Although it was not hard for a 15-year-old girl to be lofted into the air, the real challenge lay in braving the moshpit below. It was a churning sea of people that could easily leave one bruised and battered. But emerging from this chaos was always a badge of honour – the physical gauntlet had been conquered.

That secular rite of passage, however, only exists in distant memory. In the early 2000s, there were no phones and no selfies. We were a generation who lived viscerally in the moment, not for virtual approval. I share this story because this activity – crowd-surfing – no longer exists, as far as I can tell. It is not permitted at most concerts today for safety reasons. Not only that, but the large music festivals of my youth are also going extinct.

The Big Day Out was cancelled in 2014, and this year’s Splendour in the Grass has been dumped, partially due to poor ticket sales. A lack of interest from Generation Z means the tribal gatherings of my youth are becoming far less frequent.

And although I am not yet 40, I am starting to look back on my own adolescence with a sense of wistfulness.I understand the thrills I experienced probably won’t be available to my own kids.

Wholesale changes to childhood and adolescence extend far beyond crowd-surfing at music festivals, however.

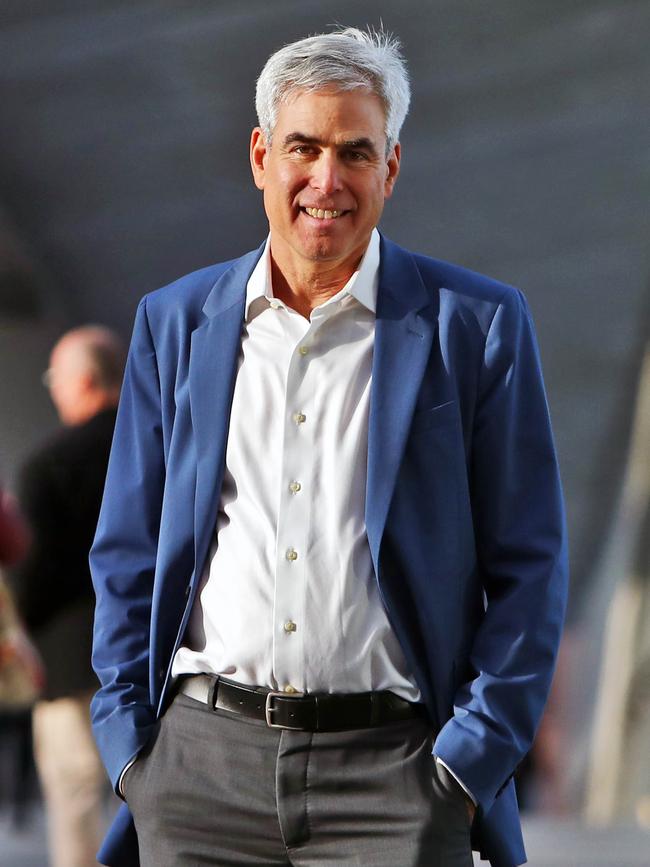

Jonathan Haidt’s fourth book, The Anxious Generation, has changed the conversation about phones, social media and young people in a way that may prove permanent. And it only hit the shelves a few weeks ago.

His book shows that young girls in particular have been hit by a tidal wave of mental illness since 2010, across the Anglosphere countries including Australia.

He argues that there is no other plausible explanation for this tidal wave of depression and anxiety than the ubiquitous uptake of the smartphone. Today, the average teenager spends more than seven hours, or 43 per cent of their waking hours, on their devices. And when they are not on their devices, they are worried about what’s going on online. Their agitated minds are elsewhere.

As an elder millennial (born between 1981 and 1995), I experienced a childhood free from phones and social media. We had a computer but it didn’t do much, and the internet was painfully slow. By the time I had my first smartphone I already had a degree.

Every one of us who came of age before the advent of phones and social media underwent formative brain development unmarred by attention-hijacking technologies. This is important.

It’s one thing for adults to become addicted to a substance or product, and another thing for children to become addicted before their adult brains have had a chance to form.

Yet Haidt’s book addresses more than just phones. It also explores the culture of “safetyism” and its impact on child development. Since the 1980s, parents, teachers, and other adults have increasingly attempted to insulate youth from risk, depriving kids of essential experiences for proper maturation. Let me explain.

Imagine a young child’s development like that of a tree. As a tree grows, strong winds buffet its trunk and branches. This causes the tree to produce what is called “stress wood” at its base. Stress wood fortifies the tree’s core, allowing it to remain upright and sturdy as it reaches greater heights. The more intense the winds, the more stress wood develops, resulting in a stronger, more resilient tree. Trees with stronger bases live longer and grow taller.

When we protect our children from wind – that is, when we protect them from the real world – we prevent them from developing their own stress wood. In our context, we don’t literally grow extra layers of bark, but we develop an internal confidence that we can look after ourselves, solve our own problems, and go through the world as agents of our own destiny.

That doesn’t mean children need to be thrown into situations that resemble the Hunger Games or be sent down into the coalmines of yesteryear. However, just as athletes must find the right balance between too little training and overtraining, there exists an ideal middle ground when it comes to childhood stress levels.

For the post-1995 generation, we seem to have created a toxic blend of too much stress in the virtual world, and too little stress in the real world in the form of physical and psychological risk-taking. And the result is a generation suffering anxiety and depression at record levels.

The solution is not just to take away the phones – although that would be a good start. It’s to reintroduce risky play as an important part of early life.

I believe my own lived experience – crowd-surfing, moshpits, and all – made me comfortable with taking productive risks as an adult. I married at 27, had my first child at 28, and started a successful business at 31. Would I have followed that agentic trajectory if, at the age of 15, I was addicted to consuming TikToks in my bedroom? It’s doubtful.

Claire Lehmann is founding editor of online magazine Quillette.

As a teenager, few experiences for me matched the thrill of crowd-surfing. In the year 2000, I attended my first big festival and remember floating above a sea of people in a ritual of hedonistic camaraderie.