These positions will make Coalition voters doubly wary. Howard, while not adopting a final position, is obviously concerned and guarded. Given his standing, any Howard refusal to endorse the referendum would be fateful.

But Turnbull, in his essay in Guardian Australia, has shattered much of the pro-voice mythology by saying the proposal is about “power”, that the concept is “politically very challenging” and that it will be hard to pass laws that are opposed by the voice.

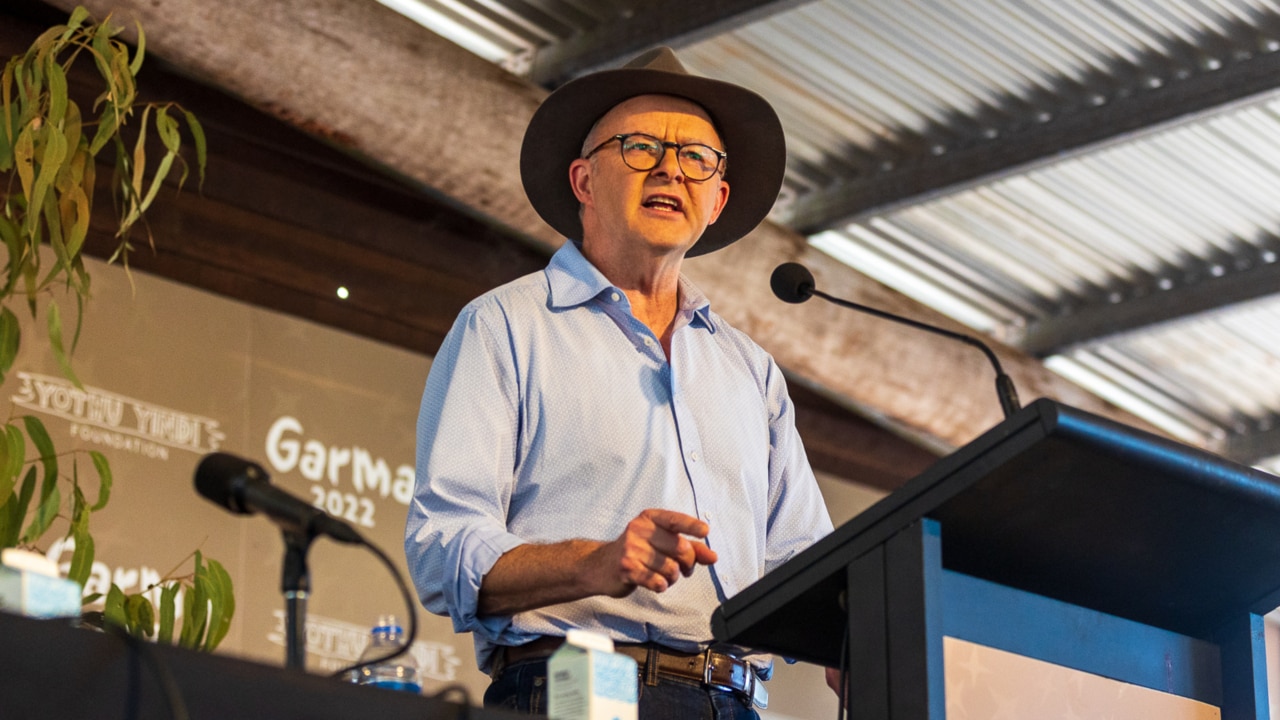

Political reality is about to penetrate this debate. The tactic of voice backers to present this as an open-and-shut case of historical justice won’t work. The proposal is complex and one of the most far-reaching changes since Federation. Turnbull says we must find “in our hearts to vote yes” yet he offers a series of doubts to reflect upon in our heads. This is why the Albanese government must outline the principles of the design before the people vote.

As for Howard, he warns in his new book, A Sense of Balance, that “I do not believe that the Australian people will vote for major changes to our Constitution, even if they enjoy bipartisan support.” By most analyses, witness Turnbull, this is a major change. And, so far, it lacks even bipartisan support.

Pivotal to the coming debate is the stance of the Coalition and conservatives, and this raises two decisive questions. Will the conservatives, instead of defining themselves by what they oppose, actually explain what sort of voice they would support? And do the Labor Party and Indigenous leaders have any real interest in making concessions to win bipartisan support?

The Liberal Party is damaged goods these days. It cannot keep running on negatives. The Coalition’s current majority disposition is opposition to the voice, a proposal about which it feels no ownership while also holding serious and genuine concerns.

But pure opposition to the voice is not a tenable position. It cannot be the final stance taken by the Peter Dutton-led Coalition. This debate was triggered before the 2007 election when Howard as PM, in dialogue with Noel Pearson, embraced the commitment to Indigenous recognition in the Constitution. Every Liberal PM since – Tony Abbott, Turnbull and Scott Morrison – has backed this principle. The Liberals lack ownership of the voice but have ownership of the constitutional recognition principle.

Being purely negative dishonours this history. The Coalition has agency, immense agency, in this referendum. It can be constructive or destructive. The Coalition can defeat this referendum. This is implicit in Howard’s analysis. Turnbull said if there were “concerted opposition” the referendum “will likely not succeed”.

Lawyer and supporter of Indigenous rights Father Frank Brennan, in his Newman Lecture last week, said: “One thing is certain. There will be no point in the Labor government proceeding with a referendum unless and until all major political parties in our parliament are agreed on the shape and scope of the voice. If in any doubt about that, just remind yourself that the Labor Party has made 25 attempts to amend the Constitution since Federation and they have failed on 24 of those occasions.”

Some pro-voice advocates think they have history with them and can carry the referendum on its vibe without offering any detail. This is the path to ruin. Any such bid would be branded a “fraud on the people” or a “politicians’ voice” and be sunk. If Anthony Albanese tried that tactic it would guarantee the Coalition’s resistance with Labor virtually writing the No case.

Assuming that Labor, as Brennen says, must engage in what sort of voice it envisages, then surely a reciprocal onus rests on the Coalition. Brennan put the crucial question for conservatives: can the voice be reconciled with the current constitutional order?

He believes it can. Brennan said the Coalition should support a voice “by which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are consulted prior to the enactment of laws that apply especially to them”. At present section 51 (xxvi) of the Constitution says the parliament can make laws “with respect to the people of any race”.

Brennan asks: how can conservatives deny a constitutional provision for Indigenous peoples to be consulted in relation to such laws? But this envisages a voice far different to that so far suggested by the Albanese government, though the PM says he doesn’t want to be “overly prescriptive”.

Under Brennan’s proposal the voice would be limited to advising on laws that distinctively concern Indigenous issues such as land rights, native title, cultural heritage, Indigenous language or laws that are special measures for Indigenous peoples. For Indigenous leaders and Labor this is a major policy and political retreat. It is a different, far more limited conception of the voice – but designed to win conservative and bipartisan support and be carried at a referendum.

A similar argument with some technical differences has been advanced by barrister Louise Clegg in her recent address to the Sydney Institute – she argued it is possible to reconcile a voice with conservative constitutional principles. But Clegg, like Brennan, argues the critical decision must be made – the voice “either applies to laws and policies of general application or it does not”. She says the current thinking on the voice “overcorrects and overreaches”.

The problem with Albanese’s floated proposal is that the scope of the voice is open-ended and unlimited. It can give advice to parliament on bills and to the executive on ministerial decision-making. It can make representations on virtually anything since most laws on welfare, education, tax and health affect some Indigenous peoples. Once the general application of the voice is assumed, it will be a brave parliament that legislates to restrict it.

Brennan and Clegg believe a more restricted voice is essential for success. The issue for the Coalition, therefore, is whether there is a conservative design of the voice that it could accept and over which it could negotiate in the referendum prelude – or whether it takes the inevitable decision to oppose the voice. That would, no doubt, sink the referendum but hardly advance the standing and appeal of the Coalition parties at a time of their historic weakness.

If the Liberals defined the type of voice they would accept, the debate would be different and the Liberals would have far more legitimacy if they eventually decided to oppose the Labor model.

What will Albanese do if the referendum fails? He would probably legislate the voice anyway. He would have the numbers to get the voice through the parliament. Remember, there were initially many advocates saying the voice should be legislated before being put to a referendum. The point for the Coalition is this issue won’t easily die.

The point for Albanese and the Indigenous leaders is whether they care enough about bipartisanship to make concessions to secure it – or whether they think Howard, Turnbull and Brennan are wrong in prioritising bipartisanship. There is a huge responsibility on Albanese: is he willing to put a proposal that constitutes a major change without bipartisan support?

The prospects for Coalition support of the voice are ominous, with John Howard warning of its risks and Malcolm Turnbull, despite becoming a supporter, saying there are “powerful and legitimate arguments” against the voice and that it is a greater constitutional change than the republic.