The American comedian’s funniest one-liner and arguably the funniest of all time was uttered in a stand-up routine where Dangerfield regaled the audience with a tale of improbable woe when performing at another club, this one seedy and at the wrong end of town. “It was a rough joint, I tell ya. A real rough joint.”

One can almost hear the audience chant in reply, “How rough was it?” Then the punchline dropped. “It was so rough the bistro was serving broken legs of lamb.”

Boom-tish – but when it comes to broken legs, Tyson has a story to tell.

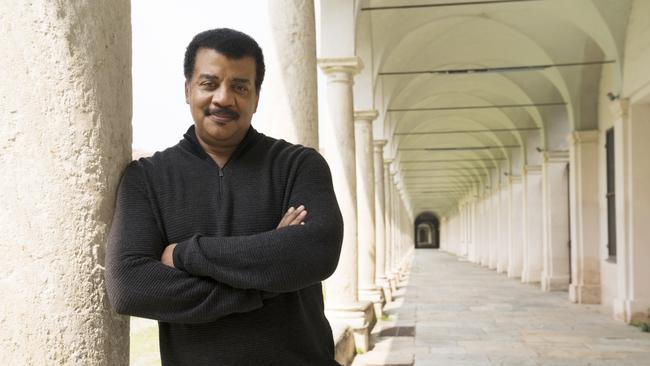

On Tuesday, in one of his many social media forays, the man described by People magazine as the Sexiest Astrophysicist Alive cited an anecdote from cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead.

Tyson told the tale of a student asking Mead to identify the first sign of human civilisation in a culture. Was it the use of tools, of language, or rudimentary law?

Mead is said to have replied that the first evidence of civilisation was the fossilised remains of a fractured and repaired femur found in an archaeological site.

The story goes that Mead went on to explain that a human being with a broken leg 15,000 years ago was a dead man or woman limping, not long for this world. It was death by infection or being served up as a light supper for a long list of apex predators. Yet these fossilised remains revealed someone had cared for this person, healed them and kept them out of harm’s way.

The Mead yarn had been reprised many times before Tyson’s storytelling.

A column in Forbes in 2020 also cited Mead’s broken leg musing.

The author, who was immunocompromised, was preparing for a lengthy stretch of solitude as the pandemic wreaked havoc in New York. She remained cautiously optimistic and would get by, thanks to the immutable kindness of strangers and friends alike. It was the mark of civilised humanity after all.

There is just one problem with the Mead anecdote. It didn’t happen, or at least there is no record of it.

Mead did talk about civilisation and its characteristics in a book, published in 1968, entitled Interviews with Social Scientists, where she offered a much less controversial definition of human civilisation. “We have called societies civilisations when they have had great cities, elaborate division of labour, some form of keeping records. These are the things that have made civilisation.”

Misinformation comes in all shapes and sizes. Quite often it comes in the form of feel-good stories such as this one. Who wouldn’t want to be told they belong to a species whose unique characteristics are altruism and benevolence?

Lost in the fuzzy sentimentalism is the fact animals show empathy and compassion. We see it in our household pets daily.

On firmer ground in an analysis of the canine world, Tyson proclaimed dogs as the most joyous creatures on the planet. They care for us, guard us and miss us when we leave. If my dog could use a mobile phone, every time I would go out to grab a few items at the supermarket I figure my phone would scream that I had 28 missed calls.

We know, too, that chimpanzees apply insects or plants as a form of wound dressing to their companions. Threaten the safety of an elephant calf in front of the maternal herd and see what happens.

Obviously, empathy is not peculiar to humans, civilised or otherwise.

The most obvious gap in the myth-making is the question of how that ancient femur was broken in the first place.

A trip and fall accident is a possibility, but just as likely is that the bone snapped as a result of interpersonal or intertribal violence. Even sexy astrophysicists should dwell on the fact that for every rare archaeological find of a bone mended by human intervention, there are thousands of osseous relics of human skulls caved in with blunt objects.

The cultural traits of human civilisation show humanity in all its rancorous splendour.

Humanity runs the spectrum of the good, the bad and the ugly.

The history of human civilisation reveals internecine conflicts, war and mayhem grounded in tribalism or its contemporary expression in nationalism, sprinkled with random acts of kindness and courage.

It’s a rough joint, I tell ya. A real rough joint.

Neil deGrasse Tyson is not my ideal muse. It’s not that he’s uninteresting. The astrophysicist is a virtual walking continent of insight and intelligence, but where true wisdom is needed I prefer to look to Rodney Dangerfield.