Beijing has struck back at Scott Morrison. This follows its humiliation at the Prime Minister’s hands over the past two years in rebuffing China’s economic coercion of Australia, with Morrison being a catalyst in mobilising strategic resistance on a wide front against China’s aggressive tactics.

But Morrison is now exposed at Australia’s point of maximum vulnerability: our failure to secure the immediate region where Australia is the metropolitan power given our inability to persuade Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare from his China adventurism.

This problem has been misunderstood. It is not that Morrison was complacent. On the contrary, he tried and failed – and that’s more serious for Australia. It demands a national rethink to avert any domino effect in China’s favour. Any notion this setback could have been averted by a phone call, a belated visit by the Foreign Minister or more aid is a fantasy that doesn’t comprehend the challenge.

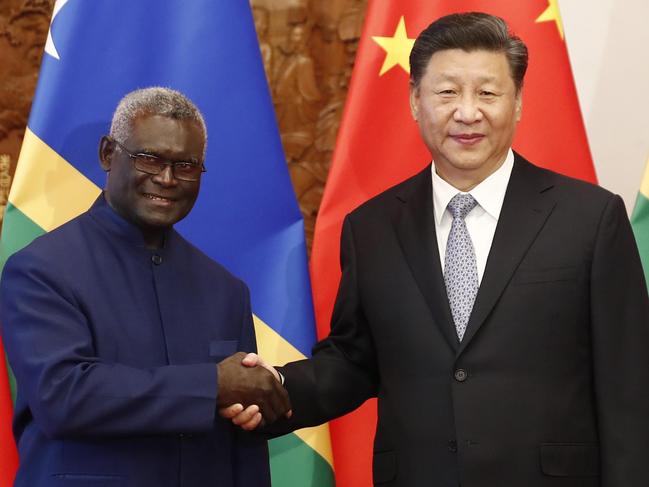

Sogavare’s secret agreement with China – the culmination of years of Beijing’s seduction – means Australia confronts a strategic competitor unrivalled in its history, with a great power that dwarfs our economy, our pockets and our military capability, uses tactics from bribery to coercion, and sells the idea that its destiny as regional hegemon is unstoppable.

What happens next is crucial. China, presumably, will move fast. The test is whether Sogavare’s deal will be seen as a self-interested blunder by a deceiving leader that is rejected by his own people and gradually unwound or whether it gets traction in the region and signals a growing acceptance of Beijing’s security penetration by other Pacific nations.

Australia cannot allow that to occur. It would turn a serious setback into a strategic catastrophe. It is not inevitable that Beijing will secure a military base from this agreement. But that decision must come from within Solomon Islands itself.

Australia cannot dictate these terms – but it needs to step up, offer more financial and defence assistance, target domestic opinion and get tougher about the consequences of entrapment by China.

Morrison has got what he wanted in this election – elevation of national security as a defining test – but not on the terms he expected. Labor, ironically, has turned this security agreement into a frontline election issue claiming it is the worse regional failure since World War II.

While Morrison has struggled in his reply, he has made three crucial statements. First, that Australia is working to secure a collective view in the Pacific of Sogavare’s decision – a view shared by Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Vanuatu, among others. This is essential.

Sogavare must feel the resistance from within his own region. “Our partners trust us,” Morrison said. “But we can’t kid ourselves. There is enormous pressure and influence which is placed on Pacific Island leaders across the region which the Chinese government has been engaged in for some time.”

Second, Morrison said Sogavare had promised him there would be no Chinese naval base – a promise that might be worthless given Sogavare’s behaviour. More important, the White House says Sogavare gave “specific assurances” to the visiting US delegation there would be “no military base, no long-term presence and no power projection capability” flowing from the agreement. The pressure from the US will be intense.

This was a significant US delegation led by Indo-Pacific affairs co-ordinator Kurt Campbell, with Honiara the final leg of a Pacific visit that included Fiji, a US-Fiji strategic dialogue and Papua New Guinea, where the US pledged to deepen its security ties.

While Solomon Islands told the US the agreement “had solely domestic application”, neither the US nor Australia believes this given the earlier leaked draft. The US warned there were “potential regional security implications” for the US, its allies and partners.

Campbell said if Solomon Islands breached these assurances from Sogavare the US would “respond according”. This falls in the zone between warning and threat.

Sogavare has plunged his tiny country into the cauldron of great power rivalry, yet this country has no pro-China ideological framing to buttress the stance its leader has taken. To a large extent this is about benefits for elites. The US starts a long way behind and China will be ruthless. But the pro-Christian, rugby-loving Pacific is not necessarily a comfortable fit with Beijing.

Morrison’s third statement, a sharp departure from the restraint he had been showing, invoked a “red line” saying that Australia “won’t be having Chinese military naval bases in our region on our doorstep”. On Tuesday he added that this red line “is US policy as well”.

These comments won’t help. They reveal the depth of Morrison’s frustration, how Labor has baited him, and his desperation to prevail on this security issue. Talk of a “red line” is great power language and designed to threaten. It is counter-productive for Australia in the Pacific. It will be used against Morrison and Australia. It is the product of an overheated election climate. It is contrary to Morrison’s cultivation of the Pacific family.

Worst of all, it invites the focus on Australia’s defence policy weakness: too much bragging and too little near-term capability. The terrible risk is that China actually presses ahead with a military facility to expose Australia’s weakness before the entire region.

Morrison tried to court Sogavare – Solomon Islands was the first country he visited after the 2019 election. The Turnbull government had earlier sponsored an Australian government-funded cable network after Solomon Islands threatened to team up with Huawei. Late last year Morrison worked with Fiji and PNG putting a police presence into the country to restore order and assist Sogavare.

The Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map shows between 2009 and 2019 Australia remained the major provider of overseas aid to Solomon Islanders, contributing 65 per cent of the total. Spending to the Pacific increased 24 per cent over this period but fell in relation to Solomon Islands given the phase-out of the regional intervention mission in that country. The current 2022-23 budget sees a record $1.85bn in assistance for the Pacific, representing a significant pro-Pacific weighting in terms of priorities.

Sogavare has long displayed hostility towards Australia; witness his distaste for the successful Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands project under the Howard government. Nobody yet knows the full extent of the political and personal gains he expects from his security agreement with China.

Whoever wins this election, a policy rethink and greater effort will be needed to reverse China’s gain. That will be an immense national challenge. Is Australia actually up for the task given a campaign that seems to be insular and unambitious and unprepared for any tough decisions about national security that might rattle our comfort zone?

“Who lost Solomon Islands?” is the wrong question for Australia today. Yet the recriminations in an election are inevitable given the betrayal of Australia’s Pacific family policy and the proof that China can threaten our country on its doorstep.