America will be on the inside looking out

Envisioning the post-crisis “new normal” is extraordinarily difficult. Yet it is not too soon to offer one safe prediction and to identify some yet-unanswerable questions about the shape of things to come.

The safe prediction is that the Indo-Pacific will remain the locus of global economic, political and military power — the 21 members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group deliver 60 per cent of the world’s economic output and close to half global trade. The economic predominance of the region is even more overwhelming if we add India.

APEC plus India likewise accounts for much — perhaps most — of the “knowledge production” in the world today. By such necessarily imprecise measures as publications in peer-reviewed science journals, APEC-plus-India authors are responsible for about three-fifths of global output.

The only state with truly global military capabilities (the US) is part of APEC, as are the only two other governments entertaining global strategic ambitions (China and Russia). Non-APEC members India, Pakistan and North Korea also have nuclear weapons. It’s almost impossible to imagine a configuration of states or regions that could displace the Indo-Pacific as the epicentre of world power.

As for the questions, the first concerns the scope and character of what we have been calling “globalisation”. World War I heralded the cataclysmic death of the first globalisation (1870-1914). Will the COVID-19 pandemic bring a brutal end to the second age of globalisation (1945-2019)?

At least for now, it seems as if a lot of things that have not yet gone wrong would have to, and at the same time, to sweep away the foundations for the networks of trade, finance, communications, technology, culture and more.

Yet it’s hard to see how we can carry on as if nothing much happened; much will need to change.

Until the advent of a biometric post-privacy future, free movement of peoples across national borders will be a nonstarter. “Davos” stands to become a quaint word like “Esperanto” as national interests and economic nationalism roar back. Global supply chains will tend to be replaced with domestic ones, notwithstanding the cost in production and to profits.

At the same time, today’s crisis may accelerate the demise of inefficient business models that had already outlived their usefulness: the “big box” store and retail malls, the unproductive but sociologically alluring business office, the law firm that charges for time rather than results, the higher-education cartel.

The creative destruction the crisis is unleashing will eventually offer immense opportunities, so long as resources from inefficient or bankrupt undertakings are reallocated to more promising purposes. The returns on remote communications will likely be high, creating incentives for impressive breakthroughs. Post-pandemic economies will need all the productivity surges they can squeeze out of technological and organisational innovation, for they will be saddled with a heavier burden of public debt.

Demographic trends and significantly less immigration, the shrinking of labour forces and the pronounced ageing of populations may characterise more economies, and not only affluent ones. Japan may become a model, but avoiding “Japanification” could become a preoccupation of policy makers, pundits and populaces in an epoch of diminished expectations for globalisation.

And how will the international community treat China’s increasing power? We have yet to conduct the authoritative scientific inquiry into the pandemic’s origins but there’s little doubt that heavy responsibility falls on the Chinese Communist Party and its collaborators in the World Health Organisation. Had the party placed its people’s health above its own, the global toll from COVID-19 would be a fraction of what it has been.

It would be bad enough if this crisis were a one-off. It isn’t and can’t be. The CCP does not share the same interests and norms as the international community that welcomed it. In the Xi Jinping era, China’s politics have manifestly been moving away from convergence as the regime has concentrated on perfecting a surveillance state policed by “market totalitarianism” — a social-credit system powered by big data and artificial intelligence.

The world will have no choice but to contend at last with a problem long in the making: the awful dilemma of global integration without solidarity. China is deeply interlinked in every APEC-plus-India economy and the rest of the world. Its interests are deeply embedded in many of the institutions that have evolved to facilitate international co-operation. How will the rest of the countries in the international community manage to protect their interests in such a world? Will it be possible to identify and isolate all the areas in which win-win transactions with Beijing are genuinely possible, and cordon off everything else? Or will the CCP’s authoritarian influence compromise, corrupt and degrade these institutions?

American voters are increasingly reluctant to shoulder responsibility for world leadership in the global order that Washington created and supported. Such discontent skews strongly with socio-economic status. For those in the bottom half of the income distribution, grievances with the status quo are based in experience. Over the past two generations, the American economic escalator has broken down for many. Since the arrival of COVID-19, the net worth for the bottom half of Americans has dropped further as their indebtedness has risen and the value of their assets (mainly homes) has declined.

In the US, the constitutional duty to secure the consent of the governed obtains for the little people, too, even if they comprise a majority of voters. In a post-pandemic world, it may be even more difficult to convince a working majority that the globalised economy and other international entanglements work in their favour.

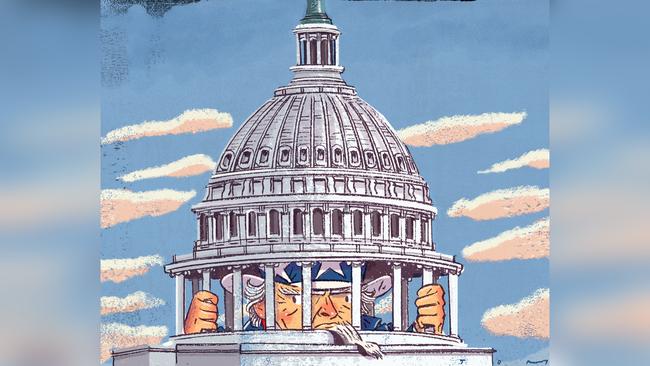

If US leaders wanted to generate broadbased domestic support for Pax Americana, they need to devise a workable formula for generating prosperity for all. Absent such a credible agenda, popular support for US international leadership could prove increasingly open to question. Declining domestic US support imperils the global order. If the Pax Americana is destroyed, its demise may be due not to threats from without but rather to pressures from within.

Nicholas Eberstadt holds a chair at the American Enterprise Institute and is a senior adviser to the National Bureau of Asian Research.

The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated the deepest, most fundamental crisis for Pax Americana since World War II. The coronavirus and its worldwide carnage came as a strategic surprise to political and intellectual leaders alike. Few had seriously considered the world economy might be shaken to its foundations by a communicable disease. Even after it happened, many were trapped in the mental co-ordinates of a world that no longer existed.