Whole-of-system approach needed on power reform

This is one of the key considerations that must be understood when judging Peter Dutton’s ambition to roll out a fleet of nuclear reactors to underpin the grid. Nuclear power, like coal and gas, can provide a steady and dependable supply, capable of underpinning the system and supplying the ancillary services, including frequency control, that otherwise must be paid for separately and at great expense.

This does not mean a nuclear plan will ever be easy, particularly given the lack of political unity on the issue.

But the onus must be on all sides of the debate to clearly spell out what their alternatives might be.

Despite the brave face being presented by Energy and Climate Change Minister Chris Bowen, the government’s renewables-only plan has been found wanting. Key aspects of it, including the construction of pumped hydro infrastructure and thousands of kilometres of transmission lines, are proving more difficult and expensive than expected to take from planning to reality.

Technologies that were supposed to replace fossil fuels both for export and domestic generation, such as hydrogen production, are proving technologically difficult to develop at scale at an affordable cost.

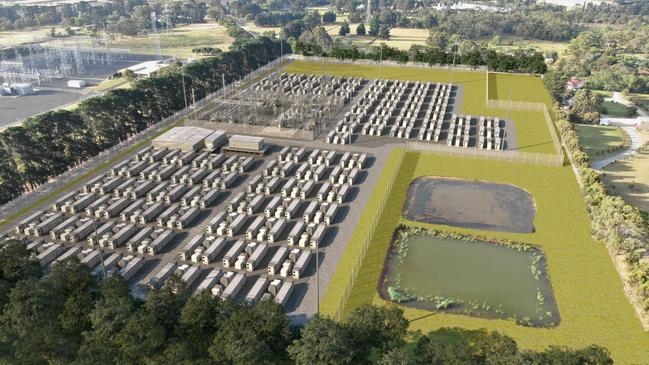

Battery technology is improving but does not provide a solution to the challenge of grid stability in times of extended renewable energy drought. These are all issues that were warned about by experts before Labor legislated its overly ambitious emissions reduction targets. They are all lessons being learned in real time in other parts of the world.

This is why nuclear has been put back on the agenda by the world’s biggest economies worried about the implications of disrupted supplies and the high cost of power, exacerbated by the vagaries of nature.

Australia has been cursed by a legislative prohibition on nuclear that was introduced at a time when coal and gas were not considered to be as controversial as they are today. A change in circumstance – prioritising zero carbon dioxide emissions – demands a change in approach, at least so that plans to introduce a portion of nuclear power can be properly considered. Modelling by Frontier Economics that shows the system-wide benefits of having a portion of nuclear energy are in the order of hundreds of billions of dollars deserves to be more thoroughly examined.

Instead, the Albanese government appears more concerned with the political theatrics of climate change action. This is amply demonstrated by the latest uncosted agreement signed at CHOGM between Mr Albanese and his British counterpart, Keir Starmer.

The Global Clean Power Alliance Finance Mission involves “further enhanced co-operation to ensure climate finance reaches those on the frontline of the climate crisis, particularly Pacific Island countries”.

The mission is to accelerate deployment of renewable energy technologies, such as green hydrogen and offshore wind. Both technologies are among the highest-cost, least mature options available, and struggling to find a role without large government subsidies.

The danger signs of what a renewables-only approach holds must not be ignored. A real-world focus is urgently required before we are left stranded by the overly ambitious promises being made by those who stand to profit most from offering solutions to problems of their own making.

The truth about decarbonisation of the energy system and economy is that the further you go, the more difficult and expensive it becomes. The so-called last mile will always pose the most difficult and expensive challenge. This is why maintaining a component of always-ready electricity supply to maintain the integrity of the network at times of low production from renewables can present oversized savings.