Plunge in standards drives distrust in our universities

Australian National University vice-chancellor and astronomer Brian Schmidt, who is the only university leader in the world to win a Nobel prize (for physics), made a telling point in his annual Foundation Day address this week. Australia needs universities more than ever amid the COVID-19 crisis, he said. But they have possibly never been more distrusted.

In an interview with Tim Dodd earlier this year, Professor Schmidt identified what families want universities to be. That is, a place where “Australian students can get an education as good as any place in the world but distinctively Australian”. That aspiration should serve as a model for our universities, which, since the days of the Colombo Plan in the 1950s, have attracted students from around the world for their quality and for the experience most students enjoy.

For decades the sector built on that reputation to the point where last year education had grown into the nation’s fourth-largest export, worth $40bn to the economy. For now, at least, the coronavirus has smashed the business model centred on international students. But that is only one of a range of problems facing the sector, as serious revelations reported in recent weeks have shown.

Most of these come down to the issue of standards, which university leaders must improve and defend if their institutions are to serve the nation and retain (or recover) their international reputations. Contentious cultural issues of academic freedom and censorship also loom large.

Suspicions that some institutions have “gone soft” in marking the work of foreign students have been rife for years. Alarm bells should be ringing among university leaders after confirmation that lecturers are being cowed into lowering academic standards by organised networks of overseas students. Academics admit they have “dumbed down” courses to ensure foreign students can complete degrees. Lecturers who refuse risk being targeted by official complaints signed by up to 100 students, as reported on Wednesday. It is even more alarming that such complaints are taken seriously by university executives and have the potential to derail academic careers. Language barriers are a major part of the problem, as local students know from experience. In defending standards, universities must insist on proficiency in English.

Recent scandals also show how far universities have strayed from what should be central to their raison d’etre — free speech and academic freedom. As Australian Catholic University vice-chancellor Greg Craven wrote recently, universities have two types of problems with freedom of academic expression. One is corporate, “where an academic writes something that could rile a major stakeholder: a sponsoring corporation, a government partner or — frankly — China”. Vice-chancellors understandably, but not heroically, Professor Craven noted, “feel for their institutional wallet”. The second assault on academic freedom is more insidious because it is internal. “An academic strikes trouble because he or she writes something counter to the accepted wisdom of their faculty or university as a whole.”

Despite an admirable policy on free speech, the University of NSW resorted to censorship when it withdrew a tweet quoting adjunct law lecturer and Australian director of Human Rights Watch Elaine Pearson criticising China’s miserable human rights record in Hong Kong. UNSW vice-chancellor Ian Jacobs, to his credit, has apologised for the decision to delete the tweet.

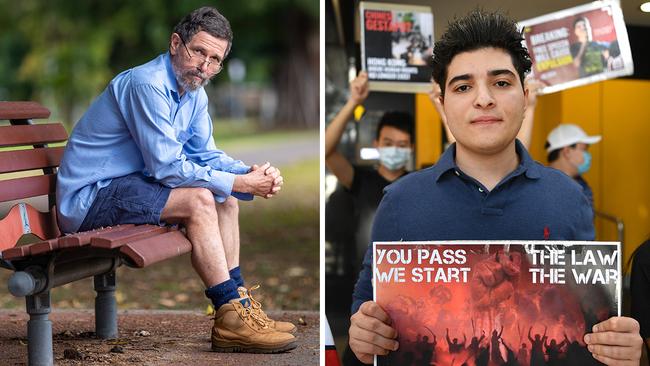

The suspension of pro-Hong Kong democracy student activist Drew Pavlou by the University of Queensland also smacked of repressive censorship. Both universities’ approaches were anathema to Western ideals of free speech. But Chinese Communist Party propagandist media, unsurprisingly, were deeply critical of both Ms Pearson and Mr Pavlou. Such erosion of intellectual integrity has compromised universities’ credibility.

The treatment of James Cook University physicist Peter Ridd by his employers also was indicative of an increasing hostility to debate on campus. The cardinal sin that brought about Dr Ridd’s demise was his questioning of the rigour of university-linked research on the health of the Great Barrier Reef under climate change.

Last year’s campus free speech report by former High Court chief justice Robert French made the point that university codes of conduct could be hostile to the freedoms they purported to uphold. That is particularly the case in relation to opinions that challenge progressive norms among academics. But when it suits them, some faculties prefer to turn a blind eye to empirical evidence. For instance, too many education faculties fail to prepare trainee teachers to use phonics in teaching children to read, despite impressive evidence about the method’s effectiveness compared with trendier “whole-word recognition” systems. Nor should promoting “cancel culture” be academics’ focus.

Regardless of such problems, universities remain our prime drivers of ideas and scientific breakthroughs. As Professor Schmidt said, few people realise how large and direct a part the ANU and other universities are playing in the fight against coronavirus. During the enforced interruption in their operations because of the pandemic, vice-chancellors and other leaders have a chance to raise academic standards, reinforce the value of free speech and improve accountability to taxpayers and to the Australian students who primarily fund universities. Doing so would rebuild trust and enhance their international standing.