The most extraordinary admission was that he still was not sure he really wanted to be prime minister. Peacock led the Coalition to the 1984 and 1990 elections and was defeated by Bob Hawke’s Labor Party. He was a spirited opponent and surprised many by how well he campaigned.

“I didn’t have this obsession with being prime minister,” he told me. “I wanted to do a good job in politics, but being prime minister was not the be-all and end-all for me like it was for others. I might have been better off if I had that same attitude, but that wasn’t me and no amount of rewriting can change that.”

Equally unexpected was his denial of any moral claim to a victory of sorts in the 1990 election when he led the Coalition to within a whisker of government, winning a 50.1 per cent majority of the two-party vote but a minority of seats. He said it was a clear victory for Hawke and Labor.

“I thought we would win,” he acknowledged. “But it was not to be. You have to win the seats — that’s the system. I never complained about losing the election and I didn’t think I was robbed.”

Peacock steered clear of commenting on Australian politics after exiting parliament in 1994, but he did convey two concerns that gnawed at him while living his final years in Austin, Texas.

First, he thought the Liberal Party was not the “broad church” it once was. “It’s been a major contributor to putting a centre-right view in Australian politics and I think it has been a force for good,” Peacock said. “But I think it is more conservative than it was.”

Second, he worried about the lack of comity between parties. “The respect between people of different views – is missing,” Peacock said. “Arthur Calwell and Bob Menzies had a great regard for one another. They would attack one another in the parliament but they never lost respect for one another.”

The first attempt Peacock made to enter federal parliament was at age 22 in 1961 when he challenged Jim Cairns in the seat of Yarra. When Menzies retired in 1966, the Liberal grandee wanted Dick Hamer to succeed him. When Hamer declined, this opened up the opportunity for Peacock to seize Kooyong at age 27. His star rose fast.

Peacock served as minister for the army and external territories in the Gorton and McMahon governments and held the portfolios of environment, foreign affairs, industrial relations and industry and commerce in the Fraser government. The job he enjoyed most was a surprise: external territories.

He played a key role in Papua New Guinea’s transition to independence. “Creating a nation out of 500 different tribes, 700 different languages, trying to draw them together and setting up a representative government for this diverse country, was a huge challenge and I loved it,” he said.

He regretted denouncing Malcolm Fraser and challenging him for the Liberal leadership in 1982. Peacock said he wanted the party to move in a new direction, which he tried to do when he became leader after the 1983 election: “I wanted (the party) to have a platform which was somewhat more liberal in the classic sense.”

The Peacock-Howard feud, which was as much about personality as it was about policy, had a debilitating impact on the Coalition during the 1980s and helped keep the Hawke government in power. Fraser told me he would have stayed on as Liberal leader if he had known they could not work with each other.

In 1985, Peacock tried to remove John Howard as deputy leader. When this failed, he resigned as leader. Peacock told me this was a blunder but insisted Howard had been disloyal. “There would have been a day of reckoning,” he recalled. “The divisions were becoming more and more apparent.” Peacock returned to the Liberal leadership, toppling Howard, in 1989.

Through the 1970s and 80s, Peacock was characterised as stylish and debonair, a veritable playboy of Australian politics. The suntan, dyed hair and bon vivant personality underscored this. He was intelligent and hardworking but the vogueish image sapped his credibility. What’s more, it probably cost him becoming prime minister.

Liberal and Labor research found that voters lacked confidence in Peacock’s capacity to be prime minister.

“During his days as minister for foreign affairs there was a strong feeling that he would one day make a great leader,” Liberal research found. “Reality has not matched expectation.”

Howard’s prime ministership probably would not have been possible if Peacock had not left parliament. But Peacock mended his relations with Howard and judged him to be “a very good” prime minister. His appointment as ambassador to the US in 1997, where he had deep friendships with Democrats and Republicans, came as a surprise. “I was quite amazed,” he recalled.

He enjoyed being ambassador and revelled in Washington intrigue. Peacock recalled ringing Howard to tell him Bill Clinton had been caught “receiving oral sex” from intern Monica Lewinsky days before it became public. The news, he thought, required a phone call rather than a cable.

“What do you think will happen?” Howard asked. “He’s finished,” Peacock replied.

“Boy, was I wrong on that one,” he said, laughing.

Peacock always lived life to the fullest, had few regrets and did not hold a grudge. In his sunset years he was very generous, overly so, towards the five Liberal prime ministers he had served as an MP, minister and ambassador. It is fitting that the tributes to him have been so equally big hearted.

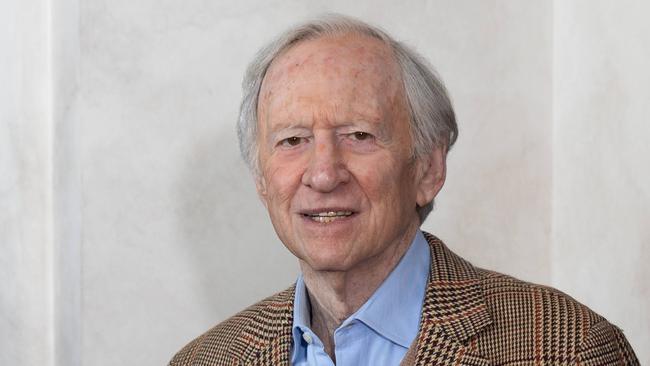

Andrew Peacock led a remarkable life, one bursting with potential, since he came to national prominence as the dashing heir to Robert Menzies’ seat of Kooyong in 1966. He was a minister in three governments, twice leader of the Liberal Party and ambassador to the US. I interviewed Peacock several times in recent years and was struck by the frankness in which he assessed his own life.