But in the highly unlikely event that the US President was still open to letting Australia off the hook, former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s ill-considered public comments on Trump – comparing him unfavourably with Chinese leader Xi Jinping – would’ve done Australia’s cause no good.

Either way, if Trump ends up pulling the trigger on his threatened tariffs, perhaps he will have done us a favour. It should be received as a much-needed wake up call for the Prime Minister and Peter Dutton, who both appear reluctant to acknowledge that, for better or worse, Trump is up-ending the world as we know it. Our Canadian cousins have been left in no doubt about it, but we – or at least our political leaders – remain in denial.

A lot of attention is focusing on Trump’s remaking of the global security landscape, but the potential implications of his tariff plans for the international economic order have not yet been fully acknowledged. At the heart of this order is the US-China economic relationship. While Washington and Beijing are strategic competitors, in recent decades their economies have become highly integrated.

Indeed, it’s no exaggeration to say that China’s late 20th-century industrial revolution would not have been possible without access to America’s huge consumer (for Chinese exports) and financial markets (for excess Chinese savings). Under Beijing’s development model, local economic growth was fuelled by exports rather than domestic demand.

The persistently high volume of local savings this resulted in (which could not be absorbed by local investment) has needed an outlet elsewhere, with US bonds and other financial assets proving particularly attractive.

Far from harming the US, China’s economic rise has enormously benefited it.

America’s transformation into a modern, technologically sophisticated economy over the decades leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis would not have worked without access to cheap manufactured exports from China.

The latter caused job losses for many in rust-belt states, but US incomes rose overall as capital, labour and land were shifted from low-value to higher-value activities. Moreover, without access to Chinese capital, Washington would not have been able to get away with perennial budget deficits; Chinese and other countries’ appetite for US government bonds have kept US interest rates lower than they otherwise would’ve been, giving Washington a licence to spend more than it otherwise could.

To put it bluntly, if the US has been the consumer of last resort for Chinese goods, China has been the financier of last resort for US spending. China exported almost $US440bn of goods to the US in 2024; and China holds $US1 trillion ($1.6 trillion) of US treasuries, second only to Japan.

The relationship of mutual economic dependence between the US and China has been a boon for Australia and other countries in our region. It has helped to preserve regional security. And it has enabled us to profit from our economic reforms of the 1980s and 90s.

In the more open, flexible and market-oriented economy this created, our entrepreneurs took advantage of China’s booming demand for natural resources (really, the demand of the joint Chinese-US economic engine) and our consumers benefited from the cheap goods it provided in return, raising their living standards.

Doubtless there were losers but, with productivity rising at a rapid rate in these decades, sustained economic growth – and the rising revenues it produced – enabled them to be looked after.

The biggest economic risk we face in today’s world is a breakdown of the US-China relationship. As we know, Trump has threatened to impose 60 per cent tariffs on China and so far has raised them by 20 per cent.

Is this merely a negotiating ploy, intended to force Beijing to further open the Chinese market to US exporters and investors? Or does Trump want his tariffs to be in place permanently, risking a disruptive – and for Australia potentially disastrous – economic decoupling of these two powers?

Until recently, I was confident Trump was more of a deal-maker than a dyed-in-the-wool protectionist. After all, in 2019, he negotiated a market access deal with Beijing after threatening tariffs against that country.

He must know that permanent tariffs – on China and other trading partners – will impose a deep negative supply shock on the US economy, slowing growth, raising prices and risking steep falls in US equity and bond markets.

Now I’m not so sure. As China and other countries retaliate, a possible trade war cannot be discounted. For policymakers in Australia, the imperative must be to prepare for the worst.

In a highly uncertain and increasingly dangerous world, all existing policy commitments must be reviewed. There can be no sacred cows.

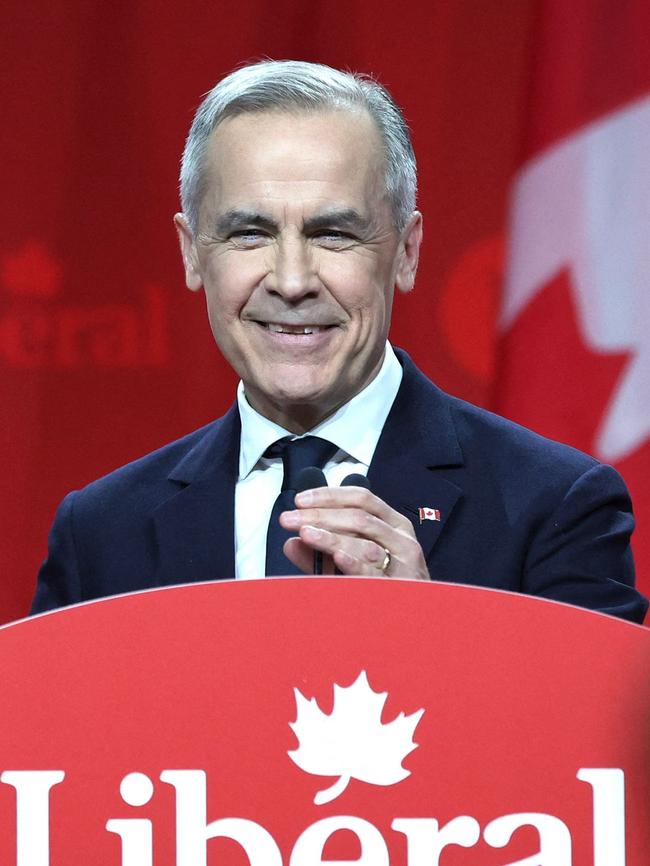

If Canada’s incoming prime minister, Mark Carney – a long-time climate change advocate – can immediately announce the scrapping of that country’s carbon tax on consumers, surely Albanese and the Opposition Leader can acknowledge things must change in this country.

Two priorities stand out. Not only should our bipartisan commitment to net-zero emissions be scrapped – noting the virtual collapse of the Paris Agreement – but Canberra’s addiction to entitlement spending and budget deficits also must end.

The latter can fund income tax relief, thereby transferring resources from the public to the private sector and raising the economy’s speed limit.

Some might prefer more money going to defence, but that should be considered only once we have an Elon Musk-like efficiency drive in this waste-ridden part of government.

We already know what Albanese and Jim Chalmers will do in this month’s budget. It will be more free gifts for all – to be paid for by the taxpayer – regardless of the gathering global storm clouds we face.

That will leave the ball in Dutton’s court.

Opposition leaders’ budget replies are usually ignored, but this one may be the most consequential we have had.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

Donald Trump’s announced tariffs on Australian exports of steel and aluminium to the US are likely to come into effect on Thursday AEDT. I suspect he decided against granting Australia an exemption some time ago, which would explain why Anthony Albanese never saw fit to travel to Washington to lobby for one personally.