Feeling out of whack, Darren Cahill was shocked to find he was suffering from depression

Darren Cahill is the GOAT of tennis coaches – but when there was little or no excitement about coaching or being at tennis, he found he was suffering from depression.

Darren Cahill felt out of whack. Wasn’t quite right. Might have been the Covid lockdowns. Might have been something more. He found a quack and asked the routine question. What’s up, doc? He was shocked by the diagnosis.

“The most surprising thing that came from my experience with depression was that I had no idea that I had it while I was struggling,” he says. “I knew things weren’t great and I felt off. Something wasn’t right but I believed it was related to a deficiency or illness somewhere in my body.

“I had multiple checks from doctors and blood work examined which showed nothing other than a couple of low markers but otherwise a very healthy 55-year-old male.

“From a mental health point of view, what did I have to complain about? I have a beautiful family and work in a sport that I love. I get to travel the world working with high-performance athletes and also work for one of the most powerful sporting networks in the world as a tennis analyst at grand slams for ESPN.

“My life was and is very good and I’m fortunate. Yes, there is pressure involved with my roles but I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Cahill is the GOAT of tennis coaches. Is he not? Patrick Mouratoglou has high-profile players under his wing and adores publicity, but Cahill just quietly and beautifully goes about his work. Not since Harry Hopman has a mentor guided so many world No.1s and major champions.

Jeez, times have changed. Hopman produced an army of successful Australian players in the 1950s and 1960s by treating them like army underlings. Strict discipline was the go. When Lew Hoad arrived at a match unshaved, Hopman told him, “The fine for that is 20 shillings.” When Hoad threw his racquet in the subsequent match, Hopman suggested from courtside, “That’ll be another 20 shillings.”

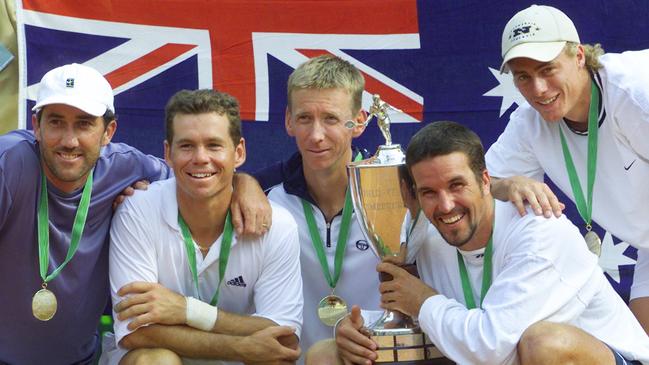

Cahill’s success with Lleyton Hewitt, Andre Agassi, Simona Halep and Jannik Sinner has led John McEnroe to call for Cahill to be inducted to the International Tennis Federation’s Hall of Fame. Hear, hear.

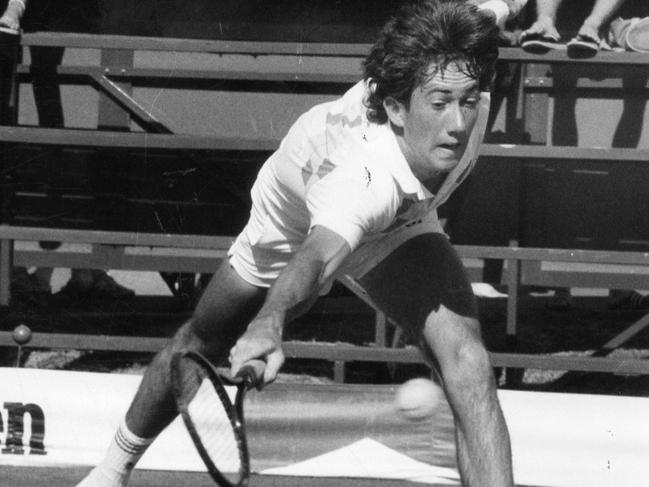

We forget he was a Wimbledon semi-finalist as a player. A world No.22. Just a terrific player who’s taken his extreme tennis IQ into a peerless coaching career.

Sinner spoke until he was Rod Laver Arena-blue in the face about Cahill’s care for him as a human first, tennis player second. Which stems from Cahill understanding, from experience, how easily someone, anyone, all of us, can just feel a bit out of whack.

In an interview with Inspiretek, the Las Vegas-based Cahill says: “As they say, coaching is the next-best thing to competing, when in fact it’s actually better and more emotionally rewarding in many ways. In short, I had nothing to complain about and basically thought that I just needed to boot myself up the backside to get going again after a difficult year, and a long stint in quarantine that left me flat.

“For Australians involved in the tennis tour, we were definitely lucky that we were able to continue to work and earn an income but it came with its difficulties (in Covid times). Once you departed Australia, re-entry back into your home country became extremely difficult with the tough border restrictions in place.”

He said: “When we left the country at the end of the 2021 Australian Open in February, most of us knew that we wouldn’t be returning to Australia until late September, at the earliest. My year was difficult professionally so it made the time away from family that much harder.

“After the US Open in September and a couple of cancelled flights by the airline, I made my way back to Sydney where I completed a 14-day quarantine period in a hotel room. There was a new restriction in place by the South Australian Government that earmarked Sydney as a ‘hot spot’, resulting in another 14-day quarantine period when entering South Australia. So, 28 days sitting alone in a hotel room contemplating where things went wrong in 2021, what I could’ve done better, how can I improve as a coach, and basically beating myself up about a difficult season that should’ve been better and taking responsibility for it.”

He revealed: “I emerged in late October from those 28 days in quarantine excited to see my family but knew something was wrong. A lack of energy, a loss of appetite, my mind racing at lightning speeds when my head hit the pillow, and a little anxiety over what was next for me in the tennis world. I knew it was a long, exhausting year and just believed I was tired and needed to refresh.”

He said: “But even three months later at the 2022 Australian Open, there was little or no excitement about coaching or being at tennis. I had dropped close to 13kg in weight, still felt exhausted, and couldn’t keep going. My tolerance was low for any problem that arose which was all confusing to me as patience and calmness are normally my stronger traits. I met with some doctors, and it became clear to them that I was struggling with depression and anxiety.”

A big-hearted bloke trying to help others – he needed help himself.

“The doctors were wonderful,” he told Inspiretek. “They educated me about how depression works within the brain and how it is treated. I went on medication to help me through the process and within a few months it felt like the clouds had cleared in my head, energy returned, eating habits became normal and things had become a lot clearer about what was needed to get going for the future.

“The excitement about getting re-involved within the coaching world of tennis had returned and two months later I was back on tour and loving every second of it. Maybe the biggest lesson I learned was that it can happen to anyone even if you believe you are in a good place in life. Ask for help if things don’t feel right and be honest with your communication. Don’t be afraid to express that you are struggling to those closest to you.

“I reckon tennis lends itself to mental health issues. You’re on your own on a court. Social media will tell you after a loss that you’re a choker, fat, ugly, boring or under-achieving. “Tennis is a little unique in that it is a one-on-one sport. We are alone on the court and the internal dialogue that we have with ourselves is not always pleasant. Learning techniques and building the framework to remain positive and see the good in what we accomplish play a massive part in being successful. The difference between what we do in life, in our work, or on the sporting field is very little and it all plays a big part in being the best possible version of ourselves every day.”

Cahill cares. That’s half his formula for success. He coached Hewitt from when the Bart Simpson of tennis was 12. Took him to world No.1 plus US Open and Wimbledon glory. He coached Andre Agassi from 2002 to 2006, when Agassi won the Australian Open and returned to world No.1. He coached Simona Halep to French Open and Wimbledon victories and the world No.1 slot. Sinner’s only just getting started. Cahill has climbed the peaks with players of different nations, personalities, genders and styles. The GOAT of coaches. Lockdown’s over.

“In the sporting world, most athletes are encouraged to build social media platforms with huge followings,” Cahill says. “It allows sponsors to leverage off the back of those following and creates more income potential for the athlete. It also leads to abuse, and taken the wrong way, can be damaging to an athlete’s mental health.”

Which means coaching has changed.

“Today’s young athlete is vastly different from athletes of past generations,” Cahill says. “They can’t be spoken to in the same way as an older athlete, and coaching has had to be refined and adjusted to move with the shift.

“There’s a sensitivity and judgment with every harsh word by any coach or teacher, whereas previous generations were seasoned to cop an honest ‘spray’ or ‘bake’ for a lack of performance as a way to get the best out of that athlete, to inspire and motivate them to improve.

“You need to think very carefully and know your athlete very well if you’re thinking of going down that path with the young generation. The new style of coaching is to show empathy, ask questions, challenge your athlete to come up with answers and provide a safe, stable environment where they can prosper.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout