DeepSeek shows tech’s a monster, but we can tame it

More than 200 years have passed since the publication of Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, Frankenstein. Yet, when it comes to the human condition and the opportunities and challenges new technologies present to humanity, surprisingly little has shifted.

At the crux of this seeming immutability lies a basic truth – it is not the technology that is bad; rather, it is how people choose to use it.

In Frankenstein, Shelley observed that: “Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos; the materials must, in the first place, be afforded: it can give form to dark, shapeless substances, but cannot bring into being the substance itself.”

In 2025 – as has been the case since the dawn of time – humankind finds itself in another race for technological supremacy. Today, however, the technology is not hewn of wood or stone, but of chips and wires. Artificial intelligence is here to stay and will have an increasingly profound impact on the way we communicate, work and play, on politics, policy and geopolitics. The big challenge for Australia, therefore, as a net consumer of AI, is how to create the right settings and safeguards to ensure the use of AI technologies by our governments and organisations is responsible?

Over the past week the significant impacts of international AI policy have been on display.

In one of his first acts as President, Donald Trump announced the Stargate Project, which aims to build $US500bn ($801bn) worth of AI infrastructure in the US via a powerful coalition of OpenAI, Oracle, SoftBank and MGX. Much like the US push into enhanced semiconductor production via the CHIPS Act, Stargate is aimed at building real technology competition in a market China has aggressively pursued and upon which the world relies.

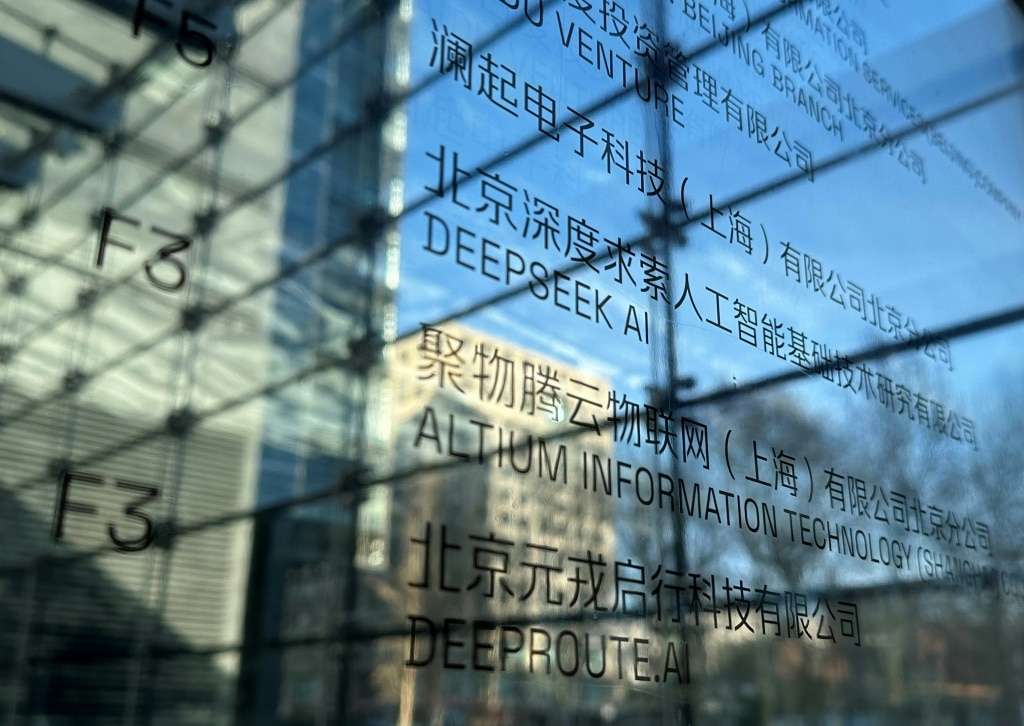

However, the fanfare of the US announcement has been overshadowed by a Wall Street grenade, with the launch of DeepSeek’s R1, a Chinese-developed generative AI (GAI) model that has been found to perform better than OpenAI’s comparable tech.

Also, DeepSeek’s technology is significantly cheaper to train and develop, which means it will be highly attractive to organisations wanting to implement GAI systems but struggling with budget.

The announcement of the technology’s apparent efficacy sent the US stockmarket into a panic, with Microsoft, Tesla, Nvidia and Broadcom all experiencing losses. Indeed, the shockwave prompted US tech billionaire Marc Andressen to proclaim that “DeepSeek R1 is AI’s Sputnik moment”.

So what does this global competition mean for Australia? As previously noted, we are and will ultimately continue to be consumers of AI, not large producers of these technologies.

Therefore, in an age defined by a global technology race, Australia is confined in relation to the impact it can have on a geopolitical stage. But there are things that can be achieved domestically via policy and regulatory settings that can help Australia take advantage of AI innovations while also mitigating potential risks. However, they must not be knee-jerk reactions.

The federal government’s significant consultation on mandatory and voluntary AI guardrails has helped set the scene for what AI regulation in Australia may look like. But while engagement from government has been strong, the proposed guardrails remain very broad and, in practice, may be difficult and expensive to implement.

In this regard there are also big lessons for Australia to take from the EU experience and the implementation of the AI Act, a cumbersome tome of legislation that frequently contradicts itself and other pieces of EU law. Indeed, a recent European Commission report into future EU competitiveness by former European Central Bank president Marion Draghi noted that “the EU’s regulatory stance towards tech companies hampers innovation”.

Then there is the elephant in the room: energy supply. AI systems and the data centres they rely upon use vast amounts of energy. For Australia, which is aiming for net zero emissions by 2050, this may be one of the toughest hurdles to overcome. Furthermore, as operational prices surge, it may also push Australian organisations towards vendors who can provide AI technologies more cheaply – vendors such as DeepSeek.

This is not inherently bad because tech competition is good. But as has been the case with other Chinese companies and potential security risks associated with 5G technologies, some level of caution must be applied.

Therefore, there is a key role for Australia’s national security establishment to play in helping ensure that Australians are protected from threats including foreign surveillance, social engineering and data hoarding.

When it comes to AI, there are many doomsayers but the stark reality is that AI is here to stay and, if not embraced for the opportunities it presents, Australia risks being left behind.

Sensible regulation that fosters, not hinders, innovation is vital. As is the understanding that, just as Shelley observed in 1818, it is humans that control the technology and the outcomes it brings, not the technology itself.

Anne-Louise Brown is head of strategy and Iisights at Akin Agency. She was formerly the director of policy, Cyber Security Co-operative Research Centre.