Red Sea warship rebuff: spurious strategic arguments used to hide serious and embarrassing obstacles

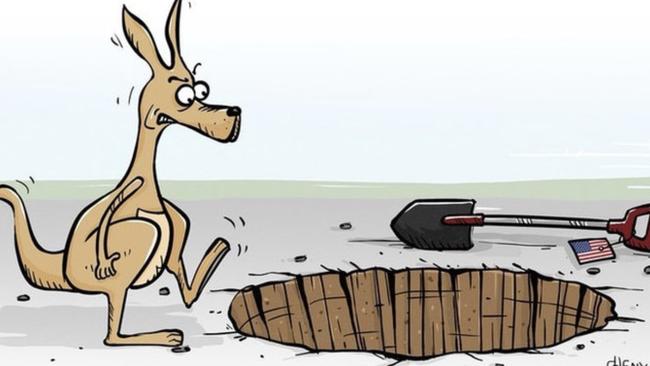

The Albanese government’s fumbling of a US request to send a warship to help protect a global trade route exposed the nation's lacking in naval resources.

The request from Australia’s closest ally was treated from the start with the same enthusiasm one might show an uncle who turned up to Christmas lunch with Covid.

The government did not want to talk about the request, it tried to play it down, it refused for days to give a definitive answer and then it refused to explain properly why it turned decades of alliance tradition upside down by eventually saying no. This secrecy suggests that this clearly unwelcome US Navy request for a warship probably would never have been revealed publicly had The Australian not broken the story of its existence last week.

But the government’s handling of this issue raises more questions than it answers, and none of them is flattering or reassuring.

There are only three potential reasons Australia would say no to a US Navy request to help protect commercial shipping through sea lanes where more than 12 per cent of the world’s trade passes, including many billions of dollars of Australian imports and exports.

The first is that there has been a change in Australia’s strategic priorities to such a degree that we no longer support sending military assets out of our immediate region except in extreme circumstances.

The second is that the navy is so rundown, so inadequately funded, that it does not have a ship, crew or appropriate weapons to be able to muster at short notice a single ship for deployment to a hot war zone in the Middle East.

The third is that the government is wary of alienating Arab and pro-Palestinian voters in Australia by sending a warship to the Middle East when it is stepping up calls for a ceasefire in Gaza and is increasingly critical of Israel’s conduct of its war on Hamas.

According to the limited comments from Anthony Albanese and Defence Minister Richard Marles, the stated reason for the refusal of the US request for a warship was that Australia’s navy was focused on our “immediate region”.

“We need to be really clear around our strategic focus, and our strategic focus is our region – the northeast Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, the East China Sea, the Pacific,” Marles said.

The Prime Minister said Australia’s naval resources “have been prioritised in our region, the Indo-Pacific”.

But Australia also has had a long tradition of sending modest but symbolically important military contributions to distant global hotspots from Afghanistan and Iraq to Somalia and Rwanda.

The proposed Australian naval contribution to the new US-led 10-nation naval taskforce in the Red Sea was not peripheral to Australia’s national interests. On the contrary, the protection of the sea lanes in the Red Sea off Yemen is directly critical to Australia’s trade. The missile and drone strikes on commercial shipping by Iran-backed Houthi rebels protesting against Israel’s attacks on Gaza have already forced major companies such as oil giant BP to take longer, more expensive routes.

As such, Australians will already pay more for petrol and other consumer goods because of Houthi harassment of ships that directly feeds into the cost of transit, but we will pay a far higher price if the trade route becomes unusable.

What’s more, the navy has extensive experience operating in the Middle East, having almost continuously deployed ships there on a rotational basis from 1990 until 2020. During this period there have been 68 deployments of an Australian warship to the region to combat piracy, terrorism and smuggling and to support freedom of navigation. Australia was a founding member of the 39-nation Combined Maritime Force formed in 2002 to help secure the waters of the Middle East. It was this US-led body that requested that Australia provide a warship to the new taskforce set up this week by US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin.

As Jennifer Parker, a naval strategist at the Australian National University’s National Security College, says: “We cannot draw a neat regional bubble around Australia and say that this is where we will operate our ships, blind to our dependence on those long sea lines of communication.”

The government argues its priority naval focus is on Australia’s immediate region, including the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea where Beijing has made illegal territorial claims. But to listen to the government this week, you would think niche military deployments outside Australia’s immediate region are suddenly no longer a part of defence policy.

This is despite the fact the government announced in July it would send a E-7A Wedgetail surveillance aircraft, with up to 100 support crew, to Germany for six months to support Ukraine’s war effort.

This week Marles said: “What comes from the Defence Strategic Review is an urgency around Australia maintaining a strategic focus on our immediate region, and that’s what we’ll do.” He neglected to say the DSR also states a naval deployment such as the Red Sea mission is precisely the sort of mission Australia should undertake in conjunction with its regional responsibilities.

Under the heading Australia’s Strategic Posture, the DSR states: “The defence of Australia’s national interests lies in the protection of our economic connection with the world and the maintenance of the global rules-based order.”

It goes on to say: “Accordingly the ADF must have the capacity to … protect Australia’s economic connection to our region and the world (and) contribute with our partners to the maintenance of the global rules-based order.”

In relation to our closest ally, which requested the warship, the DSR states “the alliance with the US is becoming even more important to Australia” requiring increased “engagement with the US on deterrence, including through joint exercises and patrols”.

The notion that a focus on Australia’s immediate region precludes niche military deployments farther afield is bunkum, according to ANU emeritus professor of strategic studies Paul Dibb. Dibb is the author of the seminal 1986 Dibb report that led to the current Defence of Australia policy, which enshrined the notion that Australia’s defence priorities lay in its immediate region rather than in “forward defence” far from Australia.

“Defence Minister Marles is manipulating the so-called Defence of Australia doctrine and the primacy of our region of primary strategic concern as an excuse,” Dibb tells Inquirer.

“It was never meant to exclude modest contributions to the joint allied effort. He talks with abandon about protecting sea lines of communication elsewhere but seems to ignore the fact that sea lines from the Persian Gulf through to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal are critical for oil supplies.”

Dibb says the timing of Australia’s rejection of the US request for a warship could not have been more embarrassing, coming just days after the US congress passed key legislation to enable the transfer of sensitive nuclear technology required for Australia to procure nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS pact.

“Only days after the US congress had agreed, with qualifications, to sell us three Virginia-class SSNs (nuclear submarines), Canberra looks a gift horse in the mouth and says no to deploying a solitary warship into the Red Sea,” he says. “This is not only highly embarrassing, it is a national disgrace.”

Dibb says the contrast between the strategic timidity of this government and the boldness of previous Labor governments is striking. “In 1991, prime minister (Bob) Hawke agreed to a request from Washington for us to send one of our guided missile frigates (FFG-7s) into the Persian Gulf as the lead warship for the American aircraft carrier battle group,” he says. “This was a potentially highly dangerous mission.”

China was quick to take advantage of the government’s rejection of the US proposal, with its state-run Global Times newspaper lauding Australia for “distancing itself” from its closest ally. The paper linked Australia’s diplomatic break with the US with its recent decision to back a UN resolution for a ceasefire in Gaza with the refusal of the US warship request.

“(Australia) has finally stepped out of the US shadow to call for a ceasefire and could potentially act as a mediator in the conflict if needed,” the paper said. “That opportunity will be lost if it has a military presence in the region. It is sensible for Australia to continue distancing itself from the US.”

It’s no surprise that the opposition has attacked the government’s handling of the issue, with foreign affairs spokesman Simon Birmingham, defence spokesman Andrew Hastie and Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor saying Albanese’s pledge of diplomatic support instead of a warship for the Red Sea mission was “weak and nonsensical”.

Others have speculated that the government’s reluctance to send a warship was fuelled by fears that it would be poorly received by Muslim voters and pro-Palestinian supporters.

No evidence has yet emerged that this was a consideration within the government or that such a deployment would necessarily have triggered a backlash in heavily Muslim Labor seats in western Sydney.

The challenge of safeguarding sea lanes is a separate issue to the war in Gaza, even though the Houthis say they are attacking shipping in protest against Israel’s war on Hamas. But Australia’s position on the Israel-Hamas conflict has been uneven.

Canberra has backed Israel’s right to destroy Hamas but at the same time has backed a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire that could have the effect of leaving Hamas is control in Gaza. The conflict has generated serious tensions here in Australia with large pro-Palestinian protests and a surge in anti-Semitism. Did the government fear that sending a warship to the region at this time would upset its own attempt at policy balance and look too gung-ho, too pro-US and too pro-Israel when it is seeking to wind back its initial full support for Israel?

The almost complete lack of strategic rationale for the refusal of the US warship request suggests the most probable reason for the decision was that Australia was unable to deploy a single warship with a full crew and appropriate weapons at short notice for such a mission, especially over the Christmas period. As Dibb says: “If that is the case, it is also a national disgrace. What are we spending $50bn a year on?”

The government has been secretive about its capability to deploy a ship, but there clearly are several serious obstacles.

The first is that there were few suitable choices of warship available. Only three of the navy’s eight Anzac-class frigates are available for deployment, but these ageing boats have only eight missiles cells, meaning they could quickly run out of firepower given that one US warship shot down 14 Houthi drones in one day last week. They cannot replenish their missile stocks at sea and would need to return home to do so. The Anzacs also are not equipped with counter-drone defences and so would have to fire expensive anti-ship missiles to shoot down cheap Houthi drones.

This meant the only viable option for the government was to send one of its three Hobart-class air warfare destroyers, although one of these returned just last week from a three-month deployment in Asia. These more formidable and modern ships have 48 missile cells, but even they do not have counter-drone defences – an oversight that is astonishing given the rapid growth in drone warfare in recent years.

The navy also was struggling to find enough crew to operate a ship on a long-term deployment to the Middle East. Crew numbers are so low across the navy that one Anzac frigate, HMAS Anzac, has been pulled out of the water indefinitely because there are not enough crew to keep all of the Anzac vessels in service.

These were the parlous naval choices facing the government, but none of these shortcomings can be made public without sparking a withering public backlash. Instead the government has chosen to hide behind spurious strategic arguments that effectively abandon Australia’s proud history as a reliable ally ready to do its small part to contribute to global security. It has not been pretty to watch.

The Albanese government’s ham-fisted rejection of a US Navy request to send a warship to the Red Sea to protect critical global trade routes is one of the most damaging and peculiar episodes in Australian diplomacy for years.