Your Right To Know is a cornerstone of democracy

The multiple veils of secrecy imposed by the federal government, and the states, have drawn media organisations together, including rivals with sharply contrasting priorities and editorial opinions. Democracy is about public accountability, as Michael Miller, executive chairman of News Corp Australasia, publisher of The Australian, writes, the principles at stake in the campaign transcend politics and media companies’ interests, which is why the disparate coalition comprises every major media outlet across the country. It includes News Corp, Nine, the ABC, commercial broadcasting networks, Sky News, The Guardian, Bauer Media Group, AAP and the journalists’ union. Between them, the players have the potential to reach every Australian adult.

Nobody, least of all The Australian, is disputing the importance of national security. But governments’ oft-cited concerns about security and privacy, as investigative reporter Hedley Thomas writes on Monday, are often “a ridiculous hoax’’. After decades of breaking penetrating exposes on everything from a dangerous surgeon known as “Dr Death’’ to incompetent dam management causing calamitous flooding, Thomas’s experience has taught him that the motive of government secrecy is often to minimise the risk of political embarrassment.

While police raids on News Corp reporter Annika Smethurst’s Canberra home on June 4 and on the ABC’s Sydney newsroom a day later might have served as catalysts for the campaign, its scope runs far deeper. The raids were the straws that broke the camel’s back, Miller acknowledges on Monday. Smethurst still faces possible criminal charges and jail: “Her alleged crime is that she revealed the government was considering secret plans to allow the Australian Signals Directorate intelligence agency to spy on all Australians. Why shouldn’t you know the government was discussing new powers that could let it spy on you and your family?’’ Indeed.

Constitutional lawyer George Williams believes Australia’s security and counter-terrorism laws lead the world in how they keep the public in the dark. “They are the sorts of laws one might expect in a police state rather than a democracy like Australia.’’ In order to redress the balance, the Your Right to Know campaign is demanding the Morrison government enact sensible, practical reforms to dismantle key measures being used to limit press freedom. Media organisations, the coalition argues, must be allowed to contest warrants by police. Exemptions must be provided for journalists from national security laws that make journalism an offence. The campaign is also calling for greater protections for whistleblowers and less documentation stamped “secret” that represses reporting. Media companies are also advocating a properly functioning FOI system and have revived long-held demands for defamation law reform at state level.

Misusing the veil of national security to avoid the truth is neither new nor uncommon, but it is increasing. Sky News CEO and former editor-in-chief of The Australian Paul Whittaker writes on Monday that Richard Nixon’s first comment on the Watergate scandal was that the break-in “involved matters of national security’’. Whittaker also recounts how a leak from a confidential source to The Australian 12 years ago, when he was the paper’s editor, saved an Indian doctor, Mohamed Haneef, who had been falsely accused of aiding terrorism, from spending longer behind bars. The transcript of the secret Australian Federal Police interview, leaked to Hedley Thomas, showed the Howard government’s line on Dr Haneef was as heavy-handed as it was misleading. Thomas’s report, published despite Whittaker facing a potential five-year jail sentence for doing so, delivered justice and scrutiny where the apparatus of government had failed: “The public interest was overwhelming and a man’s freedom was at stake.’’

In the case of Dr Haneef, his lawyer Stephen Keim SC, later outed himself as the source who risked his career as a barrister to bring the truth to light. Mr Keim’s public-spirited courage, like that of nursing sister Toni Hoffman, who blew the whistle on errant Bundaberg surgeon Dr Jayant Patel, as Thomas writes on Monday, underlined the importance of responsible whistleblowers. They serve the public interest by enhancing scrutiny. For good reason, Law Council president Arthur Moses SC is a strong advocate for greater protections for our independent press because “transparent government leads to better decision-making and a stronger democracy’’.

Serious restrictions on the public’s right to know extend beyond the commonwealth to the states. Of 855 suppression orders issued by Australian courts last year, more than half, 443, were handed down in Victoria. In many instances, even reporting the existence of such orders is a crime, as national security editor Paul Maley notes on Monday. Federal laws that allow police to raid the homes of journalists and fail to protect reporters who publish leaked material narrow the road for hard-hitting public interest journalism, Maley argues. That task is already difficult enough given the explosion of suppression orders, restrictive defamation laws and the absurd culture of secrecy that has penetrated every aspect of Australia’s bureaucracies.

At a time when almost nine out of 10 Australians (87 per cent) value a free and transparent democracy, but only 37 per cent believe it is happening, root and branch reforms are essential. More than three-quarters of Australians believe journalists should be protected from prosecution when they are reporting in the public interest and 88 per cent want stronger protections for whistleblowers. That would include Richard Boyle, who spoke out about the ATO’s ability to take money out of people’s bank accounts without their knowledge. He faces six life sentences if found guilty of 66 charges and describes the events of the past year as “hellish’’. We would condemn such a possibility if it unfolded in Russia.

The issue is much bigger than the media, as Nine Entertainment CEO Hugh Marks says. It is about the right of Australians to be properly informed about decisions governments are making in their name. Our nation does not want the distinction, as ABC managing director David Anderson says, of becoming the world’s most secretive democracy after two decades in which the public’s right to know has been slowly eroded by laws that make it harder for people to speak up when they see wrongdoing and for journalists to report those stories.

Readers coming to grips with the campaign should not be fooled by politicians’ claims that it is about media self-interest. “Nothing could be further from the truth,’’ as Miller writes. “This campaign is about you — and your right to know. You should always be suspicious of governments increasingly wanting to restrict your right to know. Democracy is about public accountability. We must never accept modern-day Australia is enhanced by governments being more secretive and hiding from scrutiny.’’

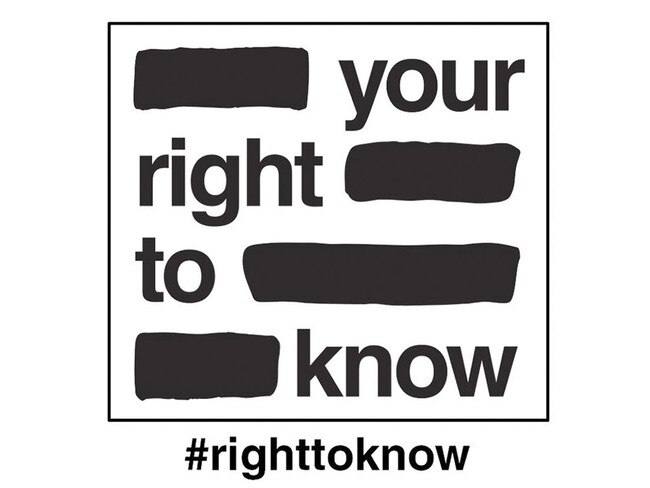

Odd as it may look, Monday’s front page has been heavily redacted to remind readers how much and how often the governments they elect and pay for are keeping them in the dark. The page, incidentally, resembles many of the responses doled out by governments, state and federal, to Freedom of Information requests. After about 75 pieces of legislation introduced by successive governments since 2001 creating roadblocks to stop you finding out what is going on across your country, enough is enough. A new campaign by Australia’s Right To Know coalition of media organisations is putting you, the taxpaying public first, emphasising your right to be informed about important issues. These range from thousands of reported cases of abuse in nursing homes and the misuse of taxpayer funds to the sale of Australian land to foreigners and the Australian Tax Office’s heavy-handed debt collection methods.