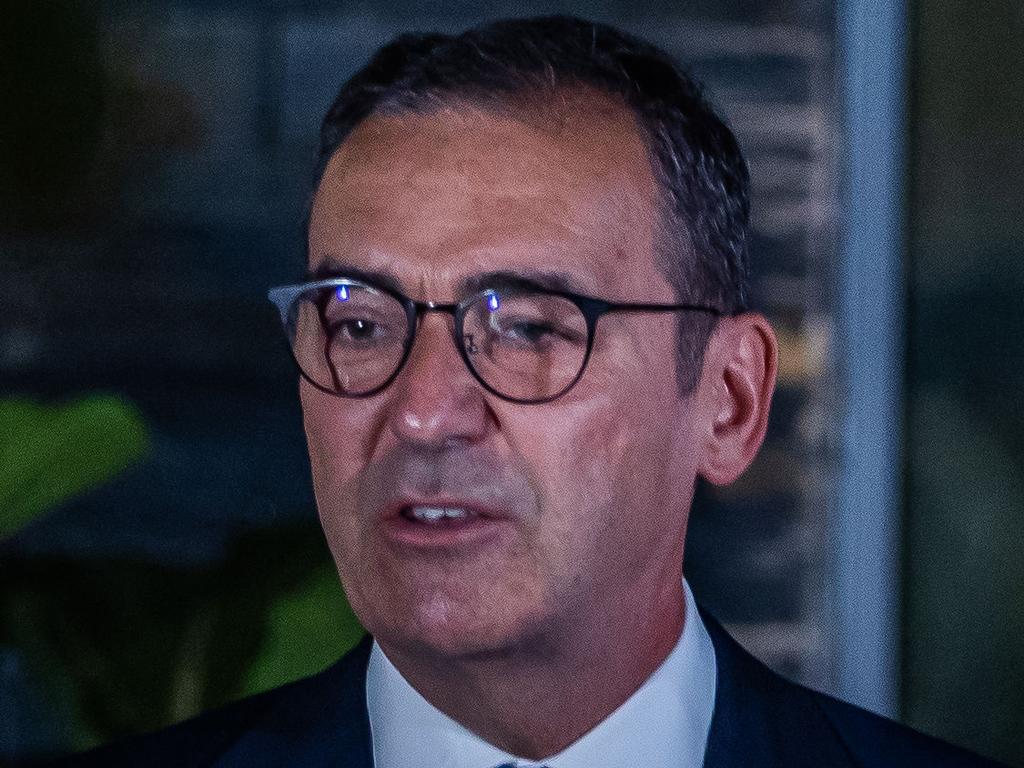

Care and craft announce a new political orator in Peter Malinauskas

I remember Bill O’Reilly (of all people) and American journalist Brit Hume on Fox News saying at the Democratic Convention in 2004 in the lead-up to the Bush/Kerry election, “Who is that guy?”, when they heard the address by a young Senate candidate from Illinois called Barack Obama.

We’ve heard the great Churchill speeches and those of Martin Luther King; we remember the honeyed voice of Bill Clinton. Just recently we’ve heard the eloquence born of dire emergency from the mouth of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Most of the time we live without it. Then like a strange overshadowing of mere politics you hear a speech like the one Peter Malinauskas gave when he became premier-elect of South Australia on Saturday night. It was mild, it was modulated, it had perfect pitch and at the same time it displayed the tradition of classical rhetoric – not in order to showcase verbiage but to sound the resonance of a deeper truth.

The Labor premier-elect did not come out with a perfunctory reference to Indigenous Australians. Instead, he said, “I stand with my feet firmly on the land of the Kaurna people”, and the effect was thrilling because it gave such weight to what could so easily have been the cliche of tokenism.

Then there was the technique of projecting the hope of how history might memorialise what we had cherished and what we had dreamt of. “When we look back at this moment in 20 years’ time, let them say that this generation was the generation“ that achieved change and reconstruction, the premier-elect announced.

And “Let them say”, Malinauskas kept saying with a mounting, flawlessly controlled momentum, marshalling the technique of a tradition that was, by powerful implication, being invoked. And the vision that went along with the eloquence was every bit as lofty as the shaping of the words.

“Let them say in this moment, this most unique of occasions, that this generation decided not just to think about the next four years, but for the next generation, to live out that truly egalitarian Australian ideal, that we care for others more than we care for ourselves.”

Let them say that indeed if we are capable of living up to that ideal that underlies our civilisation, those apprehensions of spirituality and love and mercy that we normally blink away from in the context of the rough-house cynicism of Australian politics.

But Peter Malinauskas’s medium, his care with and command of language, was at one with his message. He talked of how a “successful political party can confuse the elation of electoral success with an inflated sense of achievement”. And he controlled that “elated” audience like a great actor, a great ringmaster. He would have no jeering at his opponents, at the Liberal Party of Steven Marshall, who had proved to lead a one-term government.

“I would also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the Liberal Party of Australia,” Malinauskas said. “The Liberal Party … is an essential component of our federation. It’s a central component of our democratic process and I take this opportunity … I take this opportunity, to acknowledge that the Liberal Party are not our enemies. They may be our adversary, but they are not our enemies.”

Bob Menzies and Ben Chifley, Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke, Paul Keating and John Howard, all acknowledged this bipartisanship on occasion, by implication. But when has an Australian political leader at the very moment of triumph spoken of his political opponents with such grace and magnanimity?

Peter Malinauskas hailed the doctors, the nurses, the hospital orderlies and the ambos, and he did it with a deliberateness that never for a moment denied their particularity and the fact they were special.

It was a superb performance by a magnetic politician and it sent a shiver through sceptical media whose natural stance in the face of political speechmaking tends to be, “Oh, yeah”.

What they thought instead, when they saw and heard Malinauskas ride that ebullient South Australian Labor crowd as a great horseman rides a tempestuous stallion, was: If he can do this in South Australia, what might he not do on the national stage?

When was the last time you heard a great speech by an Australian politician? Paul Keating’s Redfern speech? His Unknown Soldier speech? It’s hard to forget John Howard’s resolve over the guns after Port Arthur, or his decision to go into East Timor.

At some level the Malinauskas rhetoric is about a mastery of technique, but it also shows a political intelligence that is not to be denied. And in this world of bland ukulele playing and accusations about “mean girls”, this very accomplished, very traditional speech reminds us, just for a moment, that we are one of the world’s great democracies.

The other week I heard a friend who had high hopes for Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese say by way of a caveat, “he makes Bill Shorten sound like John F. Kennedy”. We laugh at our politicians’ lack of eloquence but sometimes the opposite is true, they can have strange powers of speech.