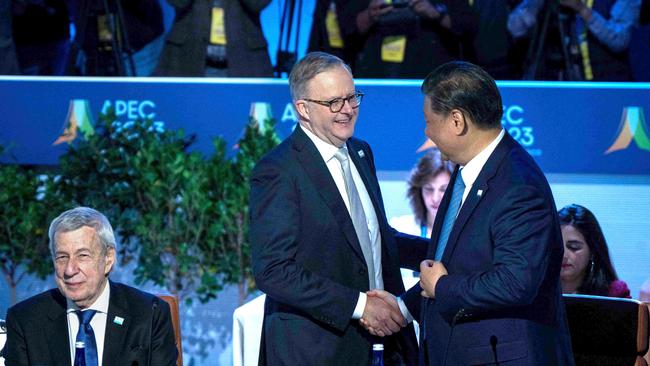

But that’s what happened on Monday when Anthony Albanese replied to Peter Dutton’s question about raising the sonar incident with President Xi Jinping at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation meeting earlier this month.

“You might like to ask yes or no as to whether Cheng Lei thinks that our approach towards diplomatic relations is more effective than yours,” the Prime Minister shot back. “You can talk to her because she is now in Melbourne with her family. With her family.”

I had unwittingly become the story, as opposed to observing and reporting on the story.

I’m a business journalist, and my knowledge of the world of diplomacy was limited, and still is. What I do know is that diplomacy matters, even at a personal level.

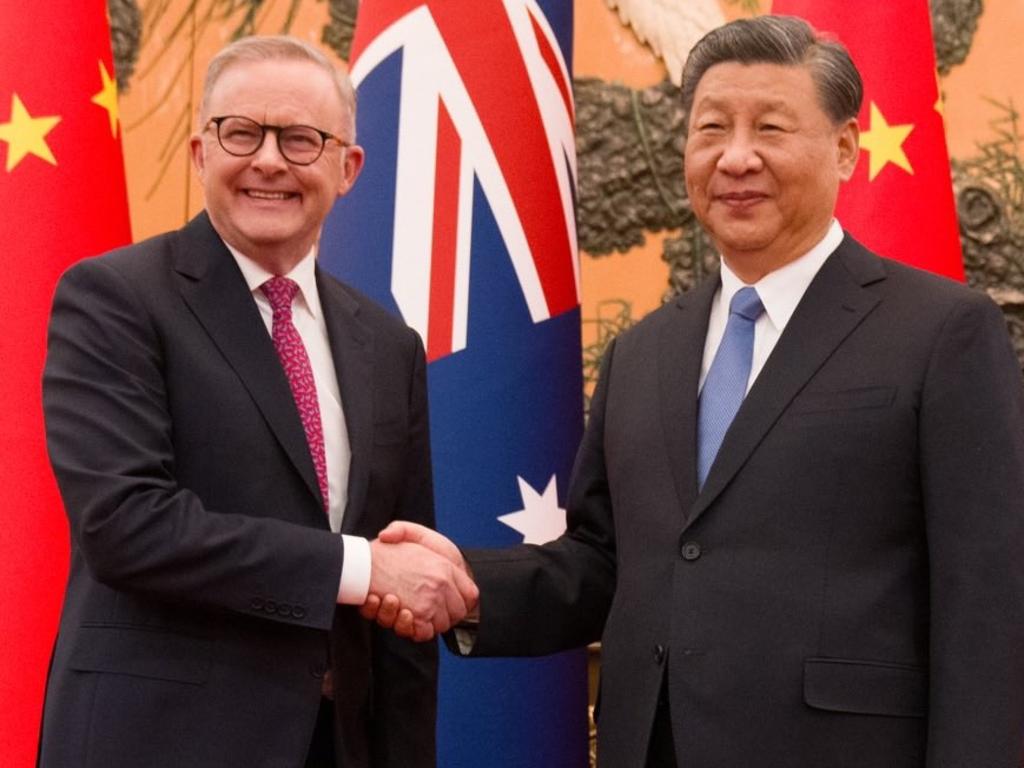

Just 18 days after Albanese and Xi met at the G20 last year, I was granted a phone call with my mum and children, something the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade had been formally requesting for two years without success. In 1154 days of incarceration, that was the only time I heard the laughter of my children.

To be Australian-Chinese is to be almost schizophrenic. I see through each side’s eyes what the other says and often it makes me cringe. On China’s side, thanks to the Great Firewall and the Propaganda Notices (directives for all media on what and how to report), the narrative is tightly controlled.

And you know what happens to people who don’t heed that control. Diplomacy is not for the masses to know about beyond stock phrases. When I was released, great care was taken to divorce the issue from diplomacy lest it be construed as some sort of softening under Australian pressure.

When leaders meet, it is all about painting a picture of welcome, harmony and win-win, never mind wolf warrior style denouncements just days before.

State media coverage of meetings such as APEC and G20 entails interviewing attendees who are China-friendly; obtaining sound bites from the host nation’s China trade/business association; reporting on the latest infrastructure co-operation between China and the host nation; articles on a newly China-invested factory in the host nation with happy workers’ praise; and eliciting a gushing letter from a school in the host nation with a sister school in China

Compare that with Australian media’s questions to Albanese on Joe Biden’s “Dictator” comment and the pressure to answer whether the Prime Minister raised the sonar incident with Xi; the contrast is obvious. Diplomacy that satisfies domestic critics may backfire, as China has discovered with some wolf warrior diplomatic efforts.

So why does China obsess about how it looks on the international stage? China sees itself as having been a doormat in the early 20th century; it carries a chip on its shoulder. “Our spines are tougher now. We’ve taken calcium supplements.” This half-joking phrase, heard among the masses, is a mixture of propaganda rhetoric and heartfelt pride.

We hear a lot about how dealing with China takes a “nuanced” approach. But what does that really mean and how might that apply to recent incidents? It means knowing when, where and how to communicate and, crucially, to whom. It is between hardline and kowtow.

Back to the sonar incident that put our brave servicemen and women in harm’s way. It was dangerous, provocative, unnecessary and unprofessional. But would raising it with Xi at APEC been the best time and place? The relationship has just recovered, there is intense media coverage, it puts the senior leadership on the spot because the incident happened just three days before the meeting. The leader-to-leader meetings are reserved for face-giving and tone-setting; problems are resolved at lower levels before or after. “We set the stage, you perform the opera,” as the Chinese saying goes.

So what is our national interest when it comes to Sino-Australian relations? Results or optics? Help with the polls? Keeping the opposition at bay? Making the headline-hungry media happy?

Australia should and does have principles. But, as with all relationships, to live and die according to principle all the time is unreasonably rigid – you’d clash an awful lot and be quite unpopular. It doesn’t work in families, businesses or politics. The problem with standing solely on principle is twofold. One, you can fail to see things from others’ point of view; and, two, you are never open to the possibility that you might be wrong.

Of course the irony of my calling for nuanced statecraft is not lost on anyone. I was all for more nuanced reporting on China, believing there must be something between a China-basher and a panda-hugger; the China story needed context and texture, which I would contribute. But what happened to me strengthened the case for a hardline attitude because it highlighted China’s regression in citizen freedoms and heightened security paranoia.

The other irony is, when more understanding and engagement would help at a time of complexities and intricacies in the Australia-China relationship and global geopolitics, my case has put people off China. I get it, and cannot disagree. If a business reporter and ordinary mother of two can be put away for more than three years, it does seem scary to go there. That’s sad to see and I do hope for positive reform.

Aussie journalists who would have obtained a better understanding of China’s perspective are now advised to not go. The Aussie audience keen to know more about China will know less. That to me, in the long run, is more disturbing than investigating what channels Australia used to raise concerns with the sonar incident.

Cheng Lei is a journalist and a former detainee in China. This article first appeared on SkyNews.com.au.

It’s not every day you hear your own name raised in parliament – mentioned as a gauge of the effectiveness of Australia’s diplomatic approach to China, no less.