After all, the Commission’s members are not wild-eyed radicals; yet their report is as uncompromising in its hostility to this country’s past and present as it is remote from any semblance of objectivity.

At the heart of its 400-page tirade is the theory of “settler colonialism”, which was developed by Australian anthropologist Patrick Wolfe and his successor at Swinburne University, Lorenzo Veracini. Adopted wholesale by the Commission, that theory distinguishes “settler colonies”, where the “colonisers come to stay”, from those in which colonialism’s overriding purpose was to extract resources.

The salient feature of settler colonies – epitomised, it seems, by Israel and Australia – is their relentless “logic of elimination”: because Indigenous inhabitants “stand in the way of the colonisers’ settlement and occupation”, the settlers’ overriding objective is to “destroy First Peoples’ ownership and presence”.

Irreversibly marked by the “complete rejection of the equal dignity and humanity of First Peoples”, the settlers’ genocidal project of “elimination and erasure” has, the report claims, shaped this country’s “governance of Aboriginal people across three centuries”.

And nowhere have the impacts been more pronounced than in the justice system, which has “criminalised (Indigenous Australians) for resisting state intervention, maintaining their sovereign rights and not complying with imposed Western laws”.

Nor is that merely a description of the past. Rather, perpetuated by the “deliberate inaction” of Australian governments, and legitimated by criminal statutes that judge Indigenous Australians through “a Western moral lens”, the justice system’s “gross human rights violations remain alive in the present”, condemning Indigenous Australians to spiralling rates of incarceration.

Taken individually and in aggregate, those contentions are simply indefensible. Reducing reality to a binary conflict between hapless victims and diabolical perpetrators, they erase all the complexity of this country’s experience.

And instead of being merely a black armband view of history, their Manicheanism is a black blindfold, which shields the Commission from ever having to see, much less address, the contradictions between the factual record and its errors, half-truths and omissions.

It is consequently unsurprising that the report’s lengthy account of the Australian criminal justice system’s relationship to Indigenous Australians never cites Heather Douglas and Mark Finnane’s Indigenous Crime and Settler Law (2012), which is widely regarded as the standard text in the field.

The omission is readily explained: Douglas and Finnane, who are scarcely right-wing, painstakingly show that policing and law, for all of their appalling failures, “protected settlers and Indigenous people, the latter also from the unrestrained depredations of the former”.

They show too that our judicial system, far from being remorselessly genocidal, was constantly anguished about its interaction with Indigenous peoples, and – in a never-ending effort to acknowledge Indigenous “customs” – displayed a cultural sensitivity that clearly exceeded that in comparable jurisdictions overseas.

And last but not least, they demonstrate that the major area where the system struggled to reconcile its cultural sensitivity with its commitment to protecting human life was in dealing with the savagery that hit not only Indigenous women but also children, who were murdered for alleged acts of witchcraft.

The report’s distortions of the past pale, however, compared to the flaws permeating its analysis of the present.

One fact alone highlights its crippling intellectual thinness: the report simply ignores the analyses that show that high rates of Indigenous imprisonment are very largely, if not entirely, explained by high rates of violent, repeated, offending. Working carefully through its hundreds of pages, the reader would never learn that leading criminologists had demolished the contention that Indigenous imprisonment rates reflect systematic racial bias.

Nor does the report recognise, in its outraged discussion of detention on remand, that if the numbers confined have increased, that is primarily because legislators, so as to protect the most vulnerable of victims, have made it harder for those accused of grievously injuring women and children to be granted bail.

None of that is to deny the high rates of Indigenous incarceration are a national tragedy and a national disgrace. But it never crosses the Commission’s mind to ask whether, rather than chronic disadvantage, those rates might reflect the poisoned advantage our policies have bestowed on so many Indigenous Australians by encouraging them to live lives disconnected from productive activity and hence from the dignity, stability and security it provides.

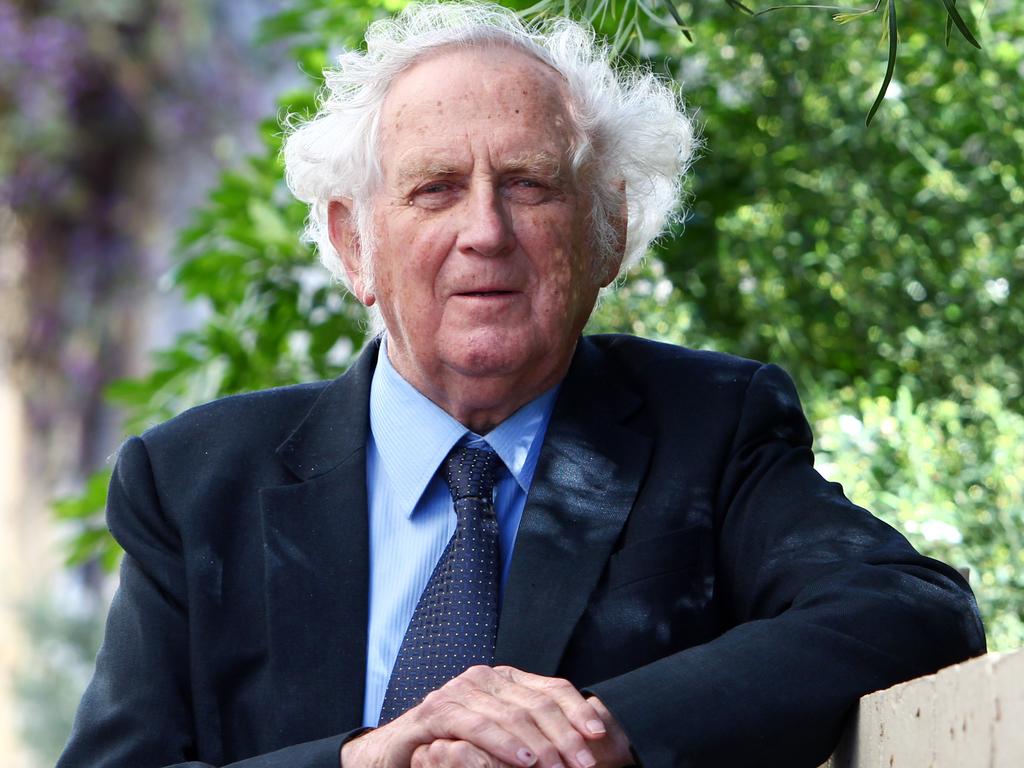

As for the inconvenient fact – carefully demonstrated by Don Weatherburn, Australia’s most eminent statistical criminologist, in Arresting Incarceration (2014) – that the steep rise in Indigenous incarceration rates began when the much-maligned objective of integration was abandoned for policies that (under the guise of “self-determination”) encouraged de facto segregation, the report buries it in convenient silence.

Instead, it demands that the failed policies be pursued to even greater lengths, replacing equal treatment under law by a system in which the colour of one’s justice would be determined by the colour of one’s skin.

The premise underlying its recommendations is that the “colonisers” must, as Veracini put it – in words that resonate throughout the Uluru Statement’s background documents – accept that their only choice is to “either physically remove (themselves) from the land” or “remain as guests, paying rent”.

That at least 20 of the report’s 46 recommendations would create lucrative opportunities for Indigenous elites not only effortlessly combines the arrogance of moral certainty with the baseness of enrichment; it also starkly foreshadows where the torrents of dollars would go.

Yet the question remains: How has it come to this? How is it that prominent members of the Indigenous elite have adopted attitudes and demands once confined to the fringe?

It is hard, in contemplating that question, not to be reminded of Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that if France’s intellectuals had, under the ancien regime, become “ever more fanatical in their beliefs, ever more out of touch with practical politics”, it was not because they encountered so much resistance but so little.

Positively celebrated for indulging in intellectual “follies”, they had every incentive to push their delusions to the wildest limits – and no incentive to worry about the consequences, which ultimately proved disastrous.

That, surely, is what has happened in our approach to Indigenous Australia. Wracked by guilt, longing for redemption, ever willing to be accommodating, we jettisoned the ballast that could have kept the debate moored to the reality principle.

Little wonder then that that approach now risks a grim reckoning in the referendum, where its disconnection from Australians’ expectations is becoming clearer by the day.

And little wonder too that Indigenous elites, colliding at last with the real world, are descending into paroxysms of fury.

As illusions shatter under the impact, the aftermath will come shrouded in dust and ashes.

The most striking feature of the Yoorrook Justice Commission’s report into Victoria’s child protection and criminal justice systems is its pure and unalloyed extremism.