A decisive win on the long road to referendum

The referendum will be Labor’s first attempt to change the Constitution since 1988, and the nation’s first referendum since John Howard put the republic to a vote in 1999. As the emotion of the press conference demonstrated, there is a lot riding on this poll. For good or ill, the vote will be a turning point in the nation’s relationship with its first peoples.

Albanese confirmed his wording for the voice after months of consultation with Indigenous people and with the benefit of advice from a constitutional expert group (of which I am a member). The process confirmed the government got it largely right when Albanese announced draft wording for the voice at Garma in July.

Labor has stuck to its simple and direct three-sentence change to the Constitution. This establishes there will be an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice. The body will have the power to make representations to parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Parliament will have a say over the work of the voice by making laws for its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

Albanese on Thursday announced three significant tweaks to his Garma wording. Each represents a worthwhile improvement. First, the text of the Constitution setting out the voice will be prefaced by new words making clear the change is “In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia”. This is an important addition that makes clear why the Constitution is being changed. The voice is an act of recognition to ensure Indigenous peoples are included in the nation’s founding document and to affirm their status as the first peoples of Australia. These words are powerful in tying the referendum proposal to the concept of recognition, which has been an animating idea in the reconciliation and constitutional change movement for more than two decades.

Second, the wording clarifies that the voice can make representations to parliament and the executive government “of the commonwealth”. This limits the work of the voice to these national institutions, while leaving parliament able to increase the remit of the voice to other bodies and tiers of government. Any extension would be a matter for the people’s elected representatives and is not something the voice itself could initiate.

The result is a more limited scope for the voice respectful of the nation’s federal structure and the fact that other parts of the nation, most prominently South Australia, are forging their own path.

Third, the new wording adds a little bit of lawyers’ language to the power of parliament to make laws for the voice. The original wording made clear parliament could legislate for the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the voice. Albanese’s new wording retains this, while also removing the fetters on parliament by authorising it to make laws generally “with respect to matters relating to” the voice.

This broadens out the scope for Parliament to control and shape the operation of the voice without being constrained to its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

These words reflect how the government and its Indigenous working group have resolved differences over the possibility that decisions by the executive might be challenged if they fail to account for representations by the voice. The new wording will permit parliament to make laws about a broader range of matters, including if it wishes to restrict the possibility for judicial review if, for example, a minister or public servant fails to listen to what the voice has to say. The change is an assertion of parliamentary sovereignty and is an elegant, if legalistic solution to what had become a prominent political problem. Labor will introduce its revised wording into parliament next week. This is much more than a formality.

No referendum can be put to the people without the blessing of parliament. This ensures that any change to the Constitution has the support of our elected representatives and is subject to robust and public deliberation.

The parliamentary process may yet have a decisive say on what is put to the people. There is precedent for this. In 1946 Australia went to the polls to change the Constitution to permit the federal parliament to provide social services to the community including widows’ pensions, unemployment benefits, and medical and dental services.

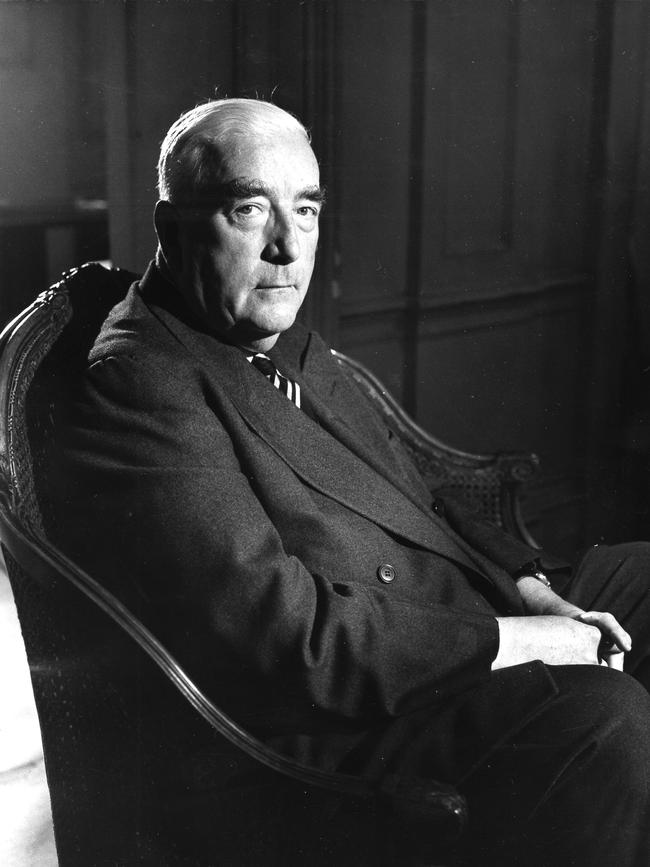

The proposal was championed by the Chifley Labor government but met opposition from Robert Menzies as leader of the Liberal Party. Menzies pressed an amendment that qualified parliament’s new power by making clear medical and dental services could not “authorise civil conscription”. Labor accepted the change, and its constitutional reform passed the House of Representatives. Soon after, the people endorsed the change at a referendum.

The 1946 referendum remains Labor’s solitary success in changing the Constitution. Its other 24 attempts, none of which attracted bipartisan support, failed. Even then, success in 1946 was hard-won. The proposal achieved a Yes vote of 54.4 per cent, the lowest Yes vote for any of Australia’s eight successful referendums. That experience demonstrates there is still a long road ahead, full of potential twists and turns, before the people vote in this referendum.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.

Anthony Albanese’s announcement of his government’s preferred wording for the voice is a historic moment.