Chalmers budget joins conga line of ‘shows about nothing’

Budgets are above all a test of character and policy credibility for the government of the day. With this in mind, the distinction I draw when evaluating them is between substance and style, consequence and superficiality. In budgets of consequence, hard and politically unpalatable decisions must be made. These may be forced on the government, as they were for Bob Hawke and Paul Keating in the late 1980s as the terms of trade collapsed. Or they may be embraced, as they were by John Howard and Peter Costello in the late 1990s.

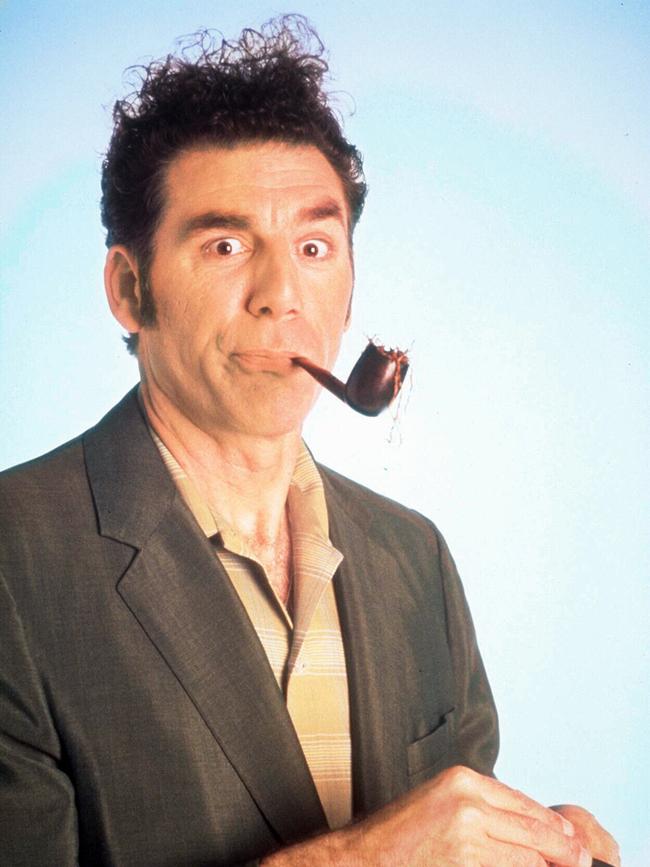

In budgets of style over substance – let’s call them Seinfeld budgets (“a show about nothing”) – while headline numbers give the impression of prudence, no politically life-threatening decisions have been made. Revenues swell automatically as commodity prices surge and, as we’ve seen in recent years, taxpayers are hit by bracket creep. Treasurers who deliver budgets of consequence put their political lives on the line.

Treasurers who deliver Seinfeld budgets do not risk a thing, at least immediately. They get to hand out “free gifts”. In recent Australian history, we have only seen Seinfeld budgets. The last attempt at a real budget was Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey’s ill-fated effort in 2014. The unspoken, but clear, bipartisan consensus since then has been to avoid courageous budgets. Scott Morrison, Josh Frydenberg and now Jim Chalmers have followed this script to the letter.

What about the Rudd-Swan budget in 2008 during the global financial crisis and the Morrison-Frydenberg pandemic-era budgets, you might ask? Yes, decisions of consequence were made in these, but they involved no sacrifice of short-term popularity for the governments concerned. The former is remembered for pink batts and new school halls. The latter was necessitated by entirely unnecessary lock-downs. How should we assess this week’s Albanese-Chalmers budget? If we look through the blizzard of numbers, charts and press releases that have been published and dissected, what sort of budget was it?

There is definitely a Seinfeld element. Strong commodity prices and rampaging bracket creep (only partially returned by income tax cuts) have done the budget heavy lifting, delivering a forecast $9.3bn surplus this year. Bracket creep, together with the 13 consecutive interest rate rises since 2022, have squeezed household budgets, helping to ease inflationary pressures. But if we look at the government’s decisions, they undoubtedly work in the other direction. Adding to rather than helping to abate inflation in the short-term and entrenching supply-side rigidities that can only weaken productivity in the medium term.

While rent and energy bill subsidies may reduce measured inflation, they will necessarily increase rather than reduce inflationary pressures. No credible economist would see manipulating the CPI lower in this way as a legitimate anti-inflationary strategy. Who is advising Jim Chalmers to say this?

There is no careful, disciplined focusing of spending in the budget, with every conceivable cause getting a prize. By my quick count, the Budget Overview lists 59 priorities. In a full-employment economy, this extensive list of wage subsidies, handouts and green industry production credits will only bid up the cost of inputs, including labour, and misallocate capital. While the original stage three tax cuts had a legitimate reform intention, the re-jigged one, while politically popular, is pure redistribution.

This budget, like all others, sets great store by the economic forecasts that underpin the forward estimates. In an economy sending mixed signals, with consumer spending softening, unemployment still very low and services price inflation surprising on the upside, why should we attach any significance to these?

You can see the attraction of them for the government. They fit its desired political narrative perfectly: inflation very quickly returning to its target rate (reminding me of George Bush’s mission accomplished blunder on Iraq) and real wages growing again in time for next year’s election. Treasury staff know the budget is a political document from start to finish.

If you want an insight into what Treasury staff think about the forecasts, ignore the numbers and go straight to the downside risks. And no credence should be attached to the forward estimates, even though these estimate larger future deficits. These were intended as a transparency measure, forcing governments to detail the future impact of spending and taxation decisions. But they have become a vehicle for obfuscation. They rely on Panglossian economic forecasts. They count on continued bracket creep and always under-estimate spending growth, with the disastrous NDIS the key case in point.

So no, this budget is not one of consequence. It is no Keating or Costello effort. No lobby group was harmed in the making of it. But nor is it entirely like the modest Seinfeld affairs we have seen in the past. Perhaps it should be described as Seinfeld-like, but with pretension.

We have the ideological, but economically disastrous, commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050. Whereas Gough Whitlam and Jim Cairns had to deal with the inflationary consequences of an OPEC-imposed negative supply shock, Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers are imposing one on the Australian community.

And in response to this folly, we have A Future Made in Australia. Jim Chalmers tells us, with characteristic modesty, that this is a ‘new economic orthodoxy’. But this orthodoxy is not new and nor is it economics. It is a rehash of pre-Adam Smith protectionism, no more. Paul Keating’s studied silence on this is deafening.

No, budgets are not all the same. And nor are treasurers. While I am critical of Chalmers, to be fair he is no worse – apart from his claim to have reinvented economics – than any of his recent predecessors.

Sadly, everyone since has been Tiny Tim with his ukulele. Occupying a big stage, to be sure, but not living up to the hype and leaving everyone underwhelmed.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

More Coverage

If Keating at his best was Placido Domingo, Costello was not far behind. Both commanded the budget night parliament, both brought spending ministers to heel, and both dismantled the arguments of special interests with wit and verve.

If Keating at his best was Placido Domingo, Costello was not far behind. Both commanded the budget night parliament, both brought spending ministers to heel, and both dismantled the arguments of special interests with wit and verve.

Not all budgets are the same. Political partisans claim there are Labor budgets and Liberal budgets. Economists like to describe them as expansionary or contractionary. But I don’t think either distinction gets to the heart of the matter.