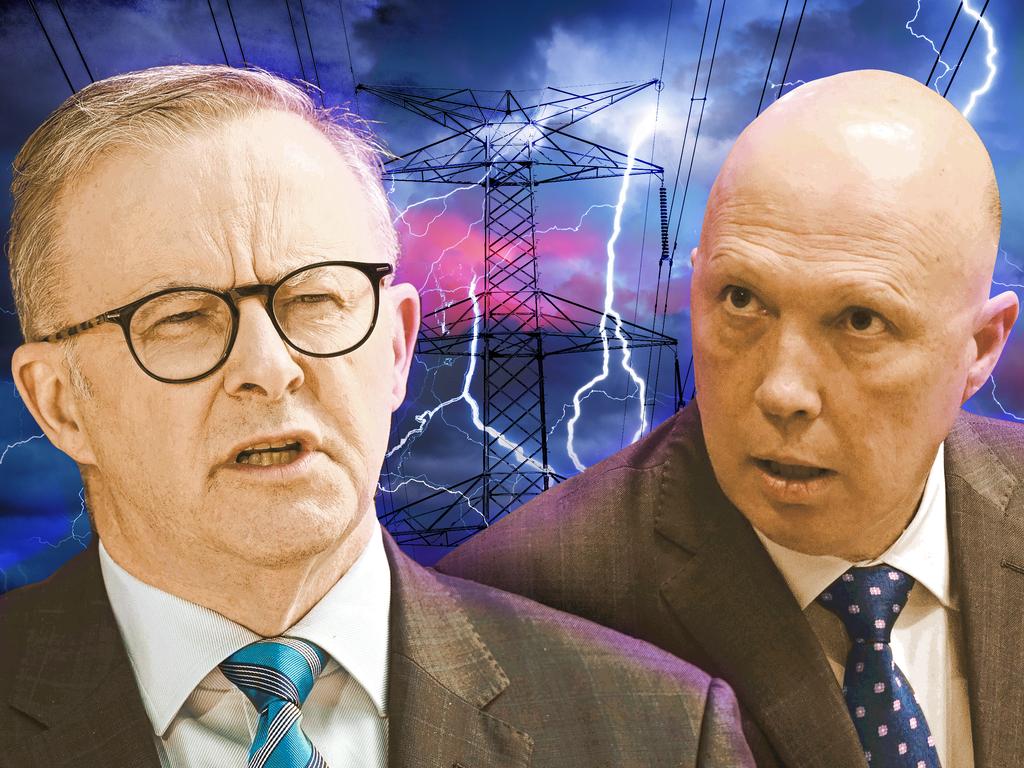

Albanese defying laws of economics at nation’s peril

Seven months into his prime ministership, it is increasingly apparent Anthony Albanese is unlike his predecessors. Monday’s Newspoll results signal this is not just a honeymoon. He is a different kind of Labor leader. His key policy initiatives may be radical, but his methods and governing disposition are distinctly conservative. The man who likes “fighting Tories” is behaving as one.

A key lesson offered in Graham Richardson’s book, Whatever It Takes, is the best way to understand power is to be deprived of it for an extended period. Albanese may have won his seat of Grayndler 10 times in a row, but on seven of those votes Labor lost the election.

Albanese is the most experienced individual to become Prime Minister. He is Australia’s 31st and none of the prior 30 had as extensive an apprenticeship before getting the top job. Harold Holt may have been in parliament longer before becoming PM, but he did not have the depth or range of Albanese’s experiences.

In addition to a front-row seat to the rise and fall of seven PMs and 10 opposition leaders in his 26 parliamentary years, Albanese has been a backbencher, a frontbencher, a minister, shadow minister, deputy PM, opposition leader, leader of the house and manager of opposition business. Albanese is a case study of Robert Conquest’s first law of politics: “Everyone is conservative about what they know best.”

This cautious governing disposition also extends to his cabinet, which counts 14 prior federal ministers, a former ACT chief minister and a former NSW deputy opposition leader. There are decades of experience within this team; they know the exhilaration of government but, critically, they know the despair of opposition and how quickly the former can become the latter.

The most striking gap in Albanese’s parliamentary resume is the lack of a senior economic portfolio. This is perhaps why he should consider the advice given to Bill Clinton in 1992: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Campaigning in March, Albanese said: “If Labor is successful in the coming federal election, I will take my lead from Bob Hawke and his successor, Paul Keating.” Not from Gough Whitlam, Kevin Rudd or Julia Gillard, but from the most economically conservative and successful Labor leaders in Australia’s history.

Upon his election, Hawke focused on the domestic economy believing his political future depended on how well it was managed. This led to significant economic and productivity-enhancing reforms that are still paying dividends today. Albanese, like Hawke, inherited a significant budget deficit, a bloated government, and an inflationary environment. The low-productivity economy in 1983, then as today, was due in large part to the regulatory leviathan pressing its foot on the nation’s economic throat. Unlike Hawke, Albanese does not seem interested in economic reform or productivity. On the contrary, his industrial relations and energy laws will inflict productivity damage and reverse several Hawke-Keating reforms.

Australia’s economic headwinds are blowing hard and cold with a rapidly deteriorating global environment. Economic reform is increasingly necessary to maintain prosperity and reverse the regulatory asphyxiation of Australia. And not just from headline policies such as energy and industrial relations, but also from bureaucratic business as usual.

Recently, the Australian Law Reform Commission wrote: “On a variety of complexity metrics … the (Australian) Corporations Act often stands in a class of its own.” One can but imagine the adjectives that could describe Australian tax and environmental laws. Also recently, Austrac chief executive Nicole Rose advocated to extend money-laundering laws to “gatekeeper professions” such as real estate agents and suburban accountants. Not because of evidence of systemic malfeasance but for fear of criticism from an international body. That many businesses already struggle to meet existing regulatory burdens seems inconsequential.

Extensive and complex regulation is a tax on productivity, constricting economic growth. It is a subsidy from small to large business because it is large businesses that can afford the lawyers, accountants, consultants and lobbyists necessary to navigate the regulatory labyrinth. Deregulation and economic reform are as imperative today as they were in 1983. Unfortunately, there are no signs the Albanese government has any interest in economic reform, just as there was no interest from recent Coalition governments. Instead, the Albanese government continues to pursue economic and structural de-form through increasing market interventions, taxation, government spending and regulation.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that bankruptcy comes “gradually and then suddenly”. Already, total government expenditure sits near 50 per cent of GDP. There is an unprecedented level of (non-war) government and semi-government debt. There are 2.2 million public sector employees costing near $200bn a year. And Australia’s energy market has become a centrally planned Frankenstein.

Decades of economic history has shown private property, rule of law, free and competitive markets, and limited government drive prosperity. These prescriptions are the exact opposite of many policies implemented in Australia over the past 20 years. There should be no wonder why the economy is stagnating.

PM, if you want to achieve a Hawke-Keating legacy and for yours to be a well-regarded long-term government, it should be remembered parliaments can vote to change many things but not the laws of economics.

Dimitri Burshtein is a former government policy analyst.