Andrews, skilled politician with a lamentable legacy

Despite big swings against Labor in its traditional heartland in outer western Melbourne in the Victorian election last November, the Andrews government was returned to office for the third consecutive time, with an increased majority. It was bolstered by an ineffective opposition. But it won despite the fact, on the last day before writs were issued for the poll, Victoria’s mid-year budget update showed the state was on track by June 2026 to owe more in net debt than NSW, Queensland and Tasmania combined. About 4000 Victorian businesses and 860,000 landlords and holiday-home owners did not have long to wait to find out what the Andrews regime’s financial mismanagement would cost them. In May this year, Treasurer Tim Pallas’s budget imposed a “temporary” 10-year grab of extra land and payroll taxes. The imposts would make Victoria Australia’s “least attractive state to run a business or buy an investment property”, the peak body representing accountants warned. Despite extra taxes, the state’s debt is projected to continue rising. The state’s finances also have suffered through the expansion of the heavily unionised public sector workforce, which stood Mr Andrews in good stead at elections. Driven by leftist ideology, he took radical social policies to new lengths, often copied by other Labor governments.

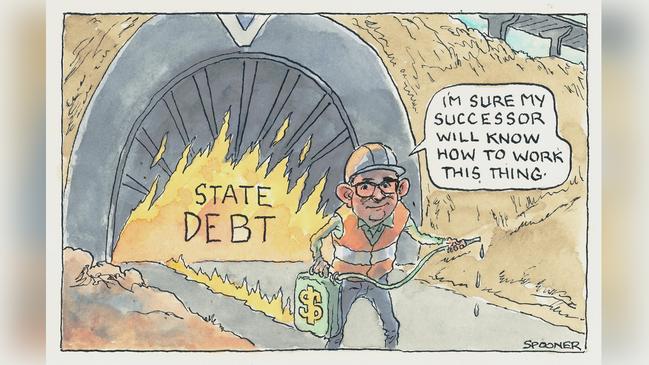

Whoever is elected premier in his place will face a herculean fiscal challenge that is too serious to be brushed aside. Unlike former Liberal premier Jeff Kennett, whose government was voted out after two terms in 1999, Mr Andrews does not leave Victoria in better financial shape than he found it. Mr Andrews’ financial recklessness became obvious early in his first term when he effectively set fire to $1bn in taxpayers’ money, abandoning the East West Link that would have streamlined two major road systems and help relieve commuter gridlocks. Victorians were forced, for no benefit, to pay $339m to the group previous governments had contracted to build the road, and a further $81m in fees and other costs.

The state also faces an uncertain energy future. While Mr Andrews pursued a relentless emissions reduction policy, he did not take enough account of the risks. Power prices have risen sharply, there is growing resistance to further renewable energy projects, including offshore wind, as well as new transmission lines, and the reticulation of gas to new homes has been banned.

On Tuesday, Mr Andrews caught his colleagues, the public, Labor factions and the media by surprise when he announced his resignation from the premiership and from his safe seat of Mulgrave in Melbourne’s southeast. Many expected that Mr Andrews would not serve his current full four-year term, despite his earlier assurances to the contrary. But his rapid and sudden departure, just 10 months into a four-year term, when he has no apparent plans, and announced in a week when attention is deflected by Saturday’s AFL grand final, will raise questions. He made the decision, he said, during the past few days. But his reference to “an old saying in politics, go when they’re asking you to stay” was no explanation at all. Is he getting out before the financial challenges get harder, some will wonder.

Had Anthony Albanese opted for a thorough inquiry into lessons that needed to be learned from the Covid-19 pandemic, including the states’ handling of lockdowns and school closures, it would be worth speculating that Mr Andrews was keen to avoid the fallout from such an inquiry. But the Prime Minister, unfortunately, has given the states a free pass. That is despite the fact the Andrews government’s quarantine hotel bungles contributed to 800 deaths and Melburnians were forced to endure some of the most draconian restrictions in the world, including a record of 262 days over six lockdowns across 2020 and 2021. The first began in March 2020 and lasted 43 days. In winter that year the longest continuous Covid-19 lockdown in the world occurred between July 9 and October 27, 111 days in all. The last ended on October 21, 2021, after 77 days of lockdown. Even then, limits on travel outside the city, the size of events and the opening of retail outlets continued. The adverse impacts on businesses, especially in Melbourne’s central business district, and on students’ learning and mental health, especially that of young people, are still being felt. At one stage, the draconian approach was reinforced with an 8pm-to-5am curfew in Melbourne. The approach reflected Mr Andrews’ deeply authoritarian instincts, also evident in his refusal to be interviewed by several fair-minded journalists he regarded as hostile, or more likely able to ask penetrating questions.

For all his loquaciousness, Mr Andrews had a penchant for secrecy when it suited him, especially in relation to his dealings with China on his most recent visit, which he did not let journalists cover, and in regard to his signing Victoria up to the Chinese Communist Party’s Belt and Road Initiative. That move surprised the federal Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and wisely was scrapped by the Morrison government.

During the height of Covid, Mr Andrews’ 100-odd daily press conferences, designed to show he was in charge, demonstrated his formidable skills at political theatre. For all his mistakes and controversies, Mr Andrews has had two major political assets on his side. One has been the opposition. The other has been his ability to brush aside crises, however damaging, by adopting a “nothing to see here” approach and moving on. Any successor, be it Deputy Premier Jacinta Allan, from the Socialist Left faction, or Public Transport Minister Ben Carroll, from the Right, would need time, even if they had the talent and ruthless determination of Mr Andrews, to develop and hone similar skills. To his own advantage, and that of his faction, his party, his government and favoured trade unions, those skills have seen Mr Andrews through scandals and crises that would have shaken most leaders badly. That gift of the gab saw him get away with too much, to the detriment of good government.

Mr Andrews was clearly emboldened by his ability to pull off a strong win in the 2018 election, despite the “Red Shirts” scandal centred on the misuse of taxpayers’ money for political purposes by the Labor Party during the 2014 election campaign. Another major scandal on the Premier’s watch included the government’s awarding a $1.2m contract to the Labor-affiliated Health Workers Union. In April, Mr Andrews claimed the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission report into the matter was “educational”, but he insisted there were “ no findings against anyone”. To the contrary, IBAC found “evidence of misconduct and improper influence” at the highest levels of his government. The lack of oversight of advisers by ministers – offering “the potential for plausible deniability” – raised questions about the “efficacy of the Westminster convention of individual ministerial responsibility as an accountability mechanism to parliament”, the watchdog found.

More recently, Mr Andrews’ backing of Socialist Left colleague and Climate Action, Energy and Resources Minister Lily D’Ambrosio again showed his Teflon defences. After revelations about a state branch associated with Ms D’Ambrosio, he could not explain why she should be treated differently to four other ministers who lost their jobs in 2020-21 over branch-stacking allegations, including rival powerbroker Adem Somyurek. Mr Andrews referred that matter to IBAC. But, despite Mr Somyurek and others on the Right claiming widespread branch-stacking had occurred in Mr Andrews’ own Left faction, IBAC confined its investigation to the Right.

After a probe by former premier Steve Bracks and former federal deputy Labor leader Jenny Macklin into branch-stacking, commissioned by Mr Andrews, only 13 of 132 members of the Lalor South branch continued to be registered with the party. At least two people had their signatures forged to have their memberships renewed after their deaths. Party documents also show that until July 2019, Ms D’Ambrosio’s branch was meeting in her electorate office once a month, long after an Ombudsman’s report into the Red Shirts rort highlighted Labor’s improper use of taxpayer-funded resources for political purposes. An IBAC report into the Andrews government’s relationship with the firefighters union is pending.

Regardless of who is elected by caucus to replace Mr Andrews, his departure should help level the political playing field. It will only boost the opposition if John Pesutto can unite his heavily divided team into a cohesive, competitive force, with policies to tackle the issues confronting Victoria. In the post-Andrews era, the nation’s second-largest state would gain much by a genuine, hard-fought contest of policies and ideas.

After nine tumultuous years as Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, 51, leaves office on Wednesday with two distinctions. One, he has been one of Australia’s most successful retail politicians of his generation. Two, he has been one of our second-largest state’s worst leaders, leaving behind a government drowning in scandal and an economy so weak it could not afford to stage the 2026 Commonwealth Games, a decision that has cost Victorians $380m in compensation to the Commonwealth Games organisation and far more in lost opportunities.