Where in the world would you rather be?

Let’s take a big dataset of economic and demographic characteristics of all 216 countries and territories that the United Nations officially recognises, and see where people and capital might want to call home.

We would probably want our country of choice to experience population growth. Declining nations have ageing populations, shrinking markets, and face serious structural challenges that can lead to political unrest. We want our country to be relatively highly developed and eliminate all nations that have a lower developmental standard than Samoa (0.7 on the Human Development Index).

A certain level of democratic freedom would be nice. Let’s pick nations that score at least a 6 on the Democracy Index. That means we want to live in a place that is more democratic than Bangladesh. Countries like Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka rank just above 6, whereas Australia, Canada, and Germany are ranked at about 8.7. The most democratic country in the world, Norway, scores an impressive 9.8 on the Democracy Index.

In our country of choice, we also want to enjoy a basic level of economic prosperity. If an economy is too small, our opportunities are severely limited. How big is big enough? Hard to say. I think a country’s economy should be at least as big as the economy of the Gold Coast. Let’s delete all countries with a GDP smaller than $US30bn ($46.4bn).

We want to ensure that we get a fair share of the economic pie in our country of choice. GDP per capita is a good enough proxy for this quick estimate. We want to be richer than the average Panamanian and set our filter to $US20,000 ($30,940) per capita.

Do we want our country to be of a specific size? Similar to the size of the economy, a certain level of population size is needed to ensure that we find enough people that share our interests, that niche markets are sizeable enough, that we find a decent variety of cuisines and cultures. We should stay on the conservative side and only delete countries with a population below 1.4 million people – a country should at least be the size of Adelaide, right?

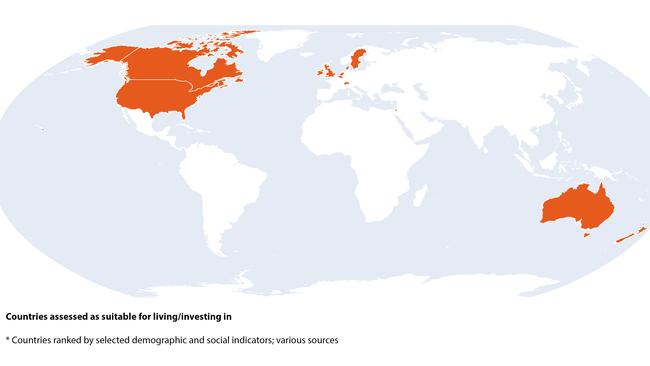

After applying these six simple filters, only 15 out of 216 nations are left: US, France, UK, Canada, Australia, The Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Israel, Switzerland, Denmark, Singapore, Norway, New Zealand and Ireland.

In addition to these filters, we might want to add scenarios regarding climate change, global trade interruptions, and geopolitical stability. Moving to or investing in Israel right now, for example, isn’t for the faint-hearted. Many commentators expect a global increase in unmanaged population flows as a result of climate change and geopolitical disruptions. As areas become inhabitable or economically unproductive, people are forced to move. As wars rage, large population are displaced, and as youth unemployment is high in the poorest and biggest nations, young people cross borders in search for a better life. The unmanaged population flows across the Mediterranean Sea over the last decade were likely just the beginning of an ongoing trend. European nations will continue to deal with the aftermath. All European countries remaining on our map should be viewed in a broader context. Europe is ageing, faces migration challenges, has the potential for a Russian-induced wider conflict, suffers from rising energy costs, and must urgently reinvent their business model.

In Australia we remain geographically isolated and can continue to manage our population flows – a rare privilege.

Now that we agree that Australia is a great place to live and invest in right now, let’s explore if we should look optimistically into the future too.

Is our national business model at risk? Will we still be a prosperous and wonderful nation in the coming decades?

Australia operates a comically simplistic economy. The Atlas of Economic Complexity, produced by the Growth Lab at Harvard University, measures (you guessed it) the complexity of economies around the world. The researchers analysed 133 countries and placed Australia at an embarrassing rank of 93. This makes our economy less economically complex than Uganda on rank 92. In the 2000 version of this ranking, Australia sat significantly higher (rank 60) – we have made our economy less complex by closing our car manufacturing. for example.

Today, in Australia we create wealth by doing four things and four things only that matter to the rest of the world: mining, agriculture, international education, and tourism. That’s it. That’s all we export. That’s how we achieve a positive trade balance and bring foreign capital into our country. Of our 25 largest exports, 21 fall into these four sectors while the remaining four largely link back to these four sectors indirectly (we export services regarding professional services, intellectual property, technical advice, and financial advice).

Geopolitically, we also matter by allowing the US to park a bit of their military equipment on our shores – but that’s not overly important economically.

Our heavy reliance on resource extraction is the reason why many commentators argue that Australia runs a third world economy.

While our business model isn’t overly complex, it’s almost certainly continuing to deliver prosperity and population growth – two important factors for the wider property industry.

All four industries that make Australia successful require local workers.

This means we can’t follow the Japanese model as our population ages rapidly. Japan has been shrinking its population base for more than 30 years and still managed to increase GDP.

Australia can’t follow Japan’s lead because our business models are fundamentally different.

Japan can grow its economy because Toyota, Mitsubishi, Honda, Sony, Nissan, Canon, and Fujitsu run factories across the globe, utilising workers outside of Japan to produce their products. Such hi-tech manufacturing also lends itself to heavy robotisation. Japanese banking, insurance, and IT businesses are scalable with relatively little input of labour. Japanese businesses don’t rely nearly as much on their local workforce as Australian businesses do.

Our Australian mining and agriculture businesses need people on the ground drilling and harvesting. These jobs can’t possibly be done outside of Australia. Obviously, these sectors will heavily invest in robots and AI to tackle the prolonged skills shortage.

Tourism also takes place exclusively in the country and necessitates a large local workforce. International education could theoretically be scalable through online programs and overseas campuses, but for now, all the money worth speaking of is created on Australian soil.

For the Australian business model to work, we need local workers. A low migration scenario in Australia would necessitate a complete overhaul of our national business model. I don’t think that is likely at all. I would therefore argue that, looking 10–40 years into the future, the only plausible migration scenario for Australia is a high one.

If Australia was to slow down it’s migration intake, it would need to come up with huge tax reforms.

More than half of the tax that the Australian Taxation Office collects is from income tax. Will any treasurer allow their prime minister to shrink the pool of taxpayers in a decade in which the big baby boomer cohort will stop paying income tax as they retire? Do you see either of the major parties willing to radically transform the tax system?

On top of this, we face a skills shortage spanning all industries. Cutting migration would make this skills shortage worse. What about housing affordability? Wouldn’t that improve if we were to cut migration?

It’s certainly a line popular with politicians seeking to be elected. It’s not necessarily true, though. During the pandemic years, house prices increased at record speed despite negative migration. Low interest rates helped the housing market, but we must remember that individual sellers as well as developers time when they put product to market. Cutting migration would have a minimal impact on house prices, at best, while worsening the skills shortage and minimising tax income significantly.

As always, I am happy to be proven wrong but continuing with our existing economic playbook is much more likely than a shift away from our successful national business model, our way of collecting tax, and our high migration approach.

High migration obviously comes with big challenges. Most importantly, we need to grow our housing stock and infrastructure accordingly, we must integrate new migrants into our social fabric, and we must do all this in an environmentally sound way.

At least we know the challenges well in advance and can prepare to ensure we will continue to be a prosperous nation.

Simon Kuestenmacher is co-founder and director of research at The Demographics Group.

High interest rates, a housing affordability and supply crisis, a general cost-of-living crisis, a prolonged skills shortage, geopolitical instability – you’d be excused feeling a bit pessimistic about our country right now. But, once we zoom out and view Australia in a global context, we realise quickly that our pessimism is largely misplaced.