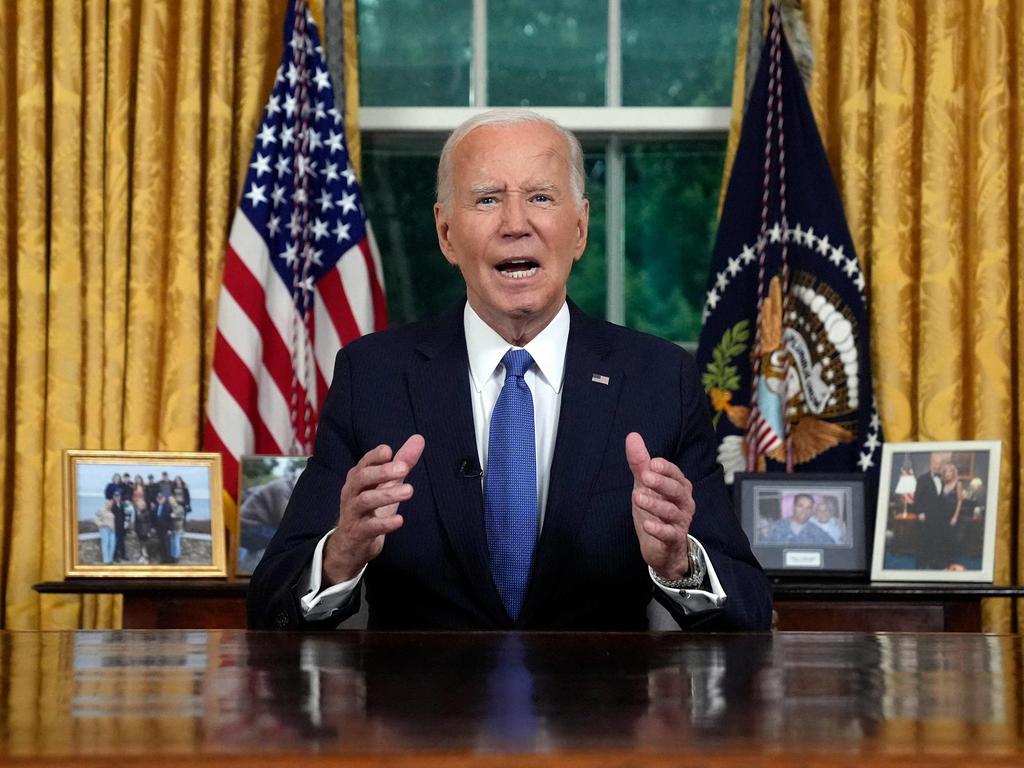

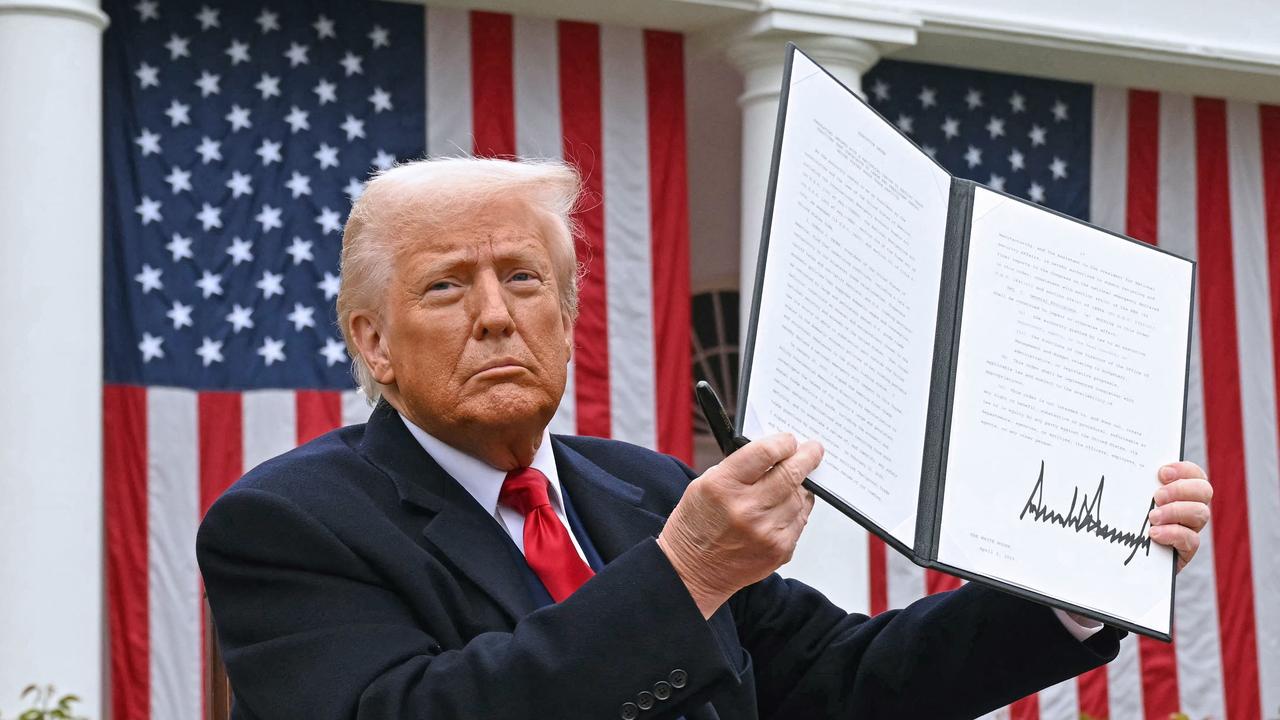

After a month of age-related polemics, Joe Biden might heartily agree – and now that age is likely to weigh against him, so might Donald Trump. But for all of the recent controversy, empirical evidence about the impact of age on presidential performance has been conspicuously lacking.

There are, for sure, complex issues involved in piecing that evidence together. Age, for example, seems straightforward. However, a 55-year-old in 1850 had only as many expected years of remaining life as a 70-year-old a century and a half later. As a result, when Trump was inaugurated, at 70, in 2017, his “age” measured in terms of expected life span was about the same as that of Rutherford Hayes, who became president in 1877, aged 54.

Measuring performance is even more fraught. American historians have a long tradition of ranking presidents from best to worst. Some of the errors that involves can be offset by averaging the various rankings. But while scholars are unlikely to have strong partisan feelings about Chester Arthur or Calvin Coolidge, biases are difficult to avoid when it comes to George W. Bush or Barack Obama – and even more so with respect to Trump.

Rankings of the most recent presidents must therefore be treated with caution. And so, given the myriad difficulties, must the findings of the analysis Joe Branigan and I have conducted that are set out here.

Age, those findings show, is not entirely unrelated to performance. Thus, if one simply takes the population of past presidents and divides it at the median age on inauguration, the average ranking of the presidents in the older group is not significantly different from that of those in the younger group, regardless of whether the post-2000 presidencies are included or excluded.

But there are marked differences at the extremes. In particular, even excluding the most recent presidencies, the five highest-ranked presidents are nearly seven years younger than the five most poorly ranked presidents. Moreover, the difference is sufficiently great that it is very unlikely to be due to chance.

Equally, again excluding the presidencies after 2000, the six youngest presidents – that is, those whose age on inauguration was more than one standard deviation below the mean – have an average ranking 50 per cent better than that of the five presidents whose age was more than one standard deviation above the mean. And that gap too is unlikely to be due to chance.

One might therefore conclude younger presidents perform better. But it is highly questionable whether the differences are in fact due to age. Rather, a person who secures election unusually young is almost certain to be an exceptional candidate, with attributes ranging from boundless determination to palpable charisma.

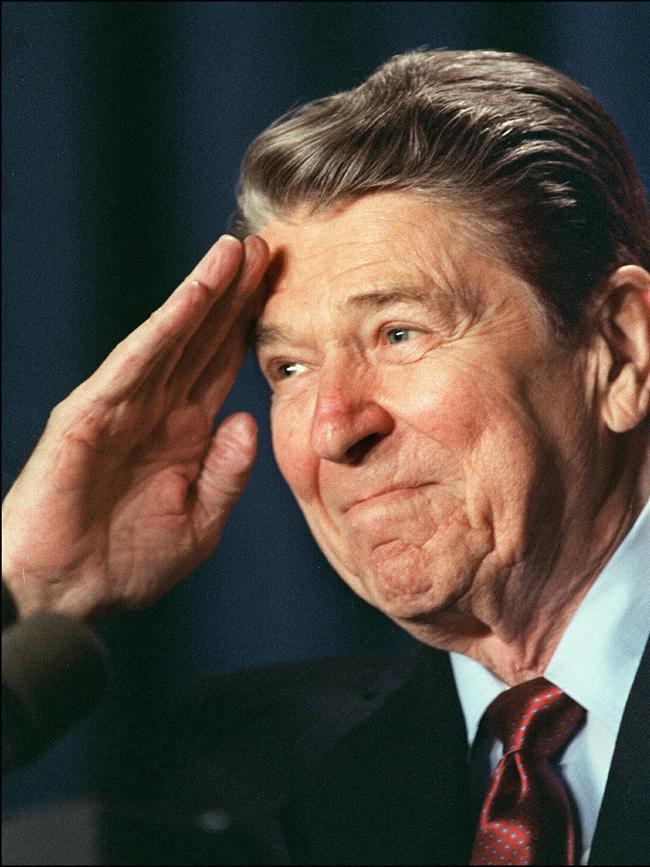

Conversely, several of the oldest presidents, such as James Buchanan, Zachary Taylor and William Henry Harrison, were, much like Joe Biden, quintessential party stalwarts, whose ascent owed more to staying power than to talent. But others, such as Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, were remarkably effective leaders, steering the US through seismic change.

It is, in other words, not age but what used to be called character that is at work. That would scarcely have surprised the Victorians, for whom character was all. Nurtured on the classics, they knew Cicero’s warning that it was not age itself, but the ability to learn from experience, that determined whether the passing years brought wisdom or a detachment from reality.

And it was whether the American political system recognised and rewarded character that the era’s most eminent thinkers asked when they looked across the Atlantic.

This much seemed obvious: most American politicians were, as James Bryce put it in The American Commonwealth (1888), “intellectual pygmies”, elected by voters who “do not object to mediocrity”. The explanation was simple – in a thriving economy, politics was not an attractive vocation.

Nor was that necessarily a weakness, argued the brilliant Irish liberal, William Lecky, in Democracy and Liberty (1896). On the contrary, that the best and brightest “stayed apart from politics” both boosted the nation’s prosperity and created a pool of “great men” who could weigh against the intellectual pygmies.

And even when countervailing pressure was ineffective, the constitution’s separation of powers, and the complex overlay of the House of Representatives and the Senate, caused so much “waste of power by friction” that the mediocre and mendacious were kept in check.

However, the presidency, with its enormous power, was another matter. Yes, a few presidents had proven absolutely outstanding, particularly Abraham Lincoln. But as Walter Bagehot tartly commented in The English Constitution (1867), “success in a lottery is not an argument for lotteries”– least of all when so much is at stake. Whether the position reliably went to “men of admirable character” was consequently crucial.

The “inflexibility” of the American constitution made that even more important. In Britain, prime ministers only lasted for so long as they retained the confidence of their peers. While that scarcely ensured success, it gave some protection against abject failures. It also meant, said Bagehot, that in a crisis, a new leader, better suited to the period’s demands, could be chosen, allowing “the pilot of the storm” to replace “the pilot of the calm”.

In contrast, labouring under rigidly fixed terms, Americans had few options once buyers’ regret set in. That was, from time to time, inevitable: even with candidates who had previously held high office, predicting how well they would deal under ever-changing circumstances was impossible.

John Tyler, Millard Fillmore and Andrew Johnson were, for example, all vice-presidents who rose to power when the elected president died. Yet, said Bryce, “the only thing remarkable about them is that being so commonplace they should have climbed so high”. But once their inadequacy had become manifest, the slow, divisive and generally unworkable process of impeachment was the sole remedy.

No one worried more about the risks that posed than Bryce, who was convinced the US would eventually shape the world. “If the men are not great,” he wrote, observing congress in action, “the interests and the issues are vast and fateful.”

“Here, as so often in America, one thinks rather of the future than of the present.” And while that future was uncertain, the day would surely come when “the parliaments of Europe have shrunk to insignificance”.

Could the United States, which selected its leaders with so little regard to character, be counted on to address the “tremendous struggles” it would then have to face? With an exceptionally ugly presidential battle raging, that question remains as pressing as ever.

“The public favour,” Edward Gibbon noted in discussing the fate of the emperor Constantine, “seldom accompanies old age.” Ever reluctant to acknowledge “the experienced merit of a reigning monarch”, the imagined virtues of a younger successor all too readily aroused in the public mind “the most unbounded hopes of private as well as public felicity”, encouraging a headlong rush toward future disappointment.