With Labor now holding an unwieldy and already fractious majority, the Liberals under almost certainly transitional management, Reform UK up and the Canadian Conservatives down, Donald Trump’s role in all this needs explanation.

An alignment of electoral stars meant that much of the Anglosphere fought elections as Trump’s first 100 days unfolded. The spectre of Trump haunted America’s closest allies this campaign season, but it did so in different ways.

The UK moved towards the populist right – and the party led by a friend of Trump, Nigel Farage. Australia and Canada both had conservative parties that, in January, looked like they could win back power from failing governments of the left. Neither did.

As I argued in these pages, Trump is ambivalent about building a global conservative movement. His goading of Canadians as the 51st state bizarrely remade the incumbent Liberal government’s fortunes and weakened Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives, Trump’s natural allies.

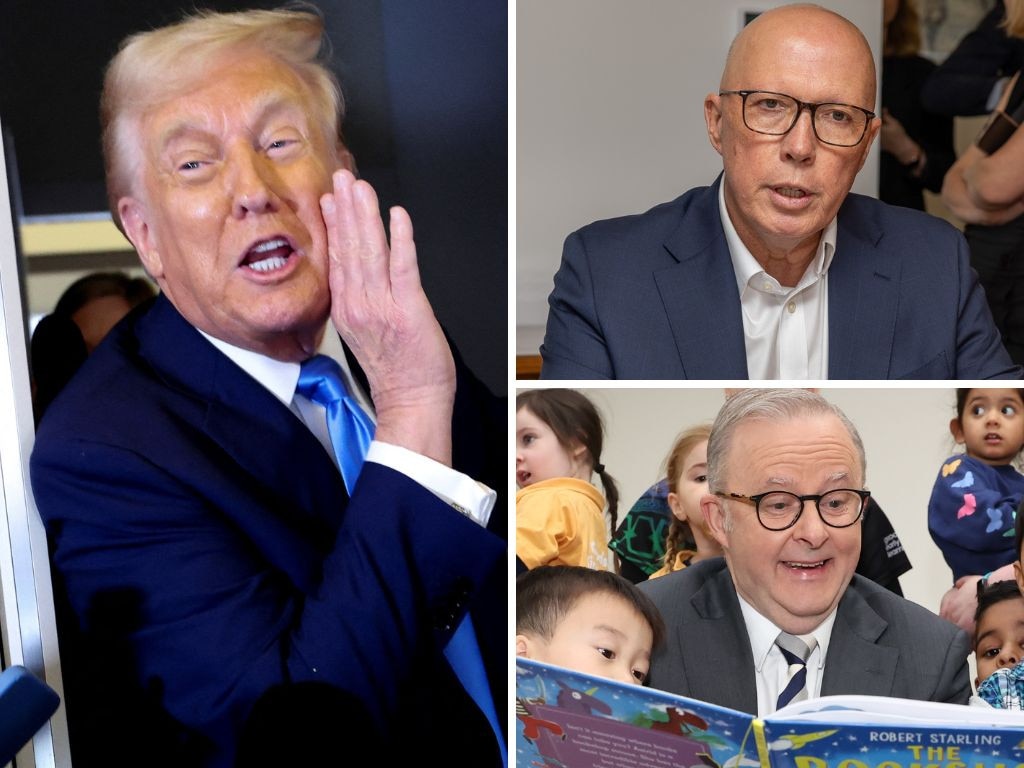

In Australia, Trump didn’t dent Coalition hopes as directly. But Labor acted as if he had. It worked. Anthony Albanese’s campaign succeeded in painting Peter Dutton in an orange shade. The LNP could not wipe off the fake tan quick enough.

Team Dutton said very few Trumpian things. When Jacinta Nampijinpa Price did, Coalition campaign HQ quickly closed her down. But Labor was clever at insinuating – as Trump’s tariffs hit our superannuation funds – that Dutton’s recklessness put him on a spectrum with the President. Rather than a Trump Bounce, Dutton’s political career ended in a Trump Dump.

Reform UK decisively bucked this trend. The Tories did not lose votes to Labour because of Trump. Rather, they shed council seats to the Trumpy Reform party. Kemi Badenoch, the Conservative leader, lost 674 of her councillors. Farage picked up 677 – no English party won more this month.

The New York Times saw enough in this to conclude that “voters have Mr Trump somewhere on their mind as they make decisions”. But on their minds how? How do we account for a variable Trump effect among American allies?

Answering that question needs a historical lens. The relationship of each of these nations to the US is different. England (1642-51) and America (1861-65) both have civil wars in their history. Like a divorce in a family, the legacy of civil war hangs around. Conflict is not quite endemic to British and American politics. There is, though, a willingness, of long genesis, to embrace ideological combat.

Australians have an electoral system that conspires to keep the middle in power. We have been told wars, especially about culture, are bad. We inflate the violence of Australian settlement to compensate for its essential mildness. We invent internal conflict to deepen national purpose. Externally, when America fights, we join them.

The US, in contrast, was born in a war against Great Britain. This foundational struggle gave it a taste for recurrently martial public policy. It has fought wars on banks (1830s), slavery (1860s), trusts (1900s), poverty (1960s), crime (1970s) and drugs (1980s).

To not have declared a “war on terror” after 9/11 would have been the exception to a historical rule. America has been declaring war on abstract nouns since its founding. Trump’s “war on woke” could plausibly be added to the list.

Presenting its opponents in such Manichean terms has long discomforted Canada’s progressive elite. It confounds their cultural relativism. Canada’s national identity has come to depend on a certain anti-Americanism. The Canadian Conservatives were unable to offer a pressure valve for this. The Canadian Liberals were. Mark Carney deftly parlayed a deep dislike of Justin Trudeau into an even deeper loathing of Donald Trump.

As The Spectator’s Andrew Russell argues, Aussies and Canucks feel the need to “performatively #resist” Trump. Brits don’t. Their national identity predates America’s existence. Canadians just hate being mistaken for Americans. Brits never are.

Australians? We are so dependent on America for our security, and on China for our prosperity, we must find ways to express our independence politically. On May 3 we became a pole to Trump’s America. Albanese’s strategic anti-Americanism damaged Dutton much more than anything the hapless Coalition leader actually said.

Labor tapped an Australian disdain for the US, made worse by Trump’s war with Adam Smith – “Smith won”, quipped a relieved Wall Street Journal editorial this week – and his wider culture war, which the disarray of the Democratic Party suggest he is winning. Team Dutton was at best pusillanimous in resisting the populist caricature the ALP made of it.

Nigel Farage, in contradistinction, prospered by his embrace of Trumpian populism. There was no anti-America sentiment, as in Australia and Canada, to help his opponents make Reform populism suspect. Labour and the Tories avoided doing it.

Indeed, these legacy parties are starting to warm to a more sceptical position on mass immigration. We might call this a MAGA-Reform effect that may eventually hit Australia shores. But not yet.

Reform UK told voters: “You are worse off, both financially and culturally.” The LNP Coalition was only ever willing to make the first claim, despite believing the second.

Consider this Reform pitch: “Wages are stagnant, we have a housing crisis, our young people struggle to get on the property ladder, we have rising crime, energy bills are some of the highest in Europe, the NHS isn’t working, both legal and illegal immigration are at record levels and woke ideology has captured our public institutions and schools.”

Dutton was too timid and/or poorly advised to adapt it for Australian consumption. When it came to Trump, Peter did not know the Galilean. “I don’t know Donald Trump; I’ve never met him,” said Dutton. He treated Andrew Hastie much the same.

It appears Dutton’s partyroom took its inspiration from Trump 1.0. That first term was chaotic. The Coalition did not expect to win and lacked a plan. This was Dutton’s campaign in a nutshell – without the winning part.

Trump 2.0 is different. Winning was expected and planned for – a 922-page plan called Project 2025. The Coalition frontbench had nothing equivalent.

The ALP was much cannier in dealing with the Trump effect. Albanese evidently watched how Trump prospered as an anti-woke warrior. He determined he would not offer Dutton that target. He campaigned from the Labor centre. He eschewed cultural issues. He dropped the voice like a stone; this left Dutton few to throw back at him.

We live in the Age of Trump. It would be hard to imagine any election in an English-speaking ally of the US being immune to its effects. The Middle East, this week, surely entered that Age.

But the Trump effect, as befitting a leader who prizes chaos as a tool of presidential power, is not uniform. Its depth depends less on the man himself and more on the historical forces that bind nations, such as ours, to his. The Australian Labor leader understood this better than his Liberal opponent.

Timothy J. Lynch is professor of American politics at the University of Melbourne.