Chalmers steering us toward a soft landing in the economic slow lane

Chalmers offered up a melange of self-congratulation, wishful thinking and economic confusion. He compared his budget repair credentials favourably to John Howard’s and boasted he had achieved more productivity reform in two years than the Coalition in a decade. Not only do these claims not withstand the slightest scrutiny, they are either misleading or plainly false.

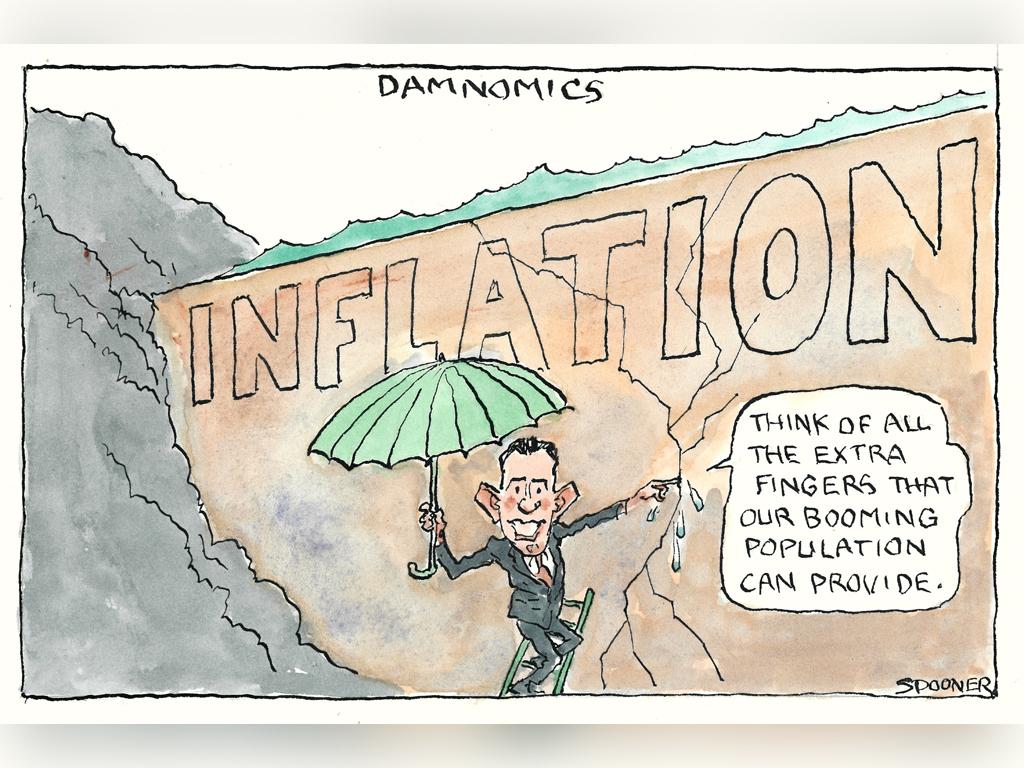

While it is true Chalmers has presided over two budget surpluses delivered by a combination of high commodity prices, Covid-era spending programs expiring and rampant bracket creep (where, as a result of higher nominal wages, more of people’s incomes are taxed at higher rates). Chalmers did not have to lift a finger to achieve this. While Peter Costello and Paul Keating were prepared to cut deeply into spending to strengthen the bottom line, Chalmers (in the 2023-24 and 2024-25 budgets) is raising it by 1.9 per cent of GDP.

Bracket creep occurs by automatic pilot, funded (at a time of falling or stagnant real wages) by making taxpayers poorer. It has helped the RBA in its inflation fight, but fails every test of good policy. Bracket creep is opaque (not explicitly approved by parliament), highly regressive, destroys incentives to work and save, and reduces pressure on governments to keep spending in check, which is why many OECD countries, including the US and Canada, do not tolerate it (they index personal tax thresholds for inflation).

If we lift our sights beyond the past two years, it is clear Chalmers is putting the nation’s finances in a far worse, not better, position. Once recent windfall revenue gains fall away, we are left with medium-term spending stuck at historically high levels as a proportion of the economy (at 26 per cent of GDP, which leaving aside Covid was last recorded during the deep recession of the early 1990s), the gradual ratcheting up of tax burdens (more than 26 per cent of GDP by 2033-34; not recorded since 1986-87), and a string of future deficits.

And these projections are wildly optimistic, assuming the NDIS’s runaway costs can be brought to heel without painful reform (which, despite its talk, the government has shown no willingness to tackle), the shrinking proportion of working-age Australians will happily pay ever more income tax, and no conceivable global economic and security crisis in the next decade.

This is not the worst of it. When he discusses the supply side of the economy, Chalmers claims black is white. He sings the praises of the government’s productivity reform agenda, yet displays a complete misunderstanding of this critical concept.

Chalmers cites the government’s $13.7bn in production tax incentives for green hydrogen and critical minerals. He talks about “getting more capital to flow into” renewable energy and selected net-zero “heavy industries”, the $32bn being committed to housing and another $120bn to infrastructure. And in the best union tradition, he hails the fact wages are “growing at rates not seen in 15 years”. On each front, production, investment and wages, Chalmers is fundamentally wrong.

Indeed, rather than set us up for sustained growth and higher living standards, the Albanese government has gone out of its way to hobble the supply side of the economy.

Its renewables-or-bust net-zero agenda is saddling us with a more expensive and less reliable electricity grid, arguably the biggest self-imposed negative supply shock in our history. Its union-dictated workplace relations agenda, with multi-enterprise bargaining at its core, will profoundly undermine competition in the economy (as large firms cosy up to unions to impose inefficient work practises on new competitors) and raise the structural rate of unemployment. And to top it off, there is the back-to-the-future protectionism of A Future Made in Australia.

One thing is more certain. If we do get Chalmers’ hoped-for “soft landing on a narrow runway”, his economic policy agenda is likely to condemn us for many years to the economic slow lane. Low, supply-constrained growth, higher structural unemployment, continued energy price increases, more economic volatility and a constant risk of inflation breakouts. This economic pain will not be felt in our affluent suburbs, but among working people.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

No doubt frustrated by the negative reception the budget received, Jim Chalmers gave a speech last week on the government’s economic agenda entitled “A soft landing on a narrow runway”. Those looking for frankness about the economic and fiscal challenges we face as a community, and the need for difficult choices, would have been disappointed.