So, why is neither of the two big parties making housing policies for young people?

Housing affordability is best measured by dividing the median price of a dwelling by the median income. To make housing more affordable, you have two options. Either wages grow faster than house prices, or house prices go down. While wages have consistently been going up, they rose much slower than house prices. Is it possible to make housing cheaper?

The final sales price of a home is made up of land value (location, lot size, and infrastructure availability feature here), construction costs (labour, material, architectural design), market conditions (supply v demand, interest rates, investor activity), developer margins, lots of little hidden expenses (agents, banks, inspectors, surveyors all charge fees), and of course taxes (stamp duty, land taxes, infrastructure charges).

Over the last decade, as the price of land continued to grow, we reacted by buying smaller lots. That trend will continue unless we decide to build whole new cities on land that we essentially give away for free.

Constructing a house has become more expensive rather than cheaper. This is partially because we build better homes now and partially because of a failure of the construction industry to innovate and establish faster, less labour-intensive, more automated, less wasteful building methods using cheaper material.

I am cautiously optimistic that we can drive construction costs down as all big players experiment with AI, automation, and modern methods of construction. But just how much prices could be pushed down remains to be seen. Market conditions have favoured high house prices as we saw lots of population growth, while low interest rates pushed people who might struggle to repay their mortgage into home ownership, and as property was made much more attractive to investors than stocks.

Developer margins are always going to be part of the equation. The only way to build housing without these margins would be to introduce a state-owned property developer. If Anthony Albanese, who grew up in commission housing, doesn’t introduce such a developer, nobody else will either.

Agents, banks, and everyone else in the property universe will also need to charge some sort of fee. This leaves taxes as a tool to lower the cost of a home. Unfortunately for all the young aspiring homeowners, governments have been helplessly addicted to property-related taxes.

The Victorian state government last week slashed stamp duty for all off-the-plan units, townhouses and apartments under a 12-month stimulus plan. If this policy can attract sufficient developers to build these new homes, other states will likely follow suit next year. Sooner or later, you must collect another tax if you stop collecting stamp duty though.

Australia, due to its ageing population, is in the need of a much broader tax reform anyway. To quote from the Intergenerational Report 2023: “taxpayers have declined as a share of the total population since peaking in 2005-06”. The way things are going currently, a smaller proportion of the population will have to pay a larger proportion of the tax revenue.

We rely heavily on income tax collected from workers to pay for our public services. Already more than half of our tax revenue comes from income tax. We are set to lose fuel excise income as we continue to electrify our transport system and tobacco excise income as we live healthier lives. Our workforce shrinks rapidly in the coming decade as the whole baby boomer generation moves into retirement.

If you don’t see a massive transformation of the tax system, a likely option, don’t expect any prime minister in the coming decades to follow through on their pre-election promise to cut the annual migration intake – their treasurer simply won’t allow it as money must come from somewhere.

As we further increase our reliance on income tax to finance Australia, high house prices lose their function as a helpful tool to guarantee a sense of financial success. For a while, Australians weren’t too annoyed by tax bracket creep and happily paid more tax since wealth gains through property ownership were so big.

Unfortunately, property wealth isn’t doing anything useful like increasing national productivity or global competitiveness. Had housing investments gone to the stock market, this could’ve helped to grow our economy. Losing the baby boomers’ income tax dollars will be a serious problem in the coming decade and bad news for the remaining workers.

These remaining workers, especially if they are young renters and don’t benefit from rising house prices, increasingly feel the whole system isn’t working for them anymore and turn their backs on the two major parties. Young people feel the Australian property market and politicians are actively working against them. The demographics of politics suggest their assumptions are correct.

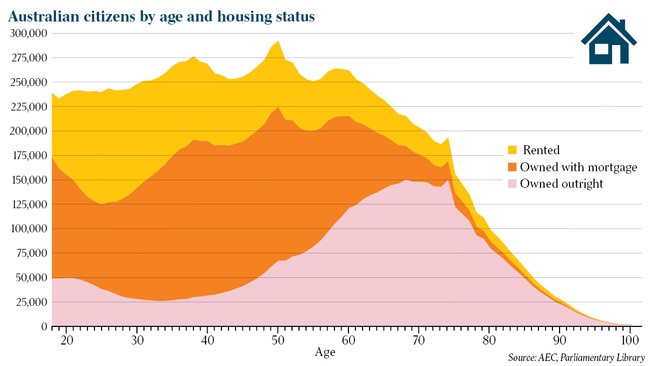

Let’s be cynical for a second and think through who a self-interested politician might be making policies for. Only citizens aged 18-plus can vote them into power. This means only 64 per cent of the population needs to be taken into consideration when making policy, since non-citizens and people aged under 18 don’t matter.

Now let’s look at the housing situation of the 64 per cent of the nation that vote.

Renters make up the minority of the voting public (26 per cent). They can’t however be ignored by politicians – a bit of lip service is still needed. Politicians therefore introduce policies that sound like they might address housing affordability but do the exact opposite.

You won’t find a single economist to support the claim that first homebuyer grants or super for housing makes housing more affordable. These policies drive up house prices and are ultimately bad for first homebuyers and renters.

The majority of voters are mortgage holders (40 per cent) or own their home outright (34 per cent) and won’t support policies that make housing cheaper.

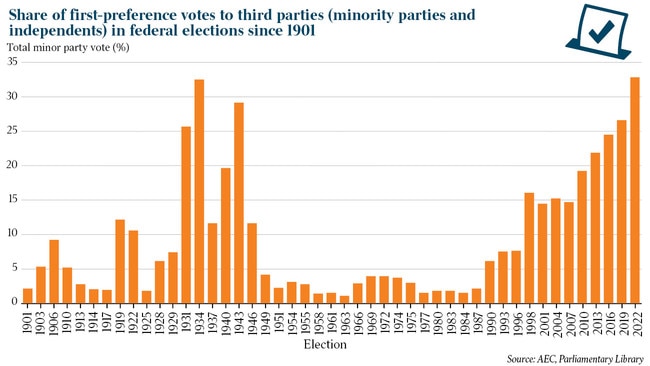

The Australian Election Study shows that young voters have the most negative views towards government; hold the most negative sentiments towards politicians; and vote increasingly for third parties. In 2022, almost a third of all first-preference votes went to parties other than LNP or ALP. Since the 1987 election, third party votes have only increased. I would argue that each election in the coming two decades is all but guaranteed to see a slightly higher share of votes going to third parties.

At the last election, the winning ALP secured less than 33 per cent of all votes. The 4.7 million Australians voting for the ALP made up a mere 18 per cent of the total Australian population at the time.

We will soon see elections where the new prime minister, in his victory speech, still thanks the Australian people for the strong mandate to push their policy agenda despite securing less than 30 per cent of all votes or less than 15 per cent of the Australian population.

This isn’t a critique of our preferential voting system but a simple forecast that the governing party increasingly will need to bend to the will of minor parties to get anything done. The Greens have already showed their unwillingness to compromise on housing policy. This tough approach to policy will be the norm.

Ultimately, house prices must come down to attract young voters back to the major parties and reduce the fragmentation of government, which will only make policy decisions harder to enact.

Simon Kuestenmacher is a director and co-founder of The Demographics Group.

Many young people have completely given up hope that they will ever be able to afford a home. House prices have risen much faster than wages, and even renting is stupendously unaffordable. For young people, it’s very easy to be cynical about their future property prospects.