It is true that the stunt, which seamlessly combined the ludicrous with the repulsive, is merely agitprop’s latest triumph over art – a triumph encouraged by cultural policies that increasingly allocate public funding, including some $10m a year to the STC, on the basis of politics rather than merit.

Given the incentives those policies create, it is scarcely surprising that arts organisations, led by the STC, made such a big deal of endorsing the voice. And it is equally unsurprising that the STC’s directors and major donors, having laid out the red carpet for the politics they like, now find those they dislike entering through the stage door.

There may be an element of justice in the STC reaping what it sowed; but it cannot erase the injustice to Chekhov. In effect, of all the great Russian authors of the 19th century, it was Chekhov who most firmly opposed the confusion between art and propaganda.

Writing at a time when incessant political agitation and revolutionary fanaticism had permeated Russian life, he adamantly rejected the view that writers should tell the public what to think, much less dispense public lessons in morality.

His reluctance to assume that role was strengthened by his disdain for the intelligentsia – a term coined in Russia in 1860 – and notably for its “progressive” mainstays.

Even before Chekhov burst on to the scene, the “intelligents”, as they were known, had done everything they could to impose a stifling intellectual conformity. Nikolay Dobrolyubov, a revolutionary writer greatly admired by Marx, Lenin and Stalin, was not exaggerating when he boasted that “today even those who dislike progressive ideas must pretend to like them to gain admission to decent society”.

This “second censorship”, which prescribed what had to be said, was, Chekhov argued, even more oppressive than the “first censorship” imposed by tsars, which merely forbade, rather haphazardly, speech considered especially dangerous.

Dismissing the “molluscs we call the intelligentsia”, Chekhov presciently warned that should they ever seize power, “these toads and crocodiles will, under the banner of science, art and free-thinking, rule in ways not known even at the time of the inquisition in Spain”.

Rather than being bullied into toeing the “progressive” line, Chekhov described creators’ duties as two-fold. The first was intellectual humility: “it is simply dishonest”, he wrote, “to pronounce on issues one scarcely understands”.

The second was to refrain from histrionics, instead setting out, “like a reporter”, exactly what one saw, and “allowing the jury, ie, the public, to do the evaluating”. Accused by the radical poet Aleksey Pleshcheyev of being insufficiently “tendentious” (a characteristic the revolutionaries regarded as a virtue), he replied that “far from not protesting, I protest constantly against lies – is that not a tendency?”.

The supreme value for Chekhov was consequently truth, which he wrote about in terms of “pravda”, a Russian word connoting both justice (“rightness” in a moral sense) and truth (“rightness” as factual correctness). And a truth to which he was strongly committed was European civilisation’s contribution to human progress.

Both Dostoevsky and Tolstoy considered Western Europe, and notably England, the very image of hell. But Chekhov’s letters eulogise its great assets: respect for others, political moderation, freedom under law.

Repelled by the unchecked cruelty of “Asiaticness”, he argued that “the Englishman exploits Hindus, but he gives them roads, aqueducts, museums, Christianity”: the other exploiters, including the Russian empire, only gave back “brutal officialdom and blind obedience”, condemning the people they subjugated to perpetual barbarism.

There was, however, one virtue that figured ever more centrally in Chekhov’s mind as he entered the final part of his tragically short life: toleration. And prominent in his commitment to toleration was his unbending opposition to anti-Semitism.

Born in an area of southern Russia where Jews were allowed to settle, and being himself – as the grandson of serfs – an outsider, he formed lifelong friendships with Jews that would have been unthinkable to writers from Russia’s north. His early work featured some typical anti-Semitic tropes; he abandoned them once the pogroms got under way.

Already apparent in his first major play, Ivanov, the condemnation of anti-Semitism became a crucial part of his outlook during the Dreyfus Affair, which spurred him – for the first and only time – into political activity. Indeed, when his greatest supporter and close friend, publishing magnate and theatrical empresario Aleksei Sergeevich Suvorin, published an anti-Semitic attack on Dreyfus, he terminated their relationship, never to be resumed.

Better than just about anyone else, Chekhov had a gnawing fear of where anti-Semitism would lead – a foreboding that hangs over the final scene of his last and greatest play, The Cherry Orchard, in which the music of the Jewish orchestra abruptly stops, to be replaced by a discordant, frightened jangling that hauntingly presages the horrors that lay ahead.

But although Chekhov is often compared to Samuel Beckett, he did not share Beckett’s pessimism. Waiting for Godot ends with Vladimir and Estragon frozen on the stage, unable to take the next step; in Chekhov, the need to move on, to do what must be done, is always acted upon, even in The Cherry Orchard.

Yes, the future is unpredictable – that is the price of freedom – and (as he put it in The Duel) “when people seek truth, suffering, mistakes and world weariness invariably throw them back”. But regardless of the setbacks, mankind’s “passion for the truth and stubborn willpower drive them forward”, so that armed with what truth they can find, “they will, though I will not live to see it, undoubtedly create another and better life for themselves.”

It is that unshakeable humanism that needs to resonate with us in these difficult times. It will resonate on Friday, more loudly than ever, in Israel as Hanukkah – the festival of lights, which celebrates the triumph of faith and hope over bondage – gets under way.

But it is miles apart from the grandstanding of the actors who – by endorsing Hamas’s Jew-hating death cult – displayed their complete contempt for everything Chekhov held dear. Ignorant of the Middle East’s complexities, disrespectful of their audience, and clearly knowing nothing about Chekhov, they deserve to be fired, not for their views but for their arrogance and stupidity.

Of course, having commented bitingly in his correspondence on “the egotism and obtuseness of actors, not to mention their incompetence”, their gesture would probably have left Chekhov more disappointed than surprised.

This much, however, is certain. In a hundred years’ time, they will be utterly forgotten, as will their sophomoric antics. But Chekhov, and the values he stood for, will be treasured by all those who cherish the magic of words, the beauty of life and the hope of a better future.

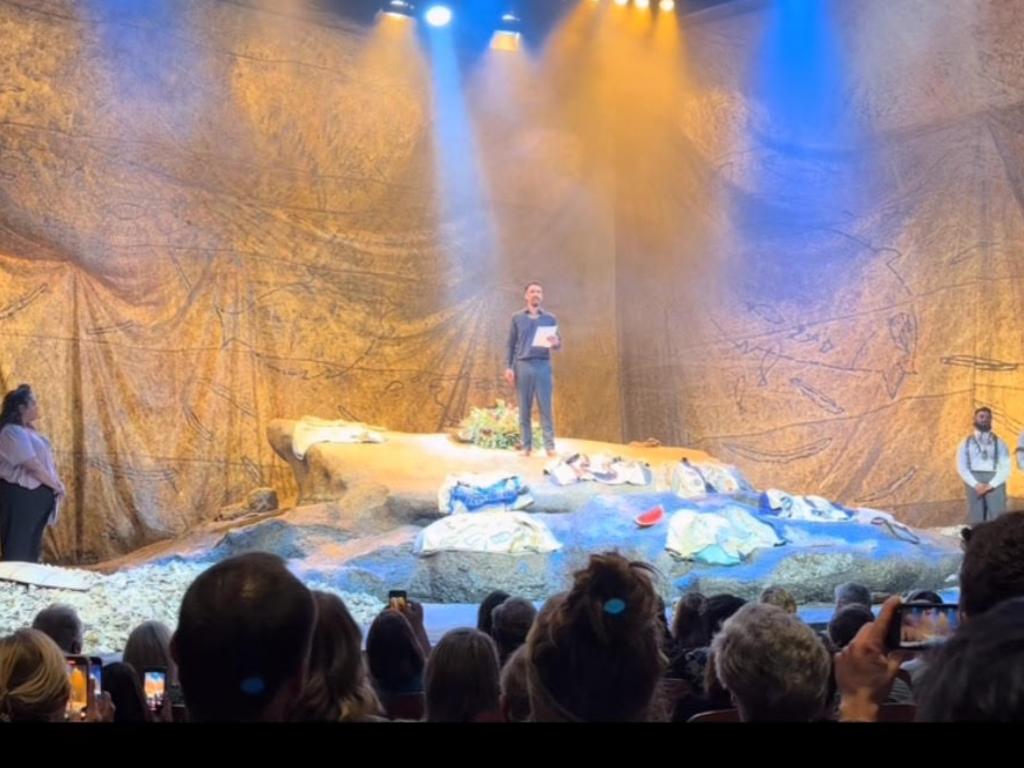

Pity poor Chekhov. It is hard to think of anything that would have appalled him more than actors ending the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of The Seagull by donning keffiyehs in protest at the “occupation” of and “genocide” in Gaza.