Blitz on Houthi stronghold raises the stakes for Tehran

It also imposes a cost on some regional economies such as that of Egypt, which is losing money with every ship that no longer passes through the Suez Canal and pays the transit fee due to Cairo. Somewhat perversely, US export sales of its shale oil have boomed following the Houthi campaign of disruption as the oil travels along secure supply chains.

The build-up to this attack has been comprehensive and ordered. Arranging for a multinational naval coalition in the first instance was followed by an open letter signed by more than a dozen nations, including Australia, calling for the Houthis to stop their attacks. The Houthis responded with more attempted attacks.

The final piece in the international puzzle was in place on Wednesday when a UN Security Council resolution called for an immediate halt to all attacks against shipping in the Red Sea. Notably, both China and Russia abstained from rather than vetoed the resolution. Washington had gained diplomatic top cover for a military response.

Washington was keenly aware of the need to ensure any response was calibrated so it was of sufficient weight to impose a real cost and to deter the Houthis from continuing their attacks, while at the same time not being so comprehensive as to leave the US with no room to up the military pressure if this attack was not sufficiently persuasive. One can be certain that in the six weeks since the Houthis began their attacks, Washington has been building up its intelligence picture of Houthi capabilities and their disposition.

Of course, graduated military responses in a region as complex as the Middle East rarely if ever occur along a linear trajectory, so predicting the manner in which response and counter-response will play out is fraught with difficulty. The deterrence effect of a coalition missile and airstrike should also be seen in the context of Yemen’s recent history.

The Houthis have endured years of a Saudi-led air campaign since the start of Riyadh’s ill-fated military intervention in 2015. They are without doubt a tough opponent, having overthrown the long-term Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2014 and then to seize control of the post-Saleh government at the start of 2015. They were then able to fight the much better-resourced and equipped Saudi-led coalition for seven years until a UN-brokered ceasefire came into force in 2022.

But for all their undoubted martial ability, fighting Saleh’s forces and then later the Saudi coalition were products of necessity. They were fighting on their own ground and for their survival either as a movement or as the dominant power in Yemen. It was also in Tehran’s best interests to support the otherwise friendless Houthis against the Saudi-led forces as part of the broader regional rivalry – the Houthis’ Zaydi form of Shi’ism bears little resemblance to Iran’s orthodox Ithna ’Ashari Shi’ism and they should be viewed more as transactional partners than ideological fellow travellers.

The Houthi action in the Red Sea, by contrast, is not a conflict of necessity but a conflict of choice. So it remains to be seen whether they make their cost-benefit calculations in the same way as they have with previous conflicts. To be sure, their actions in attacking shipping in the Red Sea and earning the ire of the West means they can portray themselves as part of a broader regional resistance grouping, and not just a local socio-religious movement vying for power in southern Arabia.

There is a certain attraction in carrying out their anti-US, anti-Israeli actions given the “Death to America, death to Israel” slogan that has been given voice for more than two decades. But to date their maritime capabilities haven’t matched those of their ground forces. They were able to capture one ship and its crew early in the conflict, but their subsequent attempt resulted in the loss of nearly all the attack boats involved and the deaths of 10 of their sailors. They have launched dozens of attack drones, cruise and ballistic missiles but with little effect due largely to the defensive efforts of US, UK and French naval vessels.

For their domestic audience, the Houthis’ continued ability to fire at commercial shipping and claims to be attacking US warships will have some resonance. But the UN Security Council resolution, the Chinese and Russian abstention and the limited effectiveness of the Houthis’ weaponry, and the ability of European trade to bypass the Red Sea, albeit at some financial cost, will give some pause to think about the continued utility of their attacks.

Beijing has diplomatic capital invested in the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, and commercial interests in free passage through the Red Sea. Tehran will not wish to risk putting China offside by allowing the Houthis to escalate the situation too much further, let alone expand it to the Gulf states. Whether they will or can rein in the Houthis will be critical to seeing where this conflict goes next. One thing is for sure, though – things rarely go according to plan in the Middle East.

Rodger Shanahan is a Middle East analyst and former army officer.

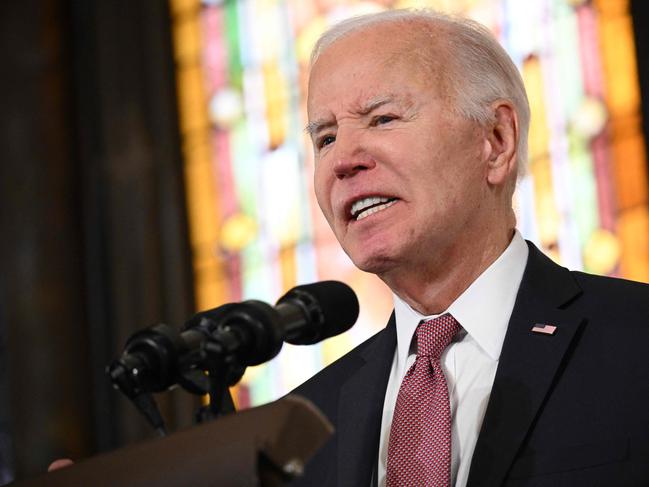

In the end, President Joe Biden was left with no choice but to order a series of significant, but limited, strikes against Houthi military infrastructure and weapons in Yemen. The Houthis’ attacks against merchant shipping in the Red Sea were increasing and imposing a cost on traders as they had to re-route ships around the Cape of Good Hope or pay increased shipping costs for transiting through the Red Sea.