America’s cancel culture is becoming absurd

If you’re triggered by a benign act of Abraham Lincoln from almost 200 years ago, or a line from a Robert Louis Stevenson poem causes ‘hurt’, perhaps the problem is you.

There has been no teaching at Robert Louis Stevenson Elementary School in San Francisco for almost a year. Despite overwhelming evidence of minimal viral risk, teachers’ unions in the city, as in much of the United States, have resisted calls to return to in-person classes.

When students do eventually go back to classes in the city’s Sunset district one of the things they’ll have to learn will be an imminent change of the school’s title. It’s one of 44 that the local education authority recently voted to rename.

While the education commissars haven’t yet decided how to get children back in class, they have decided urgent action is needed to remove from schools the names of those who had “engaged in the subjugation and enslavement of human beings; or who oppressed women, inhibiting societal progress; or whose actions led to genocide; or who otherwise significantly diminished the opportunities of those among us to the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

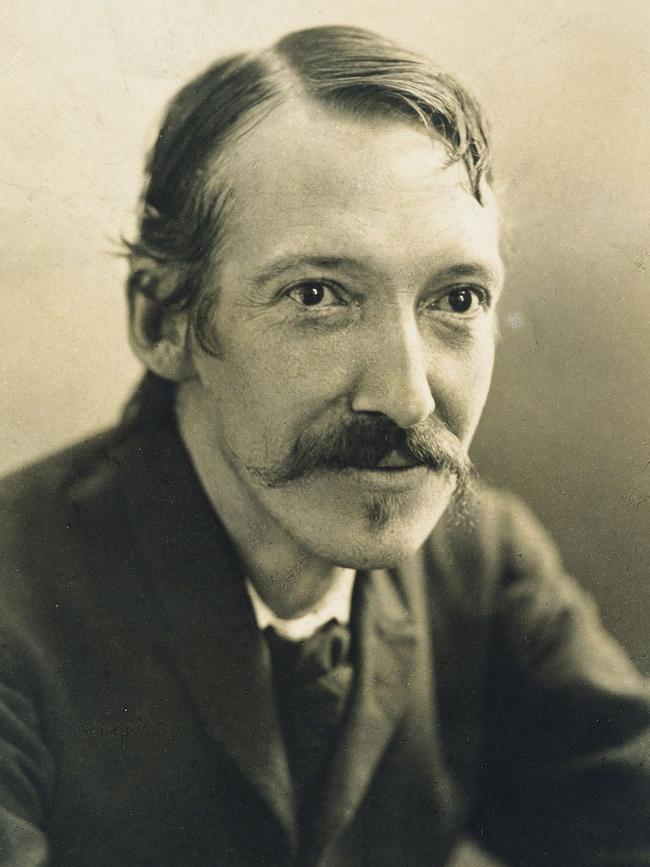

What, you might ask, did the author of Treasure Island and Kidnapped do to diminish the opportunities of San Fransciscans to the right of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? His offence, according to the official record, was to have written a poem called Foreign Children, a bit of doggerel penned from the perspective of a small child in Scotland, musing on how unappealing life must be for children in far-off lands.

If Stevenson had been cancelled for crimes against poetry the decision might have made more sense. Stanzas like “Such a life is very fine,/But it’s not so nice as mine:/You must often, as you trod,/Have wearied not to be abroad” might have made William McGonagall wince. Yet it was described as “cringeworthy” by the authority not on literary grounds but because of its white privileged voice and the use of demeaning ethnic terms such as “little frosty Eskimo”.

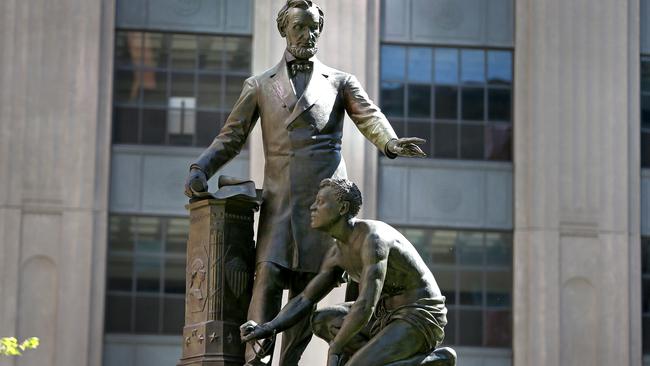

You might agree that a school that honours a children’s author with a Victorian view of the world does irreparable harm to the lives of young Californians, but how about Abraham Lincoln? His name is another of those slated to be removed from a school on the grounds that his policies were “detrimental to … Native peoples of the United States”. That whole freeing the slaves thing evidently didn’t make the cut.

Critics have objected not only to the cultural extremism but the historical ignorance. One decision seems to have been based on a complete misreading of the objective of an expedition led by the revolutionary war hero Paul Revere. Another seems to have confused two people called Sanchez.

If you thought that the disappearance of Donald Trump from the national stage would lower the hysteria about white supremacism in the United States you are very wrong. Last week, a veteran reporter of The New York Times was ushered out the door when the management caved in to pressure from activist reporters.

The reporter, Donald McNeil, had used the ugly racial epithet that begins with “n” and rhymes with “bigger” in a conversation two years ago with a group of high school students. He clearly meant no offence but had simply been asked, in a discussion about hypotheticals, whether he thought use of the word in a particular context had been acceptable.

In asking for details about the context cited he used the word itself.

When management got wind of the incident they reprimanded him but that wasn’t enough for the paper’s staff, 150 of whom wrote a letter to their bosses to say they had suffered “pain” on hearing of the incident. Within a week, the reporter was gone.

This past week, the host of the television series The Bachelor was removed after he refused to condemn a contestant who had taken part in an “Old South-themed” dance several years ago.

Here’s the problem: if you’re going to be triggered by discovering you go to a school named after a children’s novelist who wrote something silly about foreigners 130 years ago; if you’re going to suffer pain because a 67-year-old white colleague used, in an academic, non-confrontational way, a racial slur familiar to everyone who has ever heard a rap song; if you’re so sensitive that you might incur irreparable psychic harm by knowing that a television show is being presented by someone who refused to condemn someone who once got dressed up as an antebellum Southern belle, you might want to consider the possibility that it’s you, rather than they, that are the problem.

What’s more, the extremism of the language, culture and history vigilantes proceeds from a fundamentally demeaning view of the status and agency of minorities. As John McWhorter, professor at Columbia University, one of America’s leading linguists and a black man, has argued, the notion that black people need to be protected from these supposed harms infantilises them.

“In supposing that black people have no resilience, you are saying that black people are unusually weak. You’re saying that we are lesser. You’re saying that we, because of the circumstances of American social history, cannot be treated as adults,” he told National Public Radio last year.

That racism remains a baleful feature of American life is not seriously challenged. But the ideology that insists that black people can only advance by being shielded from the harms of supposed historical and cultural offences is as belittling of them as it is destructive of the unity that all societies need to thrive.

WSJ

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout