Delay migrant intakes until infrastructure can catch up

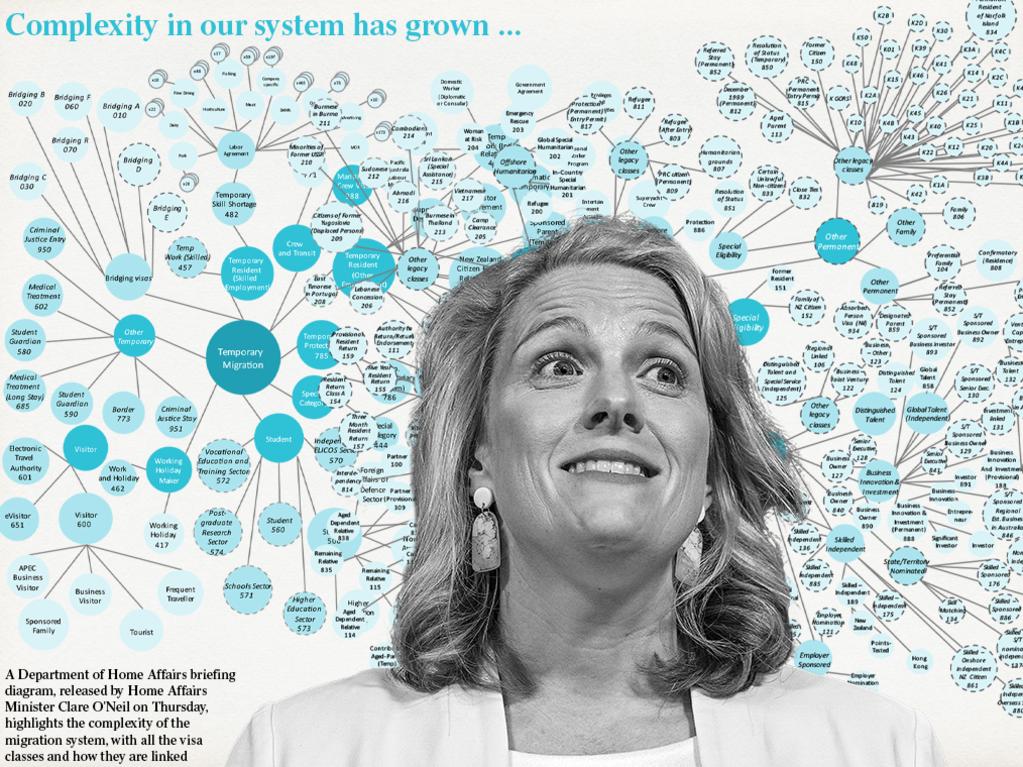

There is no doubt that our immigration system is an untidy hodge-podge of visas, both permanent and temporary, that has grown like Topsy over time. To say it is not fit for purpose is to understate the point. The compliance costs are high, the delays often unacceptable and many of the visa categories clearly fail to fulfil the objectives set down for them. The fact that there is an imposed annual cap on permanent migrants but none on temporary migrants makes no sense.

Historically, there was very little scope for temporary migrants to come here: people (and their families) came for keeps and the architecture of the visa arrangements reflected that feature. In the past two or so decades, however, temporary entrants have come to dominate annual migrant inflows.

The largest group of temporary entrants is now international students, although it is clear that very many of these students, particularly those from India, have every intention of staying permanently in Australia if they can. In some cases, it’s not even clear that education is their main motivation for coming here in the first place. There are currently some 1.8 million temporary migrants living in Australia.

Before assessing the recommendations of the review of the migration system commissioned by Home Affairs Minister, Clare O’Neil, and chaired by former bureaucrat, Martin Parkinson, it is worth laying down some uncontested findings about the impact of immigration. These are:

• Immigration has a very small effect on the ageing of the population because migrants themselves age;

• Immigration has a small positive economic effect, in per capita terms, over the medium term, but most of the gains are captured by the migrants themselves;

• It is only skilled migrants who make a net fiscal contribution; other entrants are a net drain on the budget;

• The timing of immigration matters; it’s unwise to allow large number of migrants to enter when housing market conditions are extremely tight, for example.

This latter point is very important because the current high rate of migrant intake (as reflected in net overseas migration) is placing additional pressure on rental accommodation and contributing to higher rents. Moreover, what is normally seen as a plus – that immigration adds to both demand and supply – is actually a negative at this point, as the Reserve Bank and the government attempt to cool demand (and the associated inflationary pressures).

While it is tempting for the government to open the flood-gates to more migrants to deal with today’s labour market shortages, some of these shortages may well prove to be short-lived. The use of migrant workers also undermines the incentives for employers to train local workers, instead relying on importing skilled labour.

Turning to the final report of the review which was released on Thursday, there are some sensible recommendations although the prominence of bureaucratic appendages is disappointing. The recommendation for a reformed Ministerial Advisory Council on Skilled Migration, for example, is really just an efficient means of rent-seekers in this space – think universities, property developers, some employers, migration agents - accessing the minister.

As for the recommended role of Jobs and Skills Australia, labour market planning and forecasting were discredited a long time ago. There is no reason to think this sort of agency can undertake useful analysis to inform the government. The fact that the review actually recommends the abolition of the occupational lists that drive some visa categories underscores this point. That said, the recommendation that labour market testing be done away with is sensible.

Unsuprisingly, the value of immigration is strongly emphasised in the review while the costs are downplayed. It calls for better planning, particularly in respect of infrastructure. But how long have we been hearing this plea; the reality is that it is probably best to delay migrant intakes until the required public facilities have caught up.

There is also a strange disconnect in the final report by pointing to the unacceptable treatment of some temporary migrants as well as their uncertain paths to permanent residence while essentially recommending that we clamp down on temporary migrant entry, particularly leading to PR. The report talks about identifying only the ‘best’ students as being allowed to stay and imposing higher salary requirements on temporary workers. (By the way, when did ‘guardrails’ become the latest buzzword?)

And having told us that we need to place stronger emphasis on skilled migrants, although there may be some scope for less skilled ‘care’ occupations being granted visas, the review recommends that a lottery be created to allow migrants to bring in their parents. This has the effect of diluting any beneficial impact on ageing as well as potentially imposing costs on society because these parents will be older.

For my money, I would have called for the abolition of all the ‘golden money’ visas, including the Business Innovation and Investment Program, the Significant Investor Visa and the Global Talent Visa. Not only are they subject to manipulation and rorting, it’s not clear what net contributions they have made to the Australian economy. Note here that the migrants under these visa categories also tend to be older.

The most fundamental weakness of the review however is its disregard for the views of Australian citizens, as demonstrated in multiple surveys, who have firmly expressed their opposition to high rates of migrant intakes. Without evidence, the review talks up the “Australian success story” in which more people living in Australia were born overseas than at any other time in the last 130 years – “the richly diverse, dynamic and multicultural Australia of today”. We deserve more than flowery rhetoric in a serious review.

I have been writing about immigration for a long time. It is a fraught topic: there are strongly held views, both pro-and anti-immigration. The point I have always wanted to emphasise is that immigration involves both benefits and costs and it is the balance between these two that matters. There is also the issue of who bears the benefits and the costs when determining optimal policy settings.