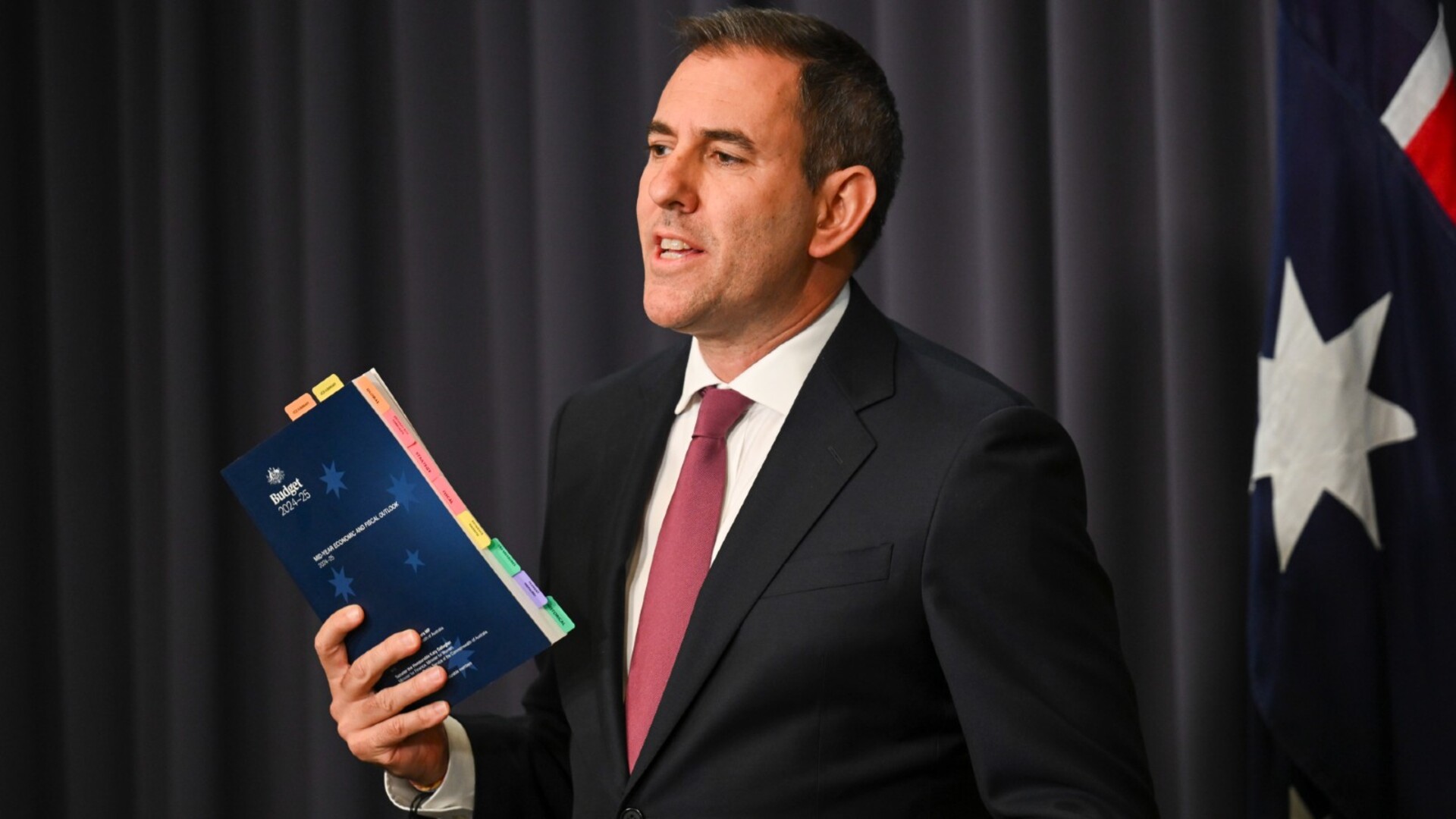

Chalmers refuses to take foot off the spending accelerator

Instead his mid-year economic and fiscal outlook only reinforced the reality that his foot was on the spending accelerator. In the months since the budget was handed down in May, the government’s policy decisions have cost the budget $19.1bn across the forward estimates (offset by only $1.7bn in savings measures).

Higher-than-expected pension, childcare, aged care and other program costs – which the government made no effort to offset – have added a further $4.2bn to this total. As a result, forecast cumulative deficits across the forward estimates have increased by $21.7bn to total $144bn.

While this year’s expected deficit is slightly lower, it’s downhill from there with larger shortfalls to come. If off-budget spending is included – remember the HELP debt giveaway – the picture looks worse: a $90bn increase in red ink, leaving us with cumulative headline deficits amounting to $233bn in the coming four years.

With underlying inflation still well above target in our supply-constrained economy, federal spending will grow by 5.7 per cent in real terms this year, adding fuel to the inflationary fire.

Although the Treasurer conceded on Wednesday that there had been “slippage” in the government’s fiscal position, he pointed to his two surpluses as evidence of progress in “cleaning up” the budget. They are no such thing. The surpluses were the result of our high post-pandemic inflation (and the bracket creep it fuelled), a commodity price boom and high immigration, which boosted revenues well beyond what Treasury expected in its 2022 pre-election economic and fiscal outlook.

Although Chalmers did not spend this windfall (hence the surpluses), he did not have the discipline or foresight to apply any restraint on spending at this time. I cannot think of a single brave spending decision he has made and had to defend. Indeed, he did the opposite, ramping spending up by more than 2 per cent of GDP across the past two years.

When the windfall inevitably receded, we were financially exposed. This is why we have a sizeable structural deficit and no relief in sight. When pressed on the government’s additional spending, Chalmers again invoked the spectre of a “slash and burn austerity budget” that he believes would be “diabolical for an economy barely growing as it is”. This is a misreading of our economic situation.

Chalmers and his advisers appear to believe we inhabit a world of excess productive capacity where government pump-priming saves the day, instead of the supply constrained, full-employment economy we have where public spending is putting pressure on inflation. If he really wanted inflation to come down and help the RBA, he would have used MYEFO to slow the pace of government spending and called on the states and territories to do the same. This would be measured action to address the primary evil our economy faces. It would be responsible economic management.

But with a Treasurer seemingly unable or unwilling to show leadership, the two arms of macroeconomic policy – monetary and fiscal – continue to work at cross purposes, and the government’s energy and industrial relations policies make things only worse.

When assessing the MYEFO, we should not get too carried away by the detailed figures it contains. They represent variations from the budget’s projections, in part because of changes in economic parameters and as a result of government decisions. Yes, it’s unfortunate that future deficits will be somewhat larger, but let’s not forget the government’s 10-year fiscal projections – with its heroic spending and taxation assumptions, most egregiously on NDIS cost growth and heavier tax burdens for middle-income Australians – are pure fantasy.

MYEFOs are intended to hold governments to account for their fiscal targets. But Chalmers has dropped any ambition to balance the budget, having been spooked by Wayne Swan’s failure to deliver a surplus despite announcing four of them in 2012. There is little sign Chalmers is getting sound advice from his Treasury secretary, Steven Kennedy, at this critical time.

In March 2007, Treasury secretary Ken Henry told us in an all-staff address (subsequently leaked) to be vigilant about bad government policies in the lead-up to an election. He rubbished Howard government claims that in a full-employment economy public spending created jobs, pointing out that they only destroyed jobs in other industries. Someone needs to tell Chalmers.

I have written before about the eerie parallels between the Whitlam and Albanese governments. Chalmers reminds me of Jim Cairns, a fellow dreamer and would-be philosopher who refused to apply the brakes to public spending. He would be better served taking a leaf out of Bill Hayden’s book. Hayden became treasurer in June 1975, months before the Whitlam government was dismissed, yet had the courage to deliver a budget the country sorely needed. In one stroke he demolished the Keynesian dogma that had captured the Labor Party in the post-World War II era.

“We are no longer operating in that simple Keynesian world in which some reduction in unemployment could, apparently, always be purchased at the cost of some more inflation,” he said in his budget speech, adding: “Today, it is inflation itself which is the central policy problem.”

Hayden rejected passing the inflation-fighting buck to the RBA, accepting that Canberra needed to take the lead with a budget focused on “consolidation and restraint rather than further expansion of the public sector”. While his efforts were too late to save the Whitlam government, he emerged with his reputation intact, later becoming leader of the federal parliamentary party.

Chalmers undoubtedly has the leadership baton in his knapsack but doesn’t seem to understand that it must be earned by actions rather than words; leadership rather than commentary.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

Jim Chalmers had a golden opportunity on Wednesday to bring fiscal policy to bear in the fight against inflation, taking pressure off interest rates.