Australia’s China debate is changing — we can’t allow ‘stability’ to distract us from Xi’s anti-West goals

One route would prioritise and act on Kevin Rudd’s warning, issued rivetingly in his new book, that the global political stage is set for an unprecedented battle led by Xi Jinping’s Beijing for influence, for ideas and narratives, and fundamentally for power.

The other – currently taken by Canberra – seeks to shelter Australia’s stuttering economy, by maintaining “stability” in China relations as its prime goal, thus hopefully dissuading Beijing from rebooting its commercial coercion. The case for this latter route is reinforced by our fast-developing political-class anxiety about ethno-religious voting.

This fear is clear. Criticise Hamas too vocally, and seats with significant Muslim voters may be lost. Criticise China, its Communist Party or its theocratic helmsman Xi, and ditto with Chinese voters. Next in line: Criticise Narendra Modi, and lose “the Indian vote”.

Much deeper analysis of Australia’s highly diverse ethnic Chinese communities is needed, including checking how many permanent residents choose to take up citizenship and can thus actually vote. However, presumptions about ethnic voting are already solidifying. So as we approach next year’s election, our major parties are already starting to compete to appear most “pro-China”, or least anti-China. In Australia, stabilisation denotes calmness and a return to both regular commerce and routine diplomatic links. In the People’s Republic of China, however, weiwen – “stability maintenance” – carries with it an undertone of suppression.

Australians do need to continue dealing with Chinese people and with Chinese businesses. But that’s getting harder as the ruling Chinese Communist Party ratchets up its pressing game, in pursuit of a new world order, a Pax Sinica.

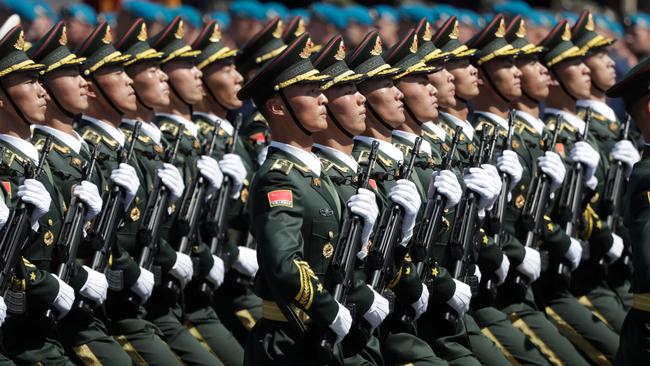

The People’s Republic of China, now 75 years old, is a more purposeful and organised ideological opponent of free democracies than was the Soviet Union. It is launching, Rudd says in his book, On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World, the “deepest assault on liberal economic theory that the world has seen”.

The resulting concerns are rightly being heightened on the eve of a pivotal US election, with Rudd adding that the context includes a decline in the appeal of universal human rights, and “democracy in retreat”.

Vladimir Putin underlined on Tuesday how Russia and its “no-limits” partner China view stability: “Russian-Chinese co-operation in global affairs is one of the main stabilising factors on the world stage.”

China’s ability to showcase to its own people its unique influence over rulers in the Global South, its supremacy in nearby seas, and its discourse-power over democracies and their values, has become crucial for the party’s core domestic domination. Since its now discarded reform-and-opening era, China has used its fast-growing economy to leverage its international political clout. And even though its economy is now sliding along with its demography, it continues to manipulate that habit of commercial dependence to keep the after-party alive.

In Australia, markets desperately latch on to the slightest hint of “stimulus” in the hope that the Good Old Days of insatiable Chinese commodity markets will return. They won’t. In Xi’s New Era, Beijing has other priorities, other fish to fry. Trade Minister Don Farrell said in March: “We’re talking about more meetings, more discussions, more trade” with China, including the latter soaring by a third to $400bn. Opposition Leader Peter Dutton later went one better, saying he’d “love to see the trading relationship increase two-fold”.

Australia’s economic dependency on China is now back where it was before the coercion campaign, with lobsters heading back to the tables of its wealthy. But Chinese politics drove the bans and tariffs, and could impose them again at any time.

The principal gains of commercial coercion come after the driver ends it, not during the bans. As with domestic abuse, the aim is to normalise the victim into a form of anxiety-led and instinctive deference, or in worse cases, quiet subjugation. Discourse-power is crucial for “Xi’s Marxist Nationalism”, as Rudd rightly points out. Foreign Minister Penny Wong – whose work in our region, including with China, has largely been commendable – told Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi last month: “We both understand the points on which we disagree won’t simply disappear if we leave them in silence.”

Quite right. But it is the public silence that Beijing especially covets – it can comfortably handle, by shrugging off, privately expressed concerns about human rights or the grabbing of islands. Chinese leaders are able to frame their visits to Australia to tell the desired discourse-power narrative back home.

When Wang Yi came in March, he paid a telling call on the Australian government’s loudest foreign policy critic, Paul Keating, who handily provided the desired message for the Chinese audience that “China’s development and revitalisation are unstoppable”, and its economy and development potential “do not pose a threat to other countries, and are conducive to regional peace and stability”, That word again.

And in the face of persistent attacks from a small but prominent circle of anti-American critics, we now hear little public championing in Australia of AUKUS, a key deterrent – along with intensifying our relations with Japan, South Korea, The Philippines and other regional democracies – against Xi’s pressing ambitions.

Stabilising relations with the PRC – following a narrative largely laid down by Beijing – has served us well enough for a few years.

But as Rudd writes: “Something new is happening with Xi’s China.” Must our worries about Chinese-Australian voters, or our lobster sales, turn “stability” into a straitjacket that prevents us responding adequately to this new challenge?

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

Behind the scenes, a vital debate is under way in Australian policy circles about how to handle China.