A presidential run behind bars? It’s been done before

Note that being a felon and incarcerated for serious crimes was no bar to seeking the presidency, and this remains the case.

Alexis de Tocqueville may have been even more perceptive when he opined that “honourable men do not run for public office in America”. The critics of Donald J. Trump for more than four years have used the expression “the walls are closing in on Trump”.

This may at last be true. Trump faces prosecutions over alleged breaches of state and federal criminal statutes.

The Mar-a-Lago documents matter is serious, as is the impending decision of Special Counsel Jack Smith on the January 6 riot at the US Capitol and Trump’s possible role in it. This is before we get to the state of Georgia and allegations of election interference, or fake electors in Michigan and Arizona. But the reality is, even if convicted and incarcerated, Trump can still run for the presidency in November 2024. It has actually been done.

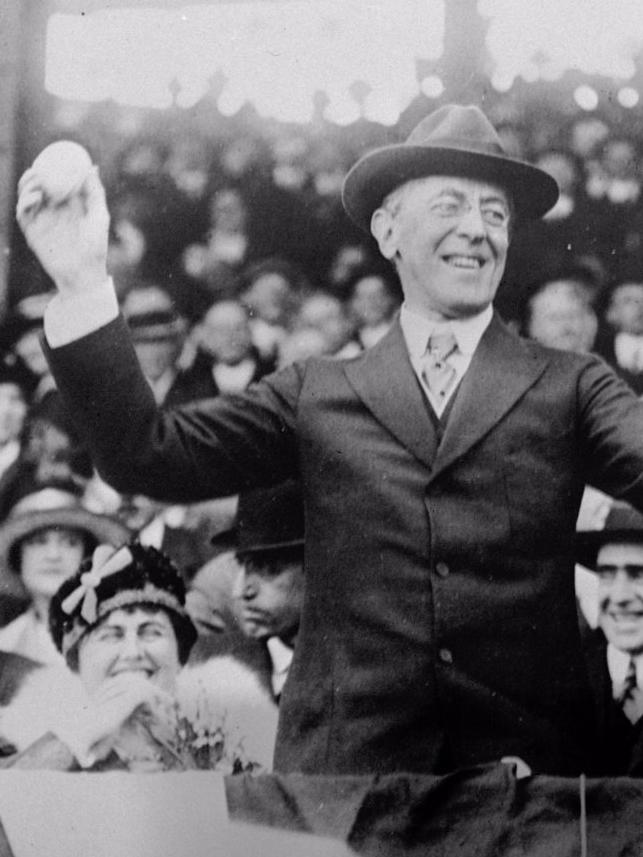

In the 1920 election, the remarkable candidate for the Socialist Party of America, Eugene Victor Debs, ran for the presidency and garnered more than 913,000 votes, about 3.5 per cent of the total vote. Debs emerged from the infant US labour movement and ran for the presidency on five occasions. But his 1920 effort was an astonishing campaign, as it was headquartered out of the Atlanta federal penitentiary.

Debs was a brilliant orator who had proved his value as a leader in the American Railway Union, particularly during the Pullman railway car dispute.

George Mortimer Pullman still represents the definition of greed, slashing his workers’ wages while insisting they pay the same rent for company housing. Pullman’s response to the objections of employees was brutal. He fired them.

Debs was incarcerated for his vocal opposition to America’s entry into the Great War and the “Junkers of Wall Street” who supported it. This enraged Woodrow Wilson. The crimes somehow arose from a speech in Canton, Ohio, home of future president Warren Harding, which was ruled to violate the Sedition Act of 1918, an amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917. On November 18, 1918, a week after Armistice Day, Debs was condemned to three concurrent 10-year prison terms. The draconian sentence was upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court in 1919.

In prison, Debs sought no special treatment, sharing a cell with five others for 14 hours a day. He placed an image of Jesus Christ bearing the crown of thorns on the wall. Years after Debs was released, Sonny Liston, who went on to be the boxing heavyweight champion of the world, honed his fighting skills in bouts in the penitentiary. When the election of November 1920 rolled around, Debs declared himself a “candidate in seclusion”, with campaign buttons emblazoned “Prisoner 9653 for President”.

This was a unique strategy.

Trump, if convicted, is unlikely to be incarcerated in a federal penitentiary as “hard time” as Atlanta was in 1920. Trump would be unlikely to join “Traitors Row” in the federal “supermax” facility in Florence, Colorado, but could perhaps be more expected to enter a “Club Fed”, similar to the facility in Lompoc, California. This is possibly before us, but the surprising reality is that a felon can not only run for office but could presumably endeavour to govern from prison.

Trump has always sought to portray himself as a victim at the mercy of the “Deep State”. He craves martyrdom. A spell in a federal penitentiary might be more than he bargained on, but incarceration as a result of the prosecutions against him cannot be dismissed.

Debs was a singular American. His parents were said to have named him for Eugene O’Neill and Victor Hugo, thus confirming their ideological leanings. Debs lived up to his parents’ expectations, emerging as one of the founding figures of the Industrial Workers of the World (“The Wobblies”), who achieved status as radical labour organisers at the turn of the 20th century.

Wilson may have despised Debs, but Warren Harding took a more sanguine view of the labour leader’s future contribution to America, commuting his sentence and inviting him to the White House in December 1921. There is no record of what was discussed at the White House meeting between the president and Debs, but Harding’s Republican generosity stands in marked contrast to the vindictiveness of his Democratic predecessor.

Gerald Ford showed excellent judgment in 1974 in pardoning former president Richard Nixon over the Watergate scandal and drawing a line under that tortured period in US politics. As senator Ted Kennedy observed years later, he had been a critic of the president’s decision, but the president was right, and he, Kennedy, was wrong. Joe Biden may be moved to demonstrate similar magnanimity.

The Trump campaign seems to be driven by a desire for Trump to win the White House and pardon himself. Fine, for federal crimes. However, presidential power in state courts is far more a moot point.

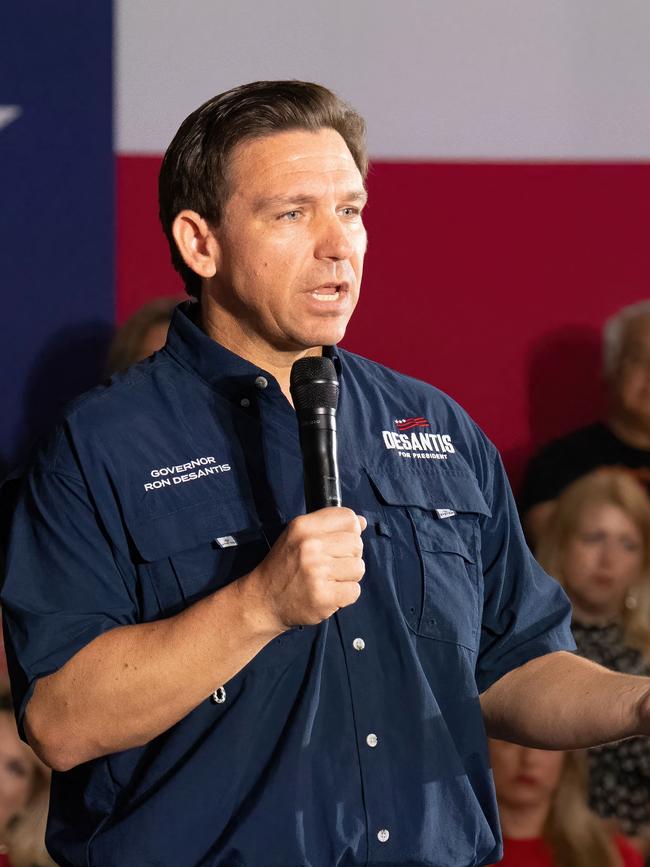

Almost certainly, given Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s failing and faltering campaign, and the devotion of the Trumpanzee base of the party, Trump will win the Republican nomination again. But it is doubtful if he can win the presidency. His legal challenges are real and are growing. It may well be “Club Fed” that welcomes him to his next residence rather than 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington DC. Debs would believe that this made his campaign worthwhile.

Stephen Loosley is a non-resident senior fellow at the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Article 2, Section 1, Clause 5 of the US constitution sets the requirements to be elected president: “No person except a natural-born citizen, or a citizen of the US, at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall be eligible to the office of president; neither shall any person be eligible to that office who shall not have attained to the age of thirty-five years, and been fourteen years a resident within the United States.”