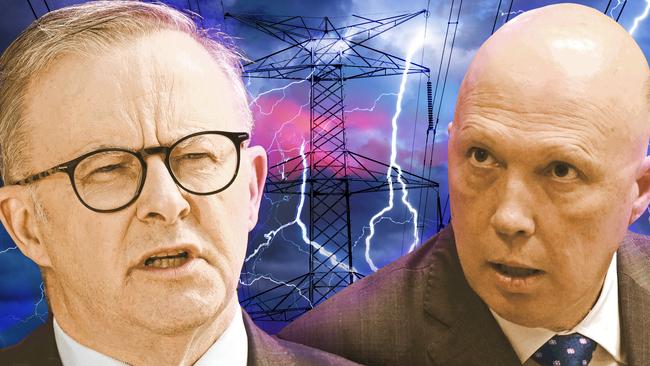

Power play could blow up in Anthony Albanese’s face

In the first significant political risk from Anthony Albanese since the election, Labor is on a collision course with the resource and energy giants, leaving the industry reeling and economists and energy experts baffled.

Anthony Albanese this week set the government on a collision course with the resource and energy giants, embarking on an unprecedented intervention in the market that has left the industry reeling and economists and energy experts baffled.

It is the first significant political risk from the Prime Minister since the election seven months ago.

Citing extraordinary times as a trigger for extraordinary measures, Albanese has gone to war with the energy sector.

He is backed by a broad consensus on the economic and social case for intervention over unjustifiably high domestic energy price rises.

With the government firing the first salvo, the industry has now fired back with a suspension of negotiations with buyers for new supply into the east coast gas market. In response, the Albanese government has dangled the threat of invoking the trigger powers set up by Malcolm Turnbull by forcing supply.

The imposition of price regulation by ministerial decree as a permanent fixture of government exposes Labor to accusations of political overreach from a leader elected on a promise of renewal rather than revolution.

“It is weird, I don’t quite understand it,” the Grattan Institute’s widely respected energy expert Tony Wood told Inquirer.

“I thought they were on the cusp of an extraordinarily clever political compromise and instead they seem to have created a war that was unnecessary.”

On the back of industrial relations laws that attracted unflattering comparisons to the 1970s, there is a growing sense in corporate Australia that traditional ideological motivations are creeping back into the new Labor government’s response to major economic questions.

Partnering with the Greens by striking a multibillion-dollar deal for consumer energy programs in exchange for their support in the Senate to pass its price cap bill on Thursday will serve only to reinforce the perception that there has been a shift in attitude inside the Albanese cabinet.

At the same time, Albanese has also set a new bar for political success that he probably didn’t need to. The energy package, including an as yet undefined rebate for welfare recipients, as well as the promise of broader bill relief for households and businesses, is unsurprisingly popular with consumers who have little interest in the complexities of the energy market.

In his speech to parliament before the introduction of the enabling legislation, Albanese sought to define the political contest for the year ahead. “You can vote for this plan to stand up for jobs, industries and households, or vote against it and stand with companies banking record profits and sending them offshore, that’s the choice,” he told the House of Representatives.

But Albanese will need to craft a more robust narrative going forward to manage people’s expectations of what the government can actually deliver. The pledge that by this time next year a moderation of skyrocketing gas and electricity prices should have kicked in due to the price caps on coal and energy is now etched in stone.

The Prime Minister has put a figure on the savings for consumers. At $230 per household, it is slightly less than the $275 cut to power bills by 2025 he pledged as part of his election energy plan. If he doesn’t live up to what has now been promised, the eventual electoral fallout could be acute.

The tactical positioning by Albanese in the lead-up to this outcome has mirrored the wedge politics of the IR debate. No state government or Senate crossbencher was going to stand in the way of money for households, despite their reservations.

Peter Dutton has decided to play a longer game in resisting the wedge, opposing the legislation, and banking on the belief that it will fail. The Opposition Leader believes the counter-narrative has already been written for him by Albanese: the Labor plan involves power bills rising by 23 per cent.

“They don’t realise it yet, they’re excited about their win, they’ve got the support of the Greens, and when the Labor Party and the Greens come together on economic policy you know trouble is on the horizon,” Dutton told parliament in his response to the bill.

“You know that power prices under this government will continue to go up and up. You know the uncertainty they’re creating in the marketplace will mean a reduction in investment.

“It’s shambolic. I honestly believe that this is catastrophic for economic policy in this country.”

Having delivered on most of Labor’s commitments in record time, Albanese has not only consolidated the government’s position since the election but has also strengthened his leadership credentials.

He has had the most successful starts for a newly elected government since Kevin Rudd ended 11 years of Coalition rule in November 2007. Labor’s primary vote is now six points ahead of its election result and Albanese’s personal approval ratings continue to reflect record high levels.

Electorally, there is no sign of buyers’ remorse with the re-election of a Labor government after almost a decade in the wilderness.

With these early successes, it begs the question as to why the Prime Minister has taken a gamble on his energy plan, when all evidence suggests he didn’t need to. The risk of overreach must now be calculated into the political equation.

While the sector would have probably accepted a temporary price cap, and moved on, the mandatory code of conduct with a permanent “reasonable price” mechanism has sent the energy and mining CEOs into meltdown.

“The proposed measures will not solve underlying issues around energy supply availability, and will potentially distort and discourage longer-term investment,” says Geraldine Slattery, BHP’s president for Australia. “The proposed ‘reasonable price provision’ also creates significant uncertainty for market participants well beyond the immediate inflationary period. The government should, at the very least, put in place a time limit or framework for what triggers would lead to regulations being eased.”

At the same time, Shell and Woodside, two of the three big gas suppliers, warned of a collapse in future investment in gas, leading to a supply crisis and higher prices. The argument is that Albanese’s plan to ameliorate price rises will only serve to push them up by more over the longer term.

“They should have sat down with industry to solve a longer-term problem,” says Wood. “They didn’t and instead just announced this mandatory code of conduct. And it’s blowing up in their face.”

Economist Chris Richardson is equally perplexed at the permanent feature of the package in relation to ongoing price control.

“There is definitely a problem and it makes sense to have a go,” Richardson told Inquirer.

“We have an inflation problem that is increasingly centred around gas and electricity prices,” says Richardson. The effect, he said, was a squeeze on the living standards of families while the interest rate reaction of the Reserve Bank was slowing the economy.

“Gas and electricity prices are one of the few things we have got as a potential lever in a cost of living crisis. There is a case for doing something.

“This problem was already evident when they won power. You couldn’t have been looking at the electricity futures and have anything other than a deep feeling of foreboding.”

But Richardson believes the $1.5bn package for welfare recipients – which becomes $3bn when state contributions are taken into account – could well end up being inflationary, despite Treasury’s claim that it will knock 0.5 per cent off the consumer price index. He questions the need for it at all.

“The politics of the extra $1.5bn is good … the economics of it is not good,” he says.

“The real problem is that we don’t tax gas well, we don’t regulate the east coast markets well. That is what you spend 12 months running around doing while the sticky tape is in place.

“Instead, they have a reasonable price thing as an ongoing one. I don’t get that. They could have done a bit less and achieved the same political outcome … and then spent the next 12 months fixing up taxation of gas and the regulation of the market.”

The Albanese government’s premise is that the east coast energy market is fundamentally broken and that the only way to fix it is for the government to get the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission to regulate prices.

“Now that is an extraordinary leap,” says Wood.

“And it’s an almost impossible job too.

“What they could have done is say ‘look, we are going to do the price cap, but we do also need to think about what the longer-term situation looks like, we don’t want to get into this situation again’. But they don’t need to do it this way. Instead of a skirmish, you now have nuclear war.

“It’s a mystery to me why they felt they needed to do it.”

Albanese was quick to identify the existential problem for Labor three years ago in the party’s post-election review of the 2019 defeat – chiefly that it had failed to find a way to speak to the party’s competing constituencies, the new left as expressed by inner city elites and the traditional blue-collar base and the battle over the future of coal.

Prior to the 2022 election, Albanese backed the expansion of fossil fuel projects, for fear of repeating 2019. But his offer of a new style of government, governing in consensus and consultation with business, is beginning to ring hollow with corporate Australia.

US oil giant ConocoPhillips this week declared that the Albanese government was now acting in a manner that was demonstrably “anti-business”, and by doing so it had added a component of risk to the investment environment in Australia.

These are charges that Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers reject, countering that the energy industry had been on notice for months that a mandatory code was coming.

In the same week as the government announced its price package, it secured agreement from the states on a capacity mechanism to ensure supply of dispatchable power and prevent shortages, which excluded coal and gas from the equation.

Combined with the price caps, this has added to the atmosphere of hostility, which can only be compounded by the new pact with the Greens, which the minor party is heralding as “the end of gas”.

The problem for the longer-term optics, beyond Labor’s left-wing constituency, is obvious under this arrangement.

“The government has a self-imposed problem for them to achieve, and to be fair the Coalition signed up to the same objectives, those (climate change) targets, (so) we have to stop burning gas the way we do anyway,” says Wood. “But in the short term we can’t, we need gas for our homes, we need gas for our businesses, we need to make chemicals, fertilisers, and all that stuff.

“The other side of the capacity mechanism is that it has been known for quite a while that we need some way to deliver dispatchable capacity,” he says.

“I don’t know any place in the world that has introduced a serious capacity mechanism system without fossil fuels in it.”

Wood agrees that Albanese had no choice but to act. Even the industry recognises this. And there is blame on both sides. A compromise should have been struck before it got to this.

“Putting that aside, they now have to stitch it together, and it will take quite a long time to work out how this is all going to work in practice,” Wood says.

“And then they are going to have to have a very good narrative to make sure they haven’t created expectations that will not be met,” he adds.

“Because if this all unwinds on them in the second half of next year, you are starting to get into campaigning for the next election.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout