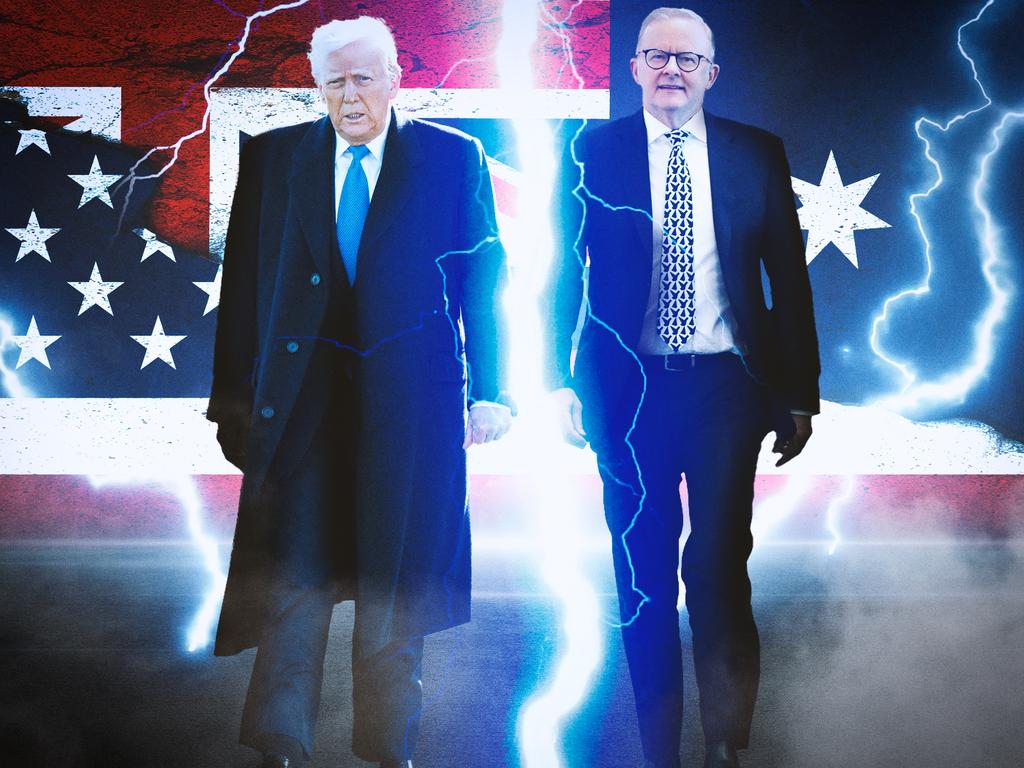

What should the Australian government do about the Trump tariffs? After all, every trading nation on Earth is affected by the world’s largest economy imposing these restrictions on access to its markets.

Well, there was once a time when Australia was a great international trade innovator, setting up the Cairns Group, APEC and nearly 20 free-trade agreements. Today we have taken a back seat in international diplomacy. That’s sad.

Once our election is out of the way, we should become yet again creative and innovative in how free-trading countries can respond to America’s tariffs. The first instinct of the international community is to think that in time America will return to the free-trading regime that has characterised it for the past few decades. The hope is that even if this doesn’t happen during Donald Trump’s presidency, his successor will wind back the tariffs.

This view is very mistaken. There is almost no constituency outside universities and corporate economists in the US for free trade. George W. Bush and Barack Obama were the last two presidents to promote trade liberalisation. Since then both the Republicans and the Democrats have swung hard against free trade.

At the moment the Democratic Party is shifting increasingly to the left as it tries to find a way of winning back working-class constituencies. Among other things, that means protecting traditional manufacturing jobs with high tariffs. So even if the Republicans lose the next presidential election, which is, after all, 3½ years away, don’t expect the incoming Democratic president to be a free trader. We’re stuck with a protectionist America for a long time to come.

It’s easy in Australia to think Trump’s tariffs are unpopular because most of the media writers and reporters dislike Trump and rage against anything he does. But having spent the past couple of weeks in California, my impression is different. There is strong support for tariffs, although not necessarily in the way Trump has applied them.

It’s true there has been a decline in manufacturing in the US, a pattern that began in the 1950s. So there are many Americans who see tariffs as a way to bring manufacturing back home.

Secondly, there is security. Americans understandably feel they have become very vulnerable to supply chains that depend on the economies of adversary countries; above all, China.

They see it is in the interest of American security to onshore sensitive sectors of the economy such as steel, aluminium, pharmaceuticals and healthcare materials. This, it has to be said, is understandable.

And thirdly, there is the revenue. The US government has an eye watering budget deficit of around 7 per cent of GDP or $3 trillion this year. The 10 per cent tariff will bring in something like $200bn a year revenue. Not only will that help reduce the budget deficit but it will give President Trump scope to cut taxes on personal incomes and small businesses.

As a first step, the international community, including Australia, will endeavour to negotiate bilateral agreements with the Americans. That will achieve some success.

The UK and Japan, for example, are President Trump’s favourite nations and he may be prepared to cut quite liberal deals with both of them. Australia should be able to get a better deal for steel and aluminium. But I suspect it will be impossible for us to negotiate away the 10 per cent basic tariff on all imports into the United States.

Over and above that, we could take a lead and encourage the international community to consolidate and expand the existing network of regional trade agreements. We already have the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership with 10 other countries, including Japan, Canada and Mexico. This is a very liberal multilateral agreement and we should give thought to how we can expand it.

Recently, the UK joined this trade agreement, and given that the UK is the fifth-largest economy in the world and Japan the third, the CPTPP will now have very substantial heft. What would make a huge difference to the CPTPP would be if the European Union could be persuaded to join it. We should ask it, and encourage other CPTPP members to join with us.

Given its protectionist instinct, it would be no easy task to get the European Union to accept the terms of the agreement. It would have to abandon almost all of its tariffs relating to trade with members of the CPTPP. It would also have to liberalise its asphyxiating regulations and abandon plans to impose a whole lot of carbon taxes on countries that export to the EU.

But having said that, the EU would gain a great deal out of free trade with some of the fastest-growing economies in the world and it would be a way of compensating for the loss of markets in the United States.

Added to that, it would enhance very substantially the relatively small soft power the EU currently has in the Indo-Pacific. Given the EU and Australia share so many core values, that would be no bad thing.

Whether European leaders have the imagination to do something dramatic like this is very questionable. The EU moves very slowly and plods along on trying to get 27 sovereign states to co-ordinate their positions. But since the UK has been able to negotiate its way into the CPTPP, there’s no reason to believe the EU could not follow suit.

Over and above the EU there is China. China has already applied to join the CPTPP but it doesn’t come close to meeting the liberal trade criteria for entry. What is more, Australia among others would have understandable reservations about committing to a country that in recent years imposed trade sanctions on us for not toeing their line. But still, if China’s diplomacy was smart – and it usually isn’t – then it too would look for a way to get into the CPTPP.

From the Americans’ perspective, they may find the closing of their trading borders will reduce their influence over the international economy.

If other parts of the world opened up their markets the Americans would find themselves left out. And in time that may lure the Americans back into the mainstream of a liberal global trading regime.

The worst geopolitical decision the Americans have made in the Indo-Pacific region was to withdraw from the CPTPP.

If we expand the CPTPP as I suggest, then the Americans may eventually see the benefit of joining it.

Alexander Downer was foreign minister from 1996 to 2007 and high commissioner to the UK from 2014 to 2018. He is chairman of British think tank Policy Exchange.