I normally wouldn’t buy indoor plants because we move around a fair bit. But my green-fingered neighbour has kept this plant alive all that time. It prompts me to ask the question: did Covid really change anything, at least economically speaking?

In some respects, the post-Covid world looks better than before. After all, the rate of unemployment has been below 4 per cent from early 2022 compared with a rate close to 5 per cent going into the pandemic. The employment-to-population ratio has jumped by more than two percentage points and the participation rate is at a historic high.

When the pandemic first broke out and state governments, in particular, began to impose restrictions, including periods of lockdown, there was a widespread view that property prices would plummet, with any recovery very uncertain. As events panned out, property prices fell briefly but have since recovered, and a bit more.

With the exception of those quarters that significantly were hit by lockdowns – the June quarter of 2020 and the September quarter of 2021 – gross domestic product has continued to grow.

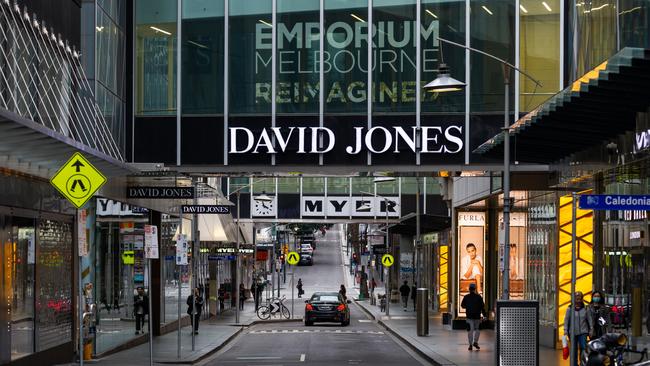

Certainly, many small businesses were hit for six by government actions, but the overall economy continued to grow. With the opening of the international borders, the absolute level of GDP has been inflated by the surge in net overseas migration, in part reflecting a catch-up for the period of closed borders.

It is important to note here that Australia has recorded falling per capita GDP this year.

The reality is that the real economic impact of Covid is not easily detected by simply observing the surface; it’s necessary to have a look at what’s going on underneath to make an accurate assessment. It may look like business as usual, but there have been several fundamental economic changes with ongoing consequences.

One of the most obvious fiscal features of Covid was the extremely large jump in government payments as households and businesses were supported in various ways to offset the impact of the imposed lockdowns and other restrictions. Federal annual real government spending went from $550bn before the pandemic to $654bn in 2020-21; from 24.6 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 to 31.4 per cent in 2020-21. This is an extraordinary increase, with net government debt increasing by $100bn in one year alone (between 2019-20 and 2020-21).

Two important points flow from this step-up in government spending. The first is the circularity of the arrangements; the state governments would not have been able to impose the lockdowns, border closures and other restrictions were it not for the federal government compensating households and businesses. Had the benefits been more limited, these governments would have had to give much more thought to the policies they implemented. In addition, the relative ease for some workers to work from home enabled the lockdowns to be ordered to an extent that would have been unlikely in the past. (The WFH phenomenon continues, with uncertain but probably damaging effects on worker productivity.)

There is also an argument that people went along with the limitations, notwithstanding their inconvenience and madness in some cases, because people were being compensated. This may bode badly in the future, with people now expecting the government to pick up the tab in the event of any adverse development such as the pandemic.

The second point is the seemingly permanent increase in the size of government, post the pandemic. This is the case for both federal and state governments. For example, if we look at the latest federal government mid-year economic and fiscal outlook, government spending remains above 26 per cent of GDP in every year to 2026-27. In other words, government spending looks like a one-way street: ratchet it up and don’t expect a return to the previous size of government.

Of course, it wasn’t only governments involved in offering economic support for the damage caused by Covid – or, to be more precise, government measures to deal with Covid.

The Reserve Bank was quick off the mark, implementing rapid cuts to the cash rate as well as engaging in quantitative easing. For those with a mortgage (or debt of any sort), monthly repayments quickly began to fall and many households were able to lock in low fixed interest rate mortgages for several years. Unsurprisingly, the combination of cheap money and the massive surge in government spending set the scene for potential inflationary pressures to emerge. In the context of global supply-side problems affecting many goods as well as building materials, it was only a matter of time before inflation would become a problem.

(For a time there was some political discussion of the need for local production of key goods, including pharmaceutical and technology products. With the exception of the US pushing on with local computer chips manufacturing, there has been little progress with this so-called on-shoring.)

All those years of very low inflation had seemingly inoculated policymakers from the dangers of sparking inflation through faulty policy settings. Demonstrating that things were overdone during the pandemic, we only need to look at what happened to the household saving ratio. Going into the pandemic, the ratio stood at 7 per cent of gross household income. Seven months later, it was 24 per cent; it was 19.2 per cent in September 2021.

To be sure, people were not able to spend money on certain goods and services and this partly accounts for the rise. But it’s not surprising that many households felt less financially pressured during Covid than before.

If we look at the most recent figures, however, we observe that those savings have been almost completely depleted, with the saving ratio a mere 1.1 per cent in the September quarter of 2023.

It’s understandable that policies decided during periods of great uncertainty – the onset of Covid is an example – can be highly defective (and ineffective). Everyone was uncertain about the seriousness of the virus, how quickly it would spread and what public health measures were really required.

Of course, Australia was not Robinson Crusoe in making these mistakes and, on the face of it, inflation is now returning to within target ranges in many countries. But there was no excuse for overlooking the economic policy lessons of the past and ignoring the risks that were being run by massively increasing government spending as well as running effectively zero interest rates.

Real household disposable incomes are now being hammered, making for lots of grumpy consumers (and voters). My peace lily seems blissfully unaware.

I am sitting at my desk looking at the peace lily that, amazingly, has a few flowers. I can remember when I bought it – the day the Morrison government closed the international borders as a precautionary measure given the outbreak of Covid in China.