In the lead-up to the 2022 election, Albanese said Labor would be about “renewal not revolution.”

The pitch was aimed at reassuring voters Labor would be a safe pair of hands following the high taxing, big spending agenda promoted by Bill Shorten going into the 2019 election.

Now, 14 months after winning office, the depth and scale of Labor’s renewal project is more substantive than what was initially apparent.

It ranges from the realignment of key economic institutions, changing the constitution to enshrine a permanent Indigenous voice to parliament, the creation of a new corruption watchdog in Canberra and a major reshaping of the industrial relations landscape.

Given the Coalition holds only 56 out of 151 seats in the lower house, Albanese knows he has a historic opportunity to make changes which serve Labor’s long-term political mission and which can endure beyond the current political cycle.

The proposed reforms to the Reserve Bank and the Productivity Commission will reshape both institutions to better suit key Labor values, while also addressing criticism from the party’s industrial wing towards both bodies.

The latest endeavour is the shake-up of the Productivity Commission, with Jim Chalmers appointing his former boss in Wayne Swan’s office – Chris Barrett – to take over the economic advisory body and modernise the institution.

While Barrett is well qualified for the job, his appointment signals to the unions that Labor has one of its own people running the body and that the government will seek to transform the Productivity Commission’s approach towards workers, the labour market and the role of clean energy as a future driver of growth

Labor’s shake-up of the Reserve Bank is also partly aimed at elevating the interests of workers, with full employment lifted alongside price stability as equal considerations in the setting of monetary policy. Responsibility for interest rates would also be handed to a new nine member monetary policy board, tempering the authority of the RBA governor.

Both examples speak to a sense of political maturity from Labor, but present risks to the framework which has underpinned modern Australian prosperity. But the contrast with the previous nine years of Coalition government is stark.

After a year in office, the Abbott government was in crisis, reeling from the unpopular 2014 budget which misread the national mood and the reintroduction of knights and dames. While he scrapped the carbon and mining taxes, Abbott’s change agenda was not rooted in seeking institutional change.

In 2016, Malcolm Turnbull went to a double dissolution election to re-establish the ABCC. Labor first scrapped the watchdog in 2012. Aimed at cracking down on lawlessness on worksites, the ABCC was well supported by the business community, but Labor did not give up the fight to remove it.

Albanese successfully abolished the ABCC for a second time in February. While the Coalition argued the body would boost construction productivity, it was Labor that won the argument. And Albanese is now using the instruments of government more effectively than the Coalition did to reshape the productivity debate.

The Coalition should take notice and think more carefully about how it could make better use of national institutions and how hard it is willing to fight for them.

More Coverage

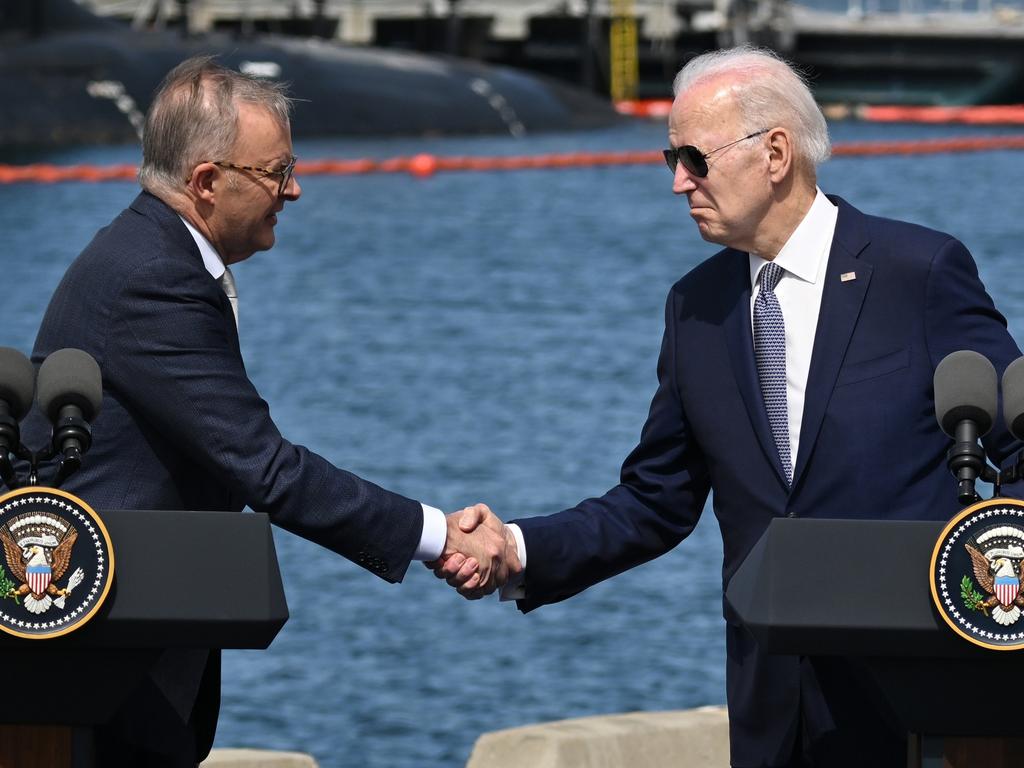

Anthony Albanese has emerged as a key change agent, pursuing a sweeping agenda that aims to leave Labor’s mark on the country in a way that conservative governments have failed to do.