Australia’s soft power reputation is bust. This is the tragedy of our modern politics

Australia was seen, as Peter Costello put it last week, as an exceptional nation. As the foreign minister at that time, everywhere I went, ministers, prime ministers and presidents would ask me about Australia’s policies; Australia was seen as one of the world’s greatest success stories. As a leader.

This boast probably needs some explanation. What was it about Australia that triggered such admiration? Well, first, it was its economic performance. Australia had an economic growth rate of approximately 3.5 per cent, growing productivity, growing per capita incomes and, importantly, growing consumption and business investment.

What’s more, the Australian government ran a budget surplus and had paid off all net government debt. The world wanted to know how Australia had done this and in particular the types of economic reforms we had pursued and how we had done it politically.

Second, Australia had become a significant international player. The world noticed when we helped Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea get through the Asian economic crisis, when we helped end the Bougainville conflict, led the peacekeeping force in East Timor, saved Solomon Islands from civil war and contributed to the War on Terror. Australia also came into its own as a contributor to the geopolitics and economics of the Asia-Pacific region.

We set up the trilateral security dialogue that later became the Quad and negotiated free-trade agreements with the US and a number of Southeast Asian countries, and began similar negotiations with Japan, South Korea and even China. We had been a founder member of APEC and later of the East Asia Summit.

I well remember president George W. Bush and his secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, seeking John Howard’s and my advice on how the US should deal with China. Let’s be frank. Donald Trump won’t be looking for the current Australian government’s advice on China.

And then there was immigration. We had demonstrated we could have a robust and successful immigration program yet deny access to Australia for people who tried to game the system by hiring people-smugglers. The rest of the world – particularly developed countries – were wrestling with low rates of economic growth and wondering how to counter the rise of Islamic terrorism, and couldn’t work out how to address the problem of illegal immigration. Australia had answers to all of those questions. We were a world leader.

But today there is very little international interest in Australia. Australia’s international reputation these days is much more about beaches, unusual marsupials, dangerous spiders and beautiful weather. That was the old picture of Australia before it developed a reputation for being the go-to place to see good policy in action.

This is the tragedy of modern Australia. It has lost its mojo. It’s lost its passion for innovative liberal policymaking and instead replaced it with the policy packages of Europe. We no longer lead the world in policies, we follow Europe.

Let’s take economic policy. Instead of a budget surplus and zero government debt, Australia is doing exactly what the Europeans have been doing: running deficits and building up ever larger government debt.

Debt servicing is growing as a proportion of the national budget and there is no sign that the Australian government has any plans to reverse that. Take investment, too. Australia’s focus, like much of Europe, is on government investment in all kinds of activities, few of which generate a net economic return. The most prominent of these is the renewable energy revolution.

Instead of being a land of cheap energy, which was one of Australia’s comparative advantages, our government now boasts of an ever growing level of renewables – albeit intermittently available – from wind and solar. That’s what the Europeans have been doing.

Like many European countries, Australia has been pouring tens of billions of dollars into subsidising expensive and inefficient energy resources when it’s sitting on some of the cheapest available naturally occurring fossil fuels. Politicians think that by forgoing Australia’s comparative advantage the country will somehow become a renewable superpower. That’s what they all say!

Boris Johnson famously claimed that under his leadership Britain would become the Saudi Arabia of wind power. These sorts of claims are just absurd.

Diverting economic resources into more expensive energy sources and banning cheaper alternatives is designed to reduce global warming. We only export uranium for foreign nuclear power stations but refuse to use it at home! Yet our contribution will have almost no measurable effect at all on the global climate.

I accept we have to make a proportionate contribution to the global effort to reduce CO2 emissions. But we want to go much further, and by going much further we are damaging our economy without making even the slightest contribution to reducing global temperatures.

And then there’s security policy. Australia is no longer in the vanguard of those countries passionately embracing the Western alliance in meeting the many challenges it faces.

We have turned on our most important ally in the Middle East, Israel, during Israel’s greatest moment of need since 1948. Because we have become a half-hearted supporter of the Western alliance, what we say about Ukraine is completely irrelevant and the West barely listens to us any more on the issue of China.

The sad fact is, Australia is losing its soft power in the world because as a country we have lost direction. We have abandoned economic reform and replaced it with a European-style social democratic model of big government spending, almost zero productivity growth, stagnant real living standards and GDP growth that is anaemic.

Whether I’m in the US or Europe, where I spend a lot of my time, no one anymore looks to Australia for any guidance about good policy.

Australia’s political class seems satisfied with this miserable record. They shouldn’t be. They should hang their heads in shame as we come to the end of the year and start to think about how we can rebuild our reputation as a forward-looking, dynamic country that sets an example to the rest of the world.

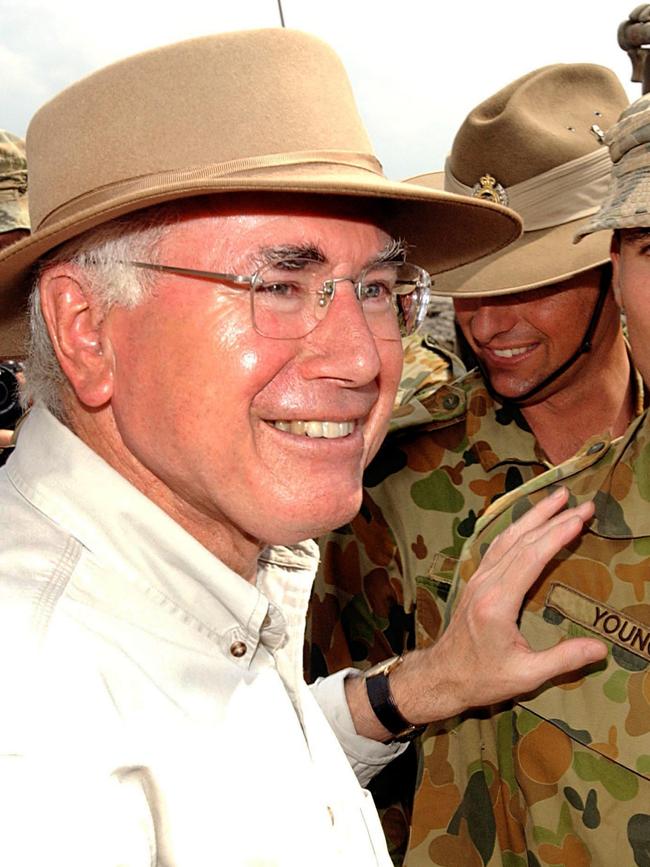

Alexander Downer was foreign minister from 1996 to 2007 and high commissioner to the UK from 2014 to 2018. He is chairman of British think tank Policy Exchange.

Way back in 2005 I accepted on behalf of John Howard the statesman of the year award from an American foundation. It reflected the enormous admiration there was around the world for the various things Australia was doing at that time.