for this is time zones – Asian students studying in Australia have uncomplicated communication with family, which is not the case if they choose to study in Europe or North America.

There are additional national attractions: a vibrant and generally fair labour market; the weather; public safety; and our focus on equality and fairness.

The other, maybe the biggest, attraction of studying here is the prospect of permanent residency with accompanying major benefits (including high incomes and top-notch healthcare) because domestic university qualifications will significantly promote immigration prospects; it is notable that up to 15-20 per cent of former international students come here for life through the immigration program, and presumably others are enrolling in this hope.

In the end the size of the price elasticity of demand is an empirical issue, so we have consulted the experts.

The most knowledgeable of all researchers in this area is without doubt Simon Marginson (University of Oxford), who has written as follows: “There is no systematic study of PED but based on 25 years of observations, interactions and trend data I’m confident in saying that PEDs are very small in Anglophile universities and countries, except perhaps in lower-demand institutions” (private correspondence).

Thus in the view of the world’s foremost expert and others we consulted, the likely overall effects on international student fee revenue from a moderate levy and higher prices will be very small; however, there will be significant benefits as a return to taxpayers’ investments.

To illustrate this point, a 5 or 10 per cent levy on $10bn delivers around $500m to $1bn a year, which could be used to help all public universities support non-teaching activities if the government so decided.

This is a very big deal in terms of equity for taxpayers but should not divert attention from broad higher education funding issues, including for access and research. In a well-designed funding system there is a real possibility of making all our institutions better off via a levy on international student revenue.

Bruce Chapman is an emeritus professor of economics at the College of Business and Economics at the Australian National University and helped design the HECS policy. Rabee Tourky is Trevor Swan distinguished professor of economics and director of research at the ANU College of Business and Economics.

The debate is hotting up on the topic of a government levy on Australian universities’ international student fee revenue. This is critical for current policy, given the sums of money involved and the high proportion of the sector’s running costs from this source.