Cancel mob thirst for stolen status, not social justice

That editor has since handed in his resignation. And the editor-in-chief of JAMA, Howard Bauchner, has been placed on administrative leave. Why? Because an outrage mob led by Twitter activists and a petition signed by more than 7000 people demanded their heads.

Such episodes are known colloquially as “cancel culture”.

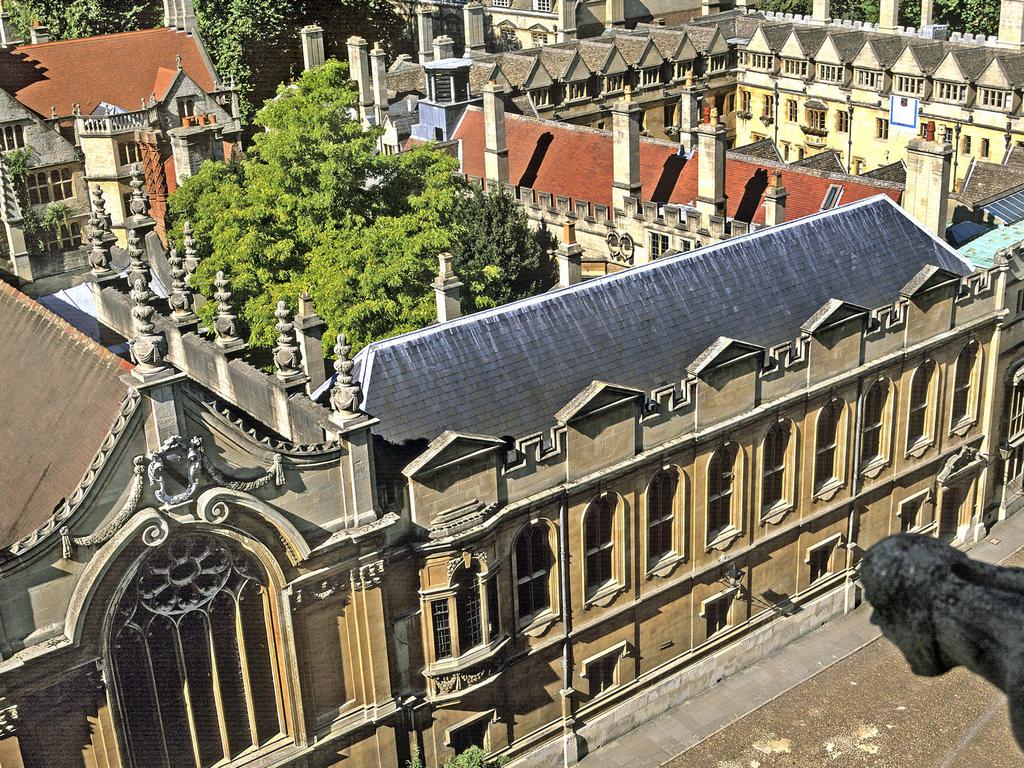

And while cancel culture’s ground zero is the US, America’s cultural power is ensuring this revolution is spreading beyond its borders.

I’m often asked to comment on the phenomenon because the magazine I founded has documented many cases of cancel culture over the past five years — before we even had a term for it. (Our first anthology is called Panics and Persecutions: 20 Quillette Tales of Excommunication in the Digital Age.)

Over the years, the patterns of contemporary excommunication have become clearer and more apparent. The first thing to understand about so-called cancel culture is that it is a fight about prestige and who gets to wield it in contemporary society. Those who instigate these crusades are in search of status and seek to take it from those who already have it.

It’s rare that a cancel culture crusade would target a person in prison, or a patient in a psychiatric institution, or an individual in drug rehabilitation for saying something transphobic, racist or sexist. Those at the bottom of society are immune to cancel culture not because they are morally perfect, but because they hold no status for the crusaders to covet.

Because cancel culture is inextricably linked to status and its scarcity, we should expect to see it happening inside the most prestigious institutions, targeting people in the most esteemed roles. And that is exactly what we are seeing. The episode at JAMA is a classic case where an eminent medical journal and its editor-in-chief are targeted by junior medical professionals seeking to (metaphorically) scalp their industry elders.

The fault line being navigated here is between the liberal meritocracy of the latter half of the 20th century and a new 21st century victimocracy. Cancel culture is the culture of rich Western children who have developed an uncanny ability to manipulate their elders through claims of being “hurt”, “harmed”, “offended” or “distressed”. Claiming victim status is a shortcut when hard work and merit — being unusually talented, skilled, or displaying mastery in a particular area — is considered too onerous a requirement to claim social rank.

This wouldn’t be such a problem and these tactics wouldn’t be so successful if it weren’t for the fact that many institutional leaders, from small private schools to large corporations, are fundamentally ill-equipped to deal with this new cultural reality.

Leaders who have shown weakness in this area are often baby-boomers who went to university before post-structuralism took root in the humanities. They have little exposure or awareness of the nihilism and relativism that passes for scholarship in many academic departments today. They think of the civil rights movements with nostalgia, without being aware that civil rights movements of the 1960s oriented around liberty, not authority, as today’s anti-racist movements do.

Cancel culture strikes in industries when job losses are imminent, such as in the media or academia, or where government grants for artistic programs are few in number and where the future for young people, particularly those with degrees, is precarious. Cancel culture strikes when young people feel pessimistic about their future, when opportunities that were available to their parents are closed off to them, often through no fault of their own.

Combating victimocracy at the societal level won’t be easy, but organisations can build cultures that are resilient to political agitation and social media mobs. For example, executives receive training in diversity, equity and inclusion as a matter of course in today’s world. Executives also receive training in crisis management. I do not think that it would be too much to ask organisations to invest in training for leaders to become resilient to politicised social media campaigns and activist mobbings.

All organisations, companies, corporations and educational institutions should have clear mission statements, and leaders should be expected to defend their own company’s stated mission, even when (or especially when) under pressure. If a company’s mission is apolitical, leaders should be expected to withstand agitators seeking to disrupt the equilibrium of a workplace for political purposes.

Leaders should also be aware that those behind cancel culture crusades are small in number, and most people — whether they are students, employees or the general public — are much more moderate in their political and ideological beliefs than those activists who whip up outrage online or in the streets.

Thanks to the magnifying impact of social media, cancel culture crusaders have effectively convinced the public that they are larger in number than they really are. But it is always worth remembering that the opinions of crusaders are not representative of the public in general.

Wise leaders keep this in mind, and act accordingly.

Claire Lehmann is founding editor of Quillette.

Last month, Edward Livingston, deputy editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, raised a question on a podcast that many of us would find reasonable. He questioned the usefulness of the term “structural racism” in describing American society, a term which often carries the implication that all white people are, by definition, racist. “Structural racism is an unfortunate term” he said. “Personally, I think taking racism out of the conversation will help. Many people like myself are offended by the implication that we are somehow racist.”