But his refusal to bow to Putin, fully aware that he was likely to die as a result, exemplifies hope and resilience. Author Mikhail Zygar wrote: “Now Alexei Navalny will be with us forever as an ideal role model.”

His bravery, in flying back to such a fate in Russia even after narrowly escaping death by Kremlin poisoners thanks to German doctors, is rare but thankfully not unique. It was a very modern martyrdom, one perpetrated by a totalitarian regime.

Such tyrannies seek pervasive control, not merely of what governments normally do but of all that happens within their borders – and, they would wish, beyond them. Rulers have only gained such capacities through technological and ideological “advances” in the last century or so.

Navalny’s murder is a sign that Putin’s Russia has graduated from authoritarianism to totalitarianism just as the excruciating death of Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo in China in July 2017 demonstrated for Xi Jinping’s People’s Republic of China.

A famous earlier martyr at the hands of totalitarian cruelty was German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who early identified the evil nature of the Nazi party and its idolatrous cult of the fuhrer or leader – a common feature of such regimes – and campaigned against its growing influence within the Lutheran Church.

He accepted an invitation to speak in the US just three months before Adolf Hitler launched World War II, but suddenly returned to Germany after a fortnight despite many pleas to stay. He explained to fellow theologian Reinhold Niebuhr: “I must live through this difficult period … along with the people of Germany. Christians in Germany will have to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that a future Christian civilisation may survive, or else willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying our civilisation and any true Christianity. I know which I must choose, but I cannot make that choice from a place of security.”

Bonhoeffer was inevitably arrested and eventually hanged shortly before the war ended, telling an English prisoner as he was led away: “This is the end – for me it is the beginning of life!”

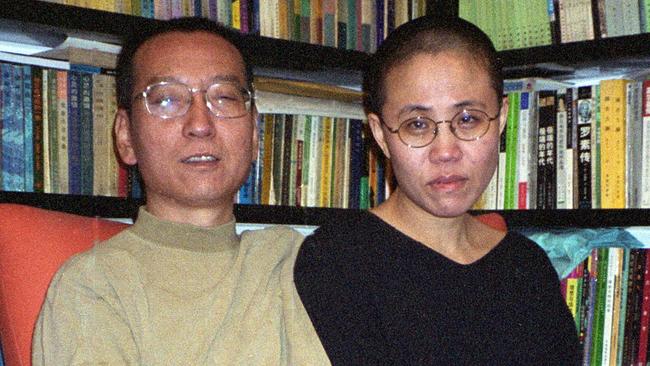

I may have been the last person to interview the then wryly fatalistic Liu Xiaobo, China’s pre-eminent contemporary philosopher. He was soon jailed for 11 years, on Christmas Day 2009, for “inciting the subversion of the state” by helping draft an online manifesto for a social democratic rather than a continuing Communist Party future for China.

He eventually succumbed to cancer while still incarcerated, receiving only cursory treatment and being denied access to foreign doctors his wife, Liu Xia, desperately sought. He had been jailed twice before, becoming, as the Nobel Committee described, “the foremost symbol of the wide-ranging struggle for human rights in China”. When I met him, he insisted he would not take up any of the many offers from eminent overseas universities. He had lived in Australia for five months in 1993, and remained fond of our country and his friends here.

But his life’s goal was a better future for China, which meant staying there, despite the natural anxiety causing him to glance around frequently as we talked in a Beijing tea house: “This is my country,” he said simply.

Liu told me political activity “traditionally takes place inside a dark box in China. Everything is a state secret, even a leader’s health”. He was soon enough himself placed inside such a dark place, where his own health was kept secret and effectively taken from him, with his freedom.Navalny posted on Facebook a month ago: “I don’t want to give up either my country or my beliefs. I cannot betray either the first or the second. If your beliefs are worth something, you must be willing to stand up for them. And if necessary, make some sacrifices …”

Such martyrdoms underscore the true fragility of totalitarian powers, whose credibility relies on total subjugation. If one brave soul refuses to submit, surely others might follow. Visitors to London’s Westminster Abbey should look up as they enter through the Great West Door, at statues honouring ten such 20th century martyrs, including Bonhoeffer, Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia and Pastor Wang Zhiming of China.

There are further leading figures who, still very much alive, have refused to abandon their countries and causes, even facing mighty odds. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky famously responded two years ago to a US offer to fly him away as Putin invaded: “The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride.”

Myanmar leader and Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has for decades suffered house arrest and now jail under the military junta. Earlier permitted to leave on condition she never returned, she refused, writing: “The only real prison is fear, and the only real freedom is freedom from fear.”

Sadly, the enemies of freedom can sometimes suck up rare succour from useful idiots. The recent Putin interview arranged by the Kremlin with Tucker Carlson was an example. On these pages, Paul Monk listed seven key issues Carlson should have raised, and even Putin mocked his invitee’s “lack of sharp questions”.

And how many public protests have we seen in Australia in support of martyrs for freedom such as Navalny or Liu?

German pastor Martin Niemoller warned in 1946, after surviving concentration camps, about complacency in the face of tyranny: “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out – because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists”, ditto. And the Jews, ditto. “Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Navalny isn’t resting in peace, his martyred soul is restlessly summoning resistance.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

The effective assassination of Alexei Navalny is both profoundly upsetting and uplifting. His death at the hands of corrupt dictator Vladimir Putin is of course deeply troubling at every human level.