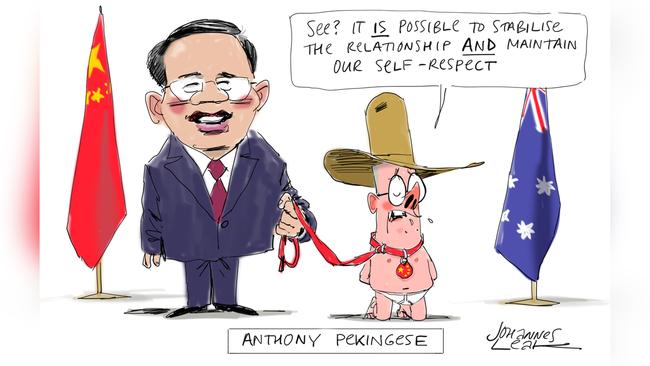

China has turned from wolf to panda for Li Qiang’s visit, but Anthony Albanese must be wary

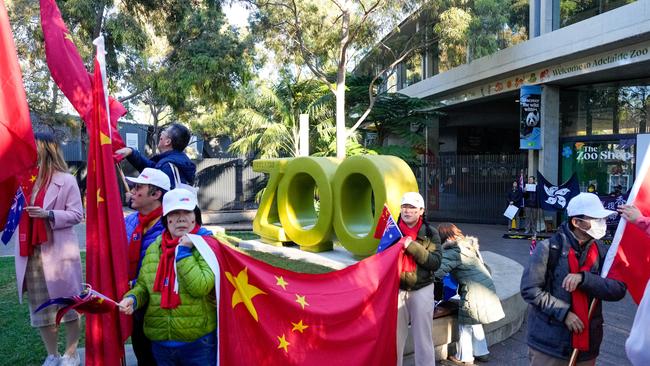

As protesters shouted nearby, the Adelaide Zoo’s male giant panda, Wang Wang, lumbered out into the open to see what all the fuss was about. His platonic enclosure mate, Fu Ni, was nowhere to be seen.

Just a few years ago, Australia was subjected to the full force of China’s so-called “wolf warrior” diplomacy, which petered out as Beijing realised the tactic was doing it more harm than good.

China is showing a more cuddly face for Li’s visit – the first by a senior Chinese leader in seven years. As Wang Wang chewed on a piece of bamboo with his back to China’s No. 2 leader, Li confirmed Adelaide would get two new “adorable pandas” to replace its current pair, who have stubbornly refused to produce an offspring in their 15-year stay.

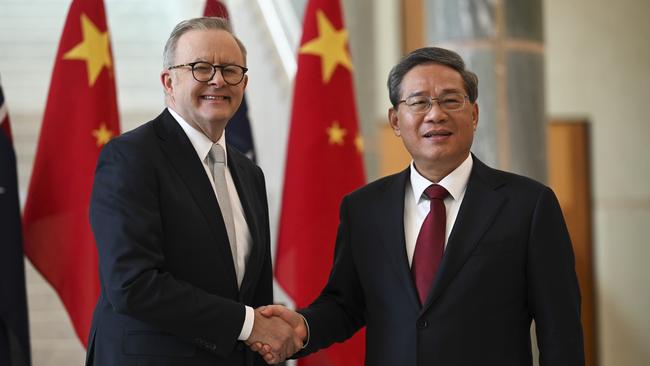

After landing in Adelaide, Li declared the nations’ bilateral relationship was “back on track”.

“China stands ready to work with Australia,” he said. “A more mature, stable and fruitful comprehensive strategic partnership will be a treasure shared by both countries.”

Anthony Albanese will reciprocate, telling a state lunch for Li in Canberra on Monday that his efforts to reopen engagement with Beijing are already delivering dividends.

“There is much that remains to be done, but it is clear that our nations are making progress in stabilising and rebuilding that crucial dialogue,” he will say.

The soft diplomacy on show stands in contrast to the deep suspicion within the government, the national security establishment and the wider community, about China and its long-term threat to Australian interests.

Australia has so little trust in China that some officials involved in the visit, including in ministerial offices, have been issued with temporary “burner phones” to protect their data from Chinese spies who are assumed to be travelling with Li’s delegation.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong touched on the long-term China challenge in an interview with the ABC’s Insiders, saying Australia was now in “a state of permanent contest in the Pacific”.

She sought to make a political point – that the Coalition “abandoned the field”, opening the door to Beijing across the region. It’s a simplistic charge that fails to take account of the scale and relentlessness of Beijing’s ambition.

Albanese has pledged to raise an array of difficult issues with Li, from the unsafe behaviour of China’s military in international waters and airspace, its threatening behaviour towards Taiwan, and the plight of detained Australians including writer Yang Hengjun, who is languishing in a Chinese jail on a suspended death sentence.

Australia’s concerns will be raised behind closed doors, and will be easily fobbed off by Beijing.

The government would prefer Australians focus on its demonstrable “wins”, particularly the rolling back of China’s trade bans on $20bn worth of our exports.

Trade Minister Don Farrell on Sunday said Australia had “not kowtowed at all” to China to have the sanctions removed, but public opinion continues to harden against China.

A UTS Australia-China Relations Institute poll released last week found fewer Australians (54 per cent) now see the economy as being closely linked to China as they did three years ago (63 per cent).

And half of us believe military conflict with China is a real possibility within three years.

Albanese has wryly declared himself “pro-panda”, welcoming good news on China’s cuddly mammals. He needs to take care or he’ll be viewed as a “panda hugger” at a time when Australians are alert and alarmed about the China challenge.

It was, as the Chinese might say, an inauspicious start to Premier Li Qiang’s visit to Australia.