An Indigenous voice will help fight against endemic disease

It’s a chance to unify the country. As Health Minister, I can’t think of an area of policy where that voice will be more important and more valuable than in health.

With the best of intentions and substantial investment from both sides of the parliament, the current approach simply isn’t working.

Year after year, we hear the same reports of the yawning gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. There is an eight-year life expectancy gap between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians face disabling and often fatal rheumatic heart disease. This is a disease that was eradicated in developed countries more than 50 years ago but still strikes remote Aboriginal communities at higher rates than anywhere else on the planet, including sub-Saharan Africa.

Many, if not all, of the same risk factors for rheumatic heart disease also drive avoidable blindness. Ninety per cent of vision loss for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults is preventable or treatable. Trachoma, a contagious bacterial infection of the eye that causes inflamed granulation on the inner surface of the eyelids, is the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide.

In Australia, trachoma is found primarily in regional and remote First Nations populations. Australia has the dubious honour of being the only high-income country where trachoma is endemic. With one in 30 Indigenous children aged five to nine contracting trachoma, Australia is not on track to eliminate the condition as a public health issue in First Nations communities.

This is why the voice is so important. To fight endemic trachoma, we need to improve not only healthcare but also housing, basic amenities, and environmental conditions.

We need health, housing bodies and the environment department working together, listening to the voice of First Nations people to work towards preventing and eliminating trachoma.

I know we all care deeply about closing the gap, but we need a new approach. Just as a good doctor listens carefully to their patients, a voice to parliament involves listening to the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about better ways to make a real difference to their healthcare.

We know a voice will work for First Nations health because we’ve heard from health workers such as Georgia Corrie, a longstanding remote-area nurse in the Northern Territory.

She has seen the benefits of Indigenous-led healthcare but also the substandard outcomes of top-down approaches imposed on communities with little to no consultation. Corrie describes current healthcare policies as “walking between two different worlds” that do not talk to each other and do not listen to each other.

Importantly, as a First Nations healthcare worker, she sees the voice as an opportunity to bring those worlds closer together and, in doing so, to create solutions that actually work for Indigenous communities.

Listening to an Indigenous voice to parliament will give us a better insight into how better to spend the hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayer money that goes into First Nations health – getting better outcomes and better value for money. Politicians don’t know best – we need to listen to communities to hear their solutions and ensure funding is getting to where it needs to go, ultimately to ensure better outcomes and longer lives.

A voice to the parliament and, frankly, to the health minister, whether they’re Labor or Liberal, is a chance to turn a new page in our national efforts to close the gap. The voice to parliament is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the country to unite and break the cycle, making a real difference to the lives of Indigenous Australians.

Mark Butler is the federal Health and Aged Care Minister.

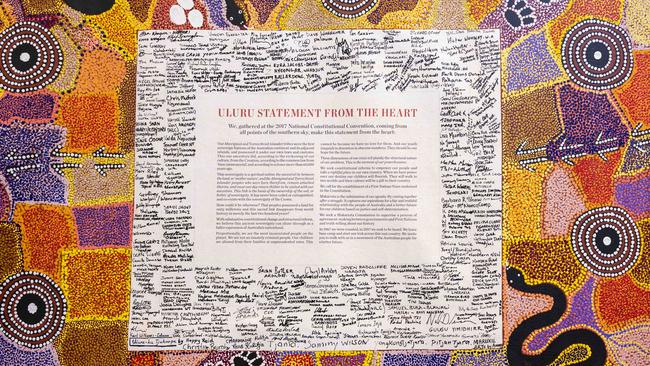

Later this year Australians will get the chance to vote to change our Constitution to recognise the place of First Nations Australians.