The decision comes after revelations that yet more terrorists – including Fateh al-Sharif, the head of Hamas in Lebanon, and Hamas commander Mohammad Abu Itiwi, who was involved in the rape and murder of the young men and women attending the Nova music festival – were long-time UNRWA employees. But those revelations merely highlight a fact that has been obvious for some time: that UNRWA is part of the problem, not of the solution.

The severity of the issues became apparent in the organisation’s early years. Established in 1949, UNRWA was one of the agencies set up to help address the vast population movements, involving some 50 million people, that occurred in the wake of World War II.

An influential report by Sir John Simpson had concluded that repatriating large numbers of refugees was unrealistic and ought to be “ignored in any future program of international action aiming at practical liquidation of refugee problems”. Rather, international assistance should facilitate the refugees’ resettlement in host countries.

In only two instances were geographically specific entities created to deliver that assistance: Korea and Palestine. In both cases, the entities were intended to be strictly temporary. The UN Korean Reconstruction Agency’s mandate was terminated in 1958, when South Korea, which was still in ruins, assumed the burden of refugee resettlement. And UNRWA’s mandate was meant to be terminated by that time too.

Because “sustained relief operations inevitably contain the germ of human deterioration”, said UNRWA’s establishment report, “every effort should be made to transfer relief administration to (host) governments no later than 1 July 1952”. To that end, the agency was to concentrate on works programs that would promote the refugees’ integration into their new homelands.

However, those programs never got off the ground. As early as 1950 the Soviet-aligned Congress of Palestinian Refugees denounced the works program as “a project prepared by the Imperialists”, whose goal was to deprive Palestinians of their “right of return”. By late 1951, UNRWA’s 12,000 Palestinian employees were, the agency reported, on strike “against making any improvements in (refugee) camps in case this might mean permanent resettlement”.

The Palestinians’ objections were understandable. After all, wrote journalist David Hirst, they had been assured by their leaders that “all you have to do is eat and sleep – the Arab armies will get your country back for you”. In the meantime, declared the General Union of Palestinian Students, since “the people of Palestine have been wronged, it is the duty of humanity” – that is, of the West – to “provide them with tranquillity and ease”.

The result, UNRWA reluctantly recognised, was that “the relief given by the Agency is considered a right” that could not be made conditional on any form of work. The agency therefore abandoned its public works program in 1957, refocusing on delivering ongoing welfare payments, schooling and health services.

That suited the host countries, which, with the partial exception of Jordan, refused to accept the refugees as permanent settlers. Fearing they would cause turmoil, the host countries’ security services kept the refugees, and especially the burgeoning population of UNRWA schoolteachers, under tight control, curbing their nascent militancy.

Lebanon, to take but one example, was regarded as less repressive than Egypt was in Gaza; but in his memoirs, Ahmed Kotaish recalls that his school principal was “publicly whipped and deported for raising the Palestinian flag in front of the school”.

However, the situation changed dramatically in the 1970s. In 1969, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser brokered the Cairo Agreement between the Lebanese Army and the Palestine Liberation Organisation that placed the UNRWA-run camps under the authority of the PLO instead of the Lebanese state. As well as contributing to Lebanon’s eventual collapse, the agreement effectively put the PLO in charge of UNRWA’s provision of services, with UN General Assembly resolutions 3237 in 1974 and 31/110 in 1976 then giving the PLO unprecedented standing in UNRWA’s supervision.

At the same time, Israel, having occupied the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 war, was far more liberal than Egypt and Jordan had been, granting Palestinian organisations freedoms of expression and association they had never previously enjoyed.

All that opened the road to the unchecked infiltration of UNWRA by the PLO and its splinter groups, including, in later years, Hamas. Initially, UNRWA treated that as a grave concern, with Commissioner-General Laurence Michelmore and his successor John Rennie noting that it raised “basic questions of authority”.

However, Olof Rydbeck, the Commissioner-General from 1979 to 1985, viewed the agency’s symbiosis with the Palestinians as a way of inducing the Arab states to provide UNRWA with supplementary funding, ensuring its continued expansion. While UNRWA instructed its senior staff to “adopt terminology which will ‘discourage’ (the) total identification of UNRWA with refugee camps”, Rydbeck forged so close a partnership with the PLO that Yasser Arafat (who publicly denounced UNRWA as an imperialist tool) addressed him, in their personal correspondence, as “Dear Brother”.

Matters came to a head when Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 led to the discovery that UNRWA’s Vocational Training Centre in Siblin was a well-equipped military base. Israel and the US protested but Rydbeck, with the support of the Arab states and the Europeans, made purely cosmetic changes – and, in an ominous precedent, got away with it.

There have, since then, been countless commitments to reform, including, most recently, after a review chaired by former French foreign minister Catherine Colonna. The reality, however, is that under the current Commissioner-General and his predecessor, who resigned amid allegations of pervasive corruption and mismanagement, they have had no effect.

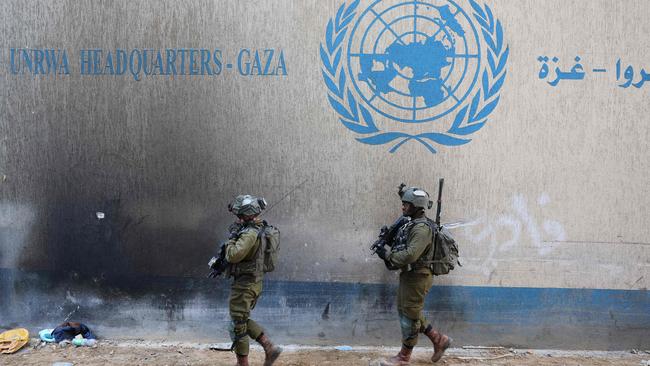

As the fact that dozens of UNRWA facilities in Gaza have been found to house military assets shows, UNRWA’s staff systematically ignore violations of its regulations. Nor is it possible, after the latest disclosures, to deny that UNRWA provides the salaries on which many terrorists rely.

But the damage is broader than that. By acting as a caretaker for generation after generation of so-called refugees, most of whose parents and grandparents were born in their current place of residence, UNRWA has converted refugee status into an inheritable entitlement well worth preserving. Having thus encouraged Palestinians to permanently depend on welfare, it has sown the very “germ of human deterioration” its establishment report decried.

Today, compared to the UN High Commission for Refugees, which copes with populations perpetually exposed to violence and starvation, UNRWA has 8.6 times as many employees per refugee served, reflecting its uniquely generous funding.

Much of that funding sustains the terrorism that has repeatedly plunged the region into devastating wars. If Western governments genuinely want to advance the cause of peace, it is high time they worked with Israel to devise a credible alternative.

Earlier this week, in a vote that united Benjamin Netanyahu’s staunchest supporters with many of his greatest critics, Israel’s parliament overwhelmingly approved legislation that would curtail the operations in Israel, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank of the UN Relief and Works Agency.