Now, however, Mark Scott, the vice-chancellor of Sydney University, has decided that Professor Sujatha Fernandes, who told her students that reports of Hamas committing mass rapes on October 7 were “fake news”, will escape with the slightest rap of the world’s lightest feather-duster.

How making statements that are demonstrably false can be anything other than a serious breach of the university’s requirement that academics respect the “highest ethical, professional and legal standards” is a mystery.

It is, after all, the very purpose of a university to encourage the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge: that is, of claims that can reasonably be held to be true. And it is no accident that the modern university’s emergence coincided with the rise of the notion that a commitment to the value of the truth, and of truthfulness in research and teaching, was academics’ foremost obligation.

At the heart of that commitment was the virtue of objectivity. The idea of dispassionately ascertaining facts was, for sure, hardly new. Thucydides placed it at the pinnacle of the historian’s merits, while Francis Bacon lucidly diagnosed the obstacles that stood in its way.

But the 19th century brought crispness and clarity to the concept. Until then, there was no single, unified term denoting a distanced and disciplined assessment of reality; if anything, “objective” generally referred to what we would today call “subjective”. Taking it to mean “viewing things as they really are” was revolutionary.

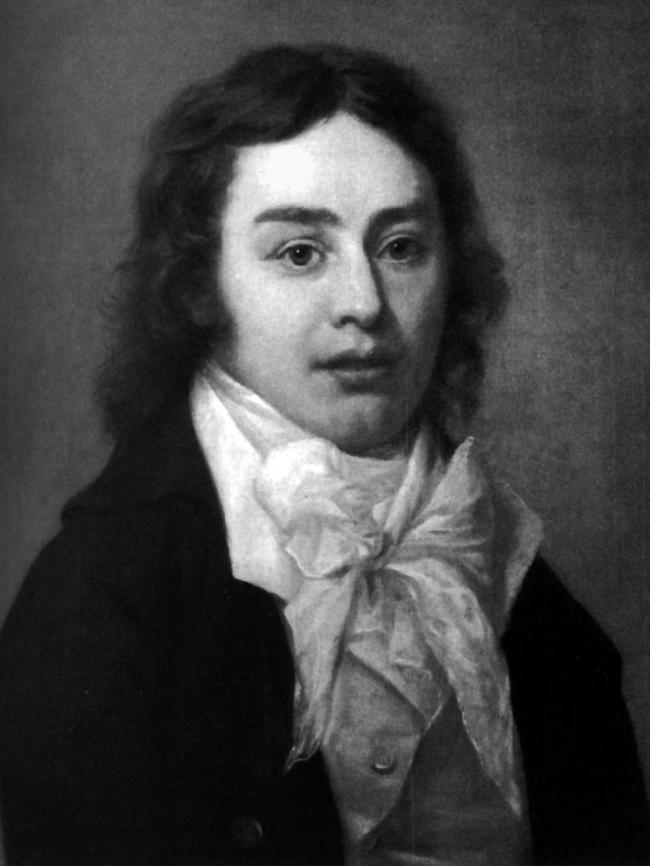

Indeed, so drastic was the change that when “objectivity”, used in its contemporary sense, first appeared in 1806, Samuel Taylor Coleridge assumed it was a mistake. By 1856, however, English man of letters Thomas de Quincy could marvel at how “objectivity, this word, so nearly unintelligible in 1821, yet so indispensable to accurate thinking”, had “become too common to need any apology”.

The term’s resonance was partly a reaction against European romanticism, which elevated emotion over reason. But the ideal of objectivity was also crucial in freeing scholarly endeavour from the stifling constraints of theology on the one hand and politics on the other. It did so by defining a new professional ethic, acquired through arduous academic training and implemented by suppressing prejudices, respecting strict evidentiary standards and honestly reporting successes or failures, uncertainties and conjectures.

Nor was this “scientific self”, which was invariably contrasted with the emotionally charged “artistic self”, limited to the laboratory or scholar’s study. By the first decades of the 20th century, there was broad agreement that it had to be fully on display in the lecture theatre, giving students a living example of how to think and learn.

That, Max Weber famously argued, was the entirety of academic freedom: the freedom to dispassionately seek, and equally dispassionately teach, the truth, with all partisanship abandoned – and even the slightest step beyond that transformed teaching into preaching, losing every protection academic freedom afforded.

No one could claim that Weber’s lofty ideals were always realised. But the ethic of objectivity proved crucial in the spectacular advances that marked every field of knowledge. Directly, it greatly enhanced the calibre of academic activity; indirectly, it provided users of research with quality assurance, facilitating the acceptance of controversial results.

Yet it has collapsed, most notably in the humanities and parts of the social sciences, to the point where Australia’s oldest, and once most prestigious, university considers purveying gross falsehoods a trivial offence.

It would be easy, but largely incorrect, to blame that collapse on writers such as Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault or Pierre Bourdieu. Rather, as Daniel Gordon and Nathalie Heinich have argued, the crucial factor was the rise, initially in North American universities, of centres – such as those dedicated to black, indigenous and women’s studies – that regarded advocacy as integral to their mission.

It was the growing tension that created with the ethic of objectivity, which abjured advocacy, that made the traditional academic virtues increasingly contentious. The arrival on the scene of Derrida, Foucault and Bourdieu therefore filled a need – a need, felt by activist academics in the English-speaking world, for intellectual legitimacy.

That those writers were comprehensively panned in France itself, where philosophy is taken seriously, scarcely mattered. To cite but one example, Jacques Bouveresse, undoubtedly the leading French epistemologist of his generation, dismissed Derrida’s work as nonsense.

Much as he may deride the concept of “the truth”, wrote Bouveresse, even Derrida, as he jets from conference to conference, needs to know whether it is indeed true that his flight leaves next Wednesday at three, rather than Thursday at five. And Bouveresse also showed that Foucault, who claimed to stand on Nietzsche’s shoulders, had grievously “mistranslated, misrepresented and misunderstood” everything Nietzsche had to say.

But what mattered to the activists was that Derrida, Foucault and Bourdieu argued that scholarship was inherently political. “Objectivity”, they contended, was a mere fig leaf for the interests of the ruling class.

Properly considered, the truth of a claim depended neither on how it was derived nor on its relationship to reality. It depended, wrote vastly influential American postmodernist Hayden White, on whether it was made from the right moral – that is, political – “standpoint”.

The way was therefore open to the development of what is now known as “standpoint epistemology”, which, in its most popular version, asserts that a proposition’s truth depends on the identity of its proponent. That is, of course, scarcely an inch away from Stalinism’s “proletarian science”, not to mention the Nazis’ “Aryan mathematics”. And if that epistemology was good enough for Stalin and Hitler, why wouldn’t it be good enough for Hamas and its taxpayer-funded acolytes?

That Fernandes channels Blanche Dubois in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire is therefore unsurprising: “I don’t tell truth. I tell what ought to be truth. And if that is sinful, then let me be damned for it!”

But what is surprising is that Fernandes gets away with it. For at a time in which values clash ever more loudly, and the public ever more strongly questions legitimate authority, protecting the objectivity ethic ought to be our universities’ highest priority.

In effect, just as the less politicians, bureaucrats or judges are trusted in a particular society, the more detailed must be its rules, so it has to be for scholars too. In a situation where consensus is elusive, the stringent quality assurance the rules of objectivity provide may well be the only thing that permits some shared understanding of reality to emerge – and with it, a shared appreciation of the constraints reality imposes.

No one would expect the activists, who thrive on chaos, to endorse that proposition. But Mark Scott ought to. And if he doesn’t, he should go.

If an engineering academic recklessly or deliberately misled students about how to build a bridge, Australians would not just expect that academic to be sacked; they would want to know, and would want every academic to know, that intellectual standards were being rigorously enforced.